Back to selection

Back to selection

The Blue Velvet Project

Blue Velvet, 47 seconds at a time by Nicholas Rombes

The Blue Velvet Project, #142

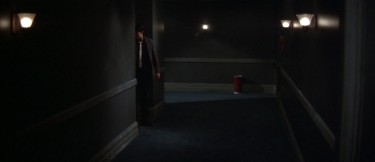

Second #6674, 111:14

The seemingly insignificant, glimpsed, unremembered moments of a film revealed in the details of a random frame. In this case, Jeffrey’s watch, fleetingly illuminated as he retraces his steps back up to Dorothy’s apartment, in flight from the Well-Dressed Man. The importance of the watch may be the very fact of its unimportance—it has no significance in terms of the plot. And yet, it is a part of the film; it constitutes an element of Blue Velvet’s image-archive.

The frames come from a compressed sequence made up of 17 shots that, in less than a minute of screen time, depict a revolution in Jeffrey’s thinking. Rather than leaving the nightmare behind, he returns to Dorothy’s apartment to confront it. The images below are the lead frames from each of the 17 shots, offering a slowed-down glimpse of Blue Velvet‘s narrative speed at this point. In “An Aesthetic of Reality,” André Bazin—who favored the long take and deep focus as opposed to editing or montage as cinematic tools to capture the magic of reality—praised such techniques in Citizen Kane:

Orson Welles restored to cinematographic illusion a fundamental quality of reality — its continuity. Classical editing, deriving from Griffith, separated reality into successive shots which were just a series of either logical or subjective points of view of an event. . . . The construction thus introduces an obviously abstract element into reality. Because we are so used to such abstractions, we no longer sense them.

And yet, we remember films—which are after all are not representations of reality but rather instances of reality itself—differently from how we experience them at the moment of watching them. The act of memory transforms them, so that we may, for instance, recall the arrival of the Well-Dressed Man in Blue Velvet as constituting four or five shots rather than 17. Bazin’s insight that “we no longer sense” successive shots because we have grown accustomed to the fact that cinema uses these to convey the flow of time and reality remains as radical and disarming today as it did in 1948, when the possibility of a feature-length film with no cuts (such as Russian Ark) remained outside the reach of technology.

And so: 17 shots, happily misremembered:

Over the period of one full year — three days per week — The Blue Velvet Project will seize a frame every 47 seconds of David Lynch’s classic to explore. These posts will run until second 7,200 in August 2012. For a complete archive of the project, click here. And here is the introduction to the project.