Back to selection

Back to selection

The Blue Velvet Project

Blue Velvet, 47 seconds at a time by Nicholas Rombes

The Blue Velvet Project, #131

Second #6157, 102:37

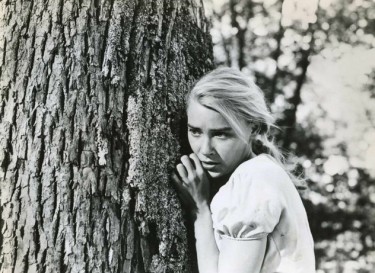

“Mom . . . is Dad home?” Sandy asks. If Blue Velvet were a comedy (and it approaches one at moments like this) there might be canned laughter following this line. After all, Sandy has just entered the house with the local nightclub singer, naked, bruised, and clinging to Sandy’s new boyfriend Jeffrey.

Jeffrey in the realm of women: Dorothy (the bad one), Sandy (the good one), and Mrs. Williams (the dutiful wife and mother). What we’re looking at here is pure, raw, sex, unrestrained by custom, duty, or conventional notions of morality. Sandy knows it; it shows in the thrill that registers in her splayed fingers. Mrs. Williams knows it too, and wants to cover it up. (“I’ll get a coat to put on her,” she’ll say in a few moments.) She is played by Hope Lange, whose portrayal in Peyton Place (1957) of Selena Cross, who is raped by her stepfather, creates a weird echo in Blue Velvet, which in many ways is an updated version of Peyton Place.

For both Peyton Place and Blue Velvet are about small towns pulled apart not by some outside force but from the internal lapsing of the codes and signals of repression. In this frame at second #6157, Hope Lange’s appearance as the calm matriarch puts her fully on the side of the Law: her calm demeanor suggests that Order soon will be restored.

And in some respects, Order is restored more firmly and completely in Reagan-era Blue Velvet than in Eisenhower-era Peyton Place. While no film can ever seal completely the ideological gaps it opens, Blue Velvet seals them as tightly as possible, with the destruction of Frank, the partial restoration of Dorothy’s life (who fully assumes the role of a mother by the film’s end), and the implied re-balancing, normalization, and continuation of the romance between Jeffrey and Sandy. And yet, while the sordid disruptions in Peyton Place were coded as sociological (“caused” by conditions that could be understood) the evil of Frank in Blue Velvet transcends rational explanation. It’s not so much that Order is restored at the end of Blue Velvet, but that its destruction proved so easy, and so outside the control of human agency. In this sense, Blue Velvet is a fantasy.

Over the period of one full year — three days per week — The Blue Velvet Project will seize a frame every 47 seconds of David Lynch’s classic to explore. These posts will run until second 7,200 in August 2012. For a complete archive of the project, click here. And here is the introduction to the project.