Back to selection

Back to selection

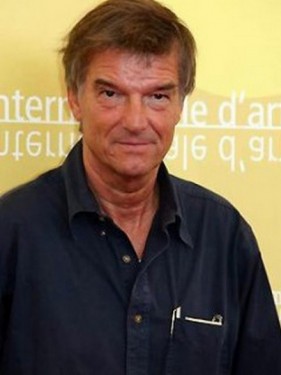

Benoit Jacquot, Farewell, My Queen

The court intrigue that animates Benoit Jacquot’s Farewell, My Queen — set during the final days of Marie Antoinette’s reign — could be the stuff of so many costume dramas. To his great credit, however, the 65-year-old Parisian director, best known on this side of the pond for his 1995 hotel chamber drama A Single Girl, offers an elliptical, accumulative account of the events, keeping them tightly focused on the experience of the Queen’s private reader Sidonie (Léa Seydoux) as the storm clouds of revolution gather from outside the corridors of Versailles and the regime’s demise very quickly becomes inevitable, even as the insufferable queen (Diana Kruger) manages to lack any understanding of why her subjects are bent on her untimely exit.

As revolution marches toward them, Sidonie’s infatuation with the Queen is marked by jealousy at her attachment to the cosmopolitan duchess Gabrielle de Polignac (Virginie Ledoyen, who Jacquot made a star in A Single Girl). Servants and courtiers begin to realize that no one is safe and hushed panic spreads throughout Versailles, all while the film savvily maintains an emotional coolness towards its protagonist. Seydoux’s servant girl begins to use her access to the queen to her advantage in ways that the film refuses to render judgement on despite their moral dubiousness; ultimately, they throw into relief the matrix of class and power that so defines the political machinations of the age.

In this way, Farewell, My Queen, which was the opening night film at this year’s Berlinale, proves to be an effective remedy against Sofia Coppola’s confounding Marie Antoinette. Shot in a somewhat loose, naturalistic manner by Romain Winding, the film effectively dirties up the opulent surroundings, grimly focusing on both the story of one woman’s attempt at surviving the tides of history and the complicated ways in which power leaves some people clueless. Adapting Chantal Thomas’ novel with Gilles Taurant, Jacquot renders the whole thing with an immediacy that those familiar with his eclectic filmography would recognize, from his 1977 Nouvelle Vague-inspired Les enfants du placard to Écrire and The Death of a Young English Aviator (both 1993), his wide-ranging documentaries about French author and filmmaker Marguerite Duras.

Farewell, My Queen opens Friday in Manhattan.

Filmmaker: Had you wanted to make a film set in this period for some time? Or did Thomas’ novel spark your interest?

Jacquot: No, it was the novel. I read it quite by chance actually, but it is what gave me the desire to make this film. It’s not specifically, exactly the novel, but the whole way the novel is constructed, and structured. I thought that perhaps I could make a film doing something similar.

Filmmaker: Was there something about the court of Versailles, about the way Marie Antoinette and her subjects lived, that you particularly wanted to dramatize after that initial reading of the book.

Jacquot: Generally speaking, I’m very interested in showing what you might call the back side of the decorum. Here what interested me was showing the Court of Versailles, which was extremely opulent, with its gallery of mirrors and so forth, and to contrast that with what was going on behind the scenes, behind closed doors, away from where the king and queen were, inside people’s little apartments. I wanted to know what goes on behind the set of the typical film about these matters, in the other places.

Filmmaker: How did you try to differentiate this film from other films about the period, and about Antoinette specifically, from an aesthetic point of view?

Jacquot: I’m not necessarily trying to single my film out from all the other films made about this time period, but I would say that what I tried to do with my film was avoid anything that screamed, “recreation.” Given how [it’s a] narrative period film, of course it’s a recreation because it’s not actually taking place in the same time period, but I really wanted to avoid the antique look and feel and to make the audience feel as if they were experiencing everything with the characters for the first time and the last time.

Filmmaker: The style seems to grown more rough hewn as the weekend grinds on and the tentacles of revolution begin to wrap themselves around the palace.

Jacquot: One of my principles in directing this film was to show the gradual breaking down of what was a very regulated and regimented hierarchical system which was life at the court. Everyone obeyed the structure, acted accordingly to the structure, obeyed a certain kind of protocol. As news begins to come in from the outside, it begins to come apart, slowly. I think the way we shot the film reflects that as much as what happens in the film.

Beginning with the central principle of the film, to follow all of the events and everything that takes place from the perspective of this single character, the young reader, and as panic spreads as news of what’s going on outside begins to filter throughout the palace, life there begins to change rapidly and she is very much a part of that life so as she begins to be affected by everything that is going on all around her, the camera too begins to be affected, begins to indicate her increasing tension, the madness that is setting in. The camera begins to follow her in a way that can be viewed as it being an extension of her physicality, of her nervous system, because it is her perspective and it is seen from her point of view. The camera is an extension of what she is experiencing in this Court that she is so integral a part of.

Filmmaker: Does this film contain any preoccupations of yours that one can glimpse in your other work? Is there a window through which one could see Farewell, My Queen as being of a piece with, say, A Single Girl or À tout de suite?

Jacquot: If you take a look at my films, even though they are very different, you can look at them and recognize that they were in fact made by the same person, but to say exactly what the link is might be rather difficult. I think that in each of my films there is a secret that must be protected by someone who is quite vulnerable. I don’t know if that’s what drew me to this book, but it is in there as well.

Filmmaker: Where, if at all, did you depart significantly from Thomas’ text?

Jacquot: There are two basic places where there is a real departure. Both were made with the approval of Chantal Thomas, the author of the novel upon which the film is based. First is the age of the main character, the reader. In the book, she’s actually a woman who’s about 50 years old. In the film, she’s a young woman who is about 20. She is mature, but she is still very young. The second is that the novel is told almost as a retrospective on this woman’s life, in flashback, looking back at what she had done. I wanted to tell my film in the present tense.

Filmmaker: Was there any aspect of the story that you reimagined or significantly reworked while you were making the film, or in postproduction?

Jacquot: Actually, most of my films end up looking the way I originally imagined they would. Naturally there are things that crop up that end up not fitting in and I just dispense with them as I go along, during production and during editing. In this case, I cut out about 20 minutes of the film. The first cut of the film was about two hours, but the cut that everyone will see in the cinema lasts about an hour and 40 minutes. It really does show that there is a difference between what I imagined the film would be and what it ultimately ended up being, and I can’t say that I’m ever really conscious of how the process is going to work each time. For instance, in this case, I didn’t know what the ending of the film would be while we were shooting. It was only during the editing that I decided that it would end with Sidonie’s voice over.