Back to selection

Back to selection

The Blue Velvet Project

Blue Velvet, 47 seconds at a time by Nicholas Rombes

The Blue Velvet Project, #138

Second #6486, 108:06

Inside Dorothy’s apartment Jeffrey surveys the carnage. The television set, its screen cracked. Detective Gordon, the Man in Yellow, somewhere in between dead and alive, and perhaps, at the outer edges of possibility, hooked up to the television. Lynch has talked about his desire to make a painting that “would really be able to move” as a motivation for making his first films, and during the apartment scene the screen does indeed become like a canvas, its objects staged and still, with occasional movement, some fevered dream of an automated wax-museum.

Is Blue Velvet an avant-garde film? Was it ever?

In his classic study Avant-Garde Film: Motion Studies (1993) Scott MacDonald wrote that

The mainstream cinema (and its sibling television) is so fundamental a part of our public and private experiences, that even when filmmakers produce and exhibit alternative cinematic forms, the dominant cinema is implied by the alternatives. If one considers what has come to be called avant-garde film from the point of view of the audience, one confronts an obvious face. No one—or certainly, almost no one—sees avant-garde films without first having seen mass-market commercial films. In fact, by the time most people see their first avant-garde film, they have already seen hundreds of films in commercial theaters and on television, and their sense of what a movie is has been almost indelibly imprinted in their conscious and unconscious minds.

Rather than mutually exclusive, mainstream cinema and avant-garde cinema are, and seem always to have been, dependent on each other. As MacDonald suggests, even in alternative cinema—in films that break all sorts of conventions—the dominant cinema (whatever that may be in any given era) is implied by the very breaking of these rules. Blue Velvet pushes at the outer edges of mainstream cinema not in any overt technical or stylistic way, nor in the ways in which it was financed or produced, and it is certainly not a part of any self-conscious movement. Instead, there is something about the elusive way that the camera inhabits the film’s spaces. Part of it has to do with the duration of the shots, which often last for several beats longer than we expect them to. And the sound during these shots (there’s almost always sound in Blue Velvet, even if it’s just a faint, deep growl, as if the characters are separated from the hell beneath them by nothing more than an unsteady membrane) is so much a part of the disorienting quality of the film, creating a sort of depth of field that takes us, somehow, through the screen and into the film itself.

Blue Velvet was of that generation of films released during the rapid ascendency of home video, and this has something to do with its fluidity as both an avant-garde and mainstream film. According to Frederick Wasser in Veni, Vidi, Video: The Hollywood Empire and the VCR, by 1987 (the year Blue Velvet was released on VHS in the U.S.) VCRs as a percentage of U.S. TV households was around 52%, as compared to only 3% in 1980.

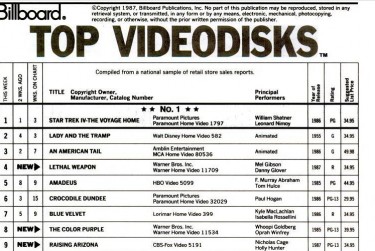

In a 1987 issue of Billboard, Blue Velvet is listed as one of the top videodisk sellers, up there with Lady and the Tramp and Lethal Weapon. Taken together, the nine films listed above make up an unexpected, perhaps even Lynchian, playlist.

Over the period of one full year — three days per week — The Blue Velvet Project will seize a frame every 47 seconds of David Lynch’s classic to explore. These posts will run until second 7,200 in August 2012. For a complete archive of the project, click here. And here is the introduction to the project.