Back to selection

Back to selection

Angela Davis on Free Angela Davis and All Political Prisoners

Angela Davis

Angela Davis “When the doors slid open, furious flashes of light jolted me out of my reflections. That’s why they had cuffed by hands in front. As far as I could see, reporters and photographers were crowded into the lobby. Trying hard not to look surprised, I lifted my head, straightened my back and between the two agents, made the long walk through the light flashes and staccato questions toward the caravan waiting outside.”

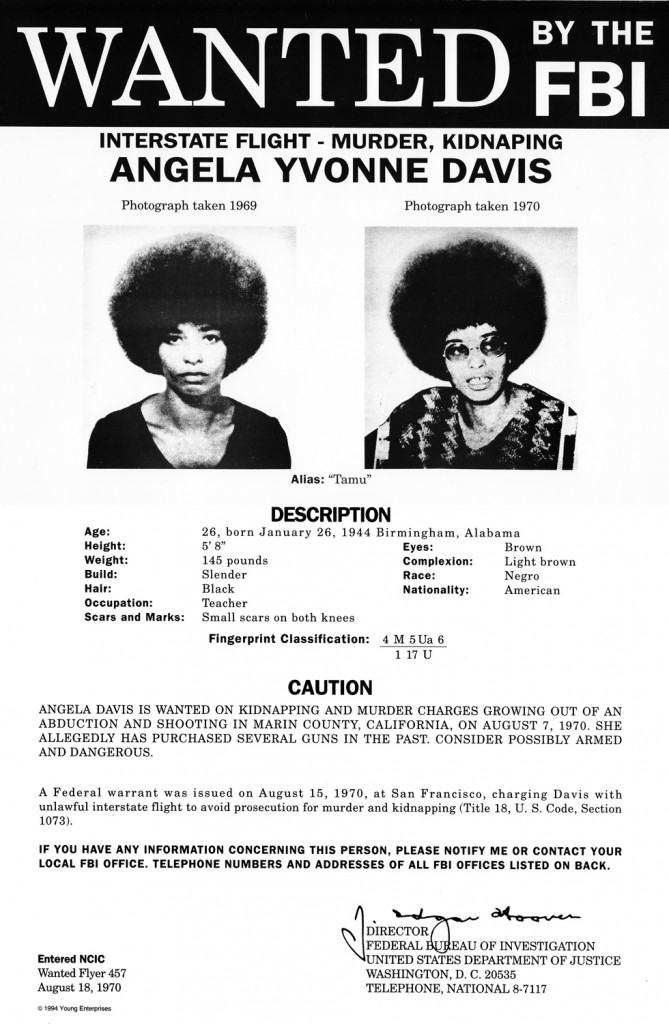

These lines from Angela Davis’s 1974 autobiography, written at the age of 28 and edited by Toni Morrison, describe the way she remembers a humiliating perp walk four years before. At the time, Davis was among the FBI’s Most Wanted. She had been fired from her UCLA professorship for being a Communist. She had spent the last three months living underground. She faced charges of murder, kidnapping and conspiracy. Yet Davis’s instinct, in this situation, was not to assume the traditional position of a fugitive in handcuffs, cowering, hiding her face. Instead, she tried hard not to look surprised. Lifted her head. Straightened her back. She stood tall.

Remarkable poise and dignity are among the characteristics that Free Angela and All Political Prisoners, the new documentary by director Shola Lynch (Chisholm ’72), conveys most strongly about the professor, activist, icon and force of nature at its center. The subject of songs by musicians including The Rolling Stones and John Lennon and Yoko Ono, at the age of 68 Davis still glows with the charisma, warmth and fierce intellect that brings the film’s extensive archival material—from personal letters to lectures to her extensive FBI files—to life. Lynch’s film, whose producers include Jay-Z, Will Smith and Jada Pinkett Smith, is a valuable complement to studies of Davis’s books and speeches, which remain all too resonant and relevant today. When Free Angela and All Political Prisoners premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival, Angela Davis was once again thronged by reporters and photographers, flashbulbs and staccato questions. Once again, she lifted her head, straightened her back, and stood tall.

In this conversation, Davis discusses the filmmaking process, explains what it means to be a “political prisoner,” and contextualizes her work for a new generation.

Filmmaker: How did you become involved in the documentary Free Angela and All Political Prisoners?

Angela Davis: The director, Shola Lynch, is a friend of my niece [performer Eisa Davis, who portrays Angela Davis in the film’s re-enacted scenes]. Shola approached me with the idea and I thought about it… It took a while before she persuaded me. [laughs] We had a number of conversations and finally I decided it might be a good thing. Sometimes it is important for a younger person to have a fresh new perspective on historical events. But from the beginning, I said to Shola, “This is your film; this is your perspective on that era.” I did lots of interviews and had lots of discussions with her but in the end, it’s her work.

I am not interested in people learning more about my life. However, I am interested in people recognizing the power of the campaign that developed around my case. Large numbers became involved and many of them came to feel as if it was their story as well. It’s important to convey to new generations that it is possible to join together and feel solidarity and togetherness across racial, ethnic, economic, gender and national borders. We could use some of that today.

Filmmaker: What do you think of our current political moment?

Davis: It’s a difficult moment given the economic crises all over the world, but at the same time there have been sparks of hope. The revolutions in the Middle East gave some hope to people around the world; so did the Occupy movement. We need some staying power. We need to feel that it is possible to pursue things in the U.S. such as free health care, which we still don’t have… even though Barack Obama is quite right when he boasts that he was responsible for the first major legislation on health care in the history of the country since the New Deal.

We still have a long way to go. We may be powerless as individuals—and even someone like Obama may be relatively powerless as an individual—to do things that will be bring us a better world. But if we come together, we can build movements and put pressure on the major political figures. This is what we need to be doing in the coming months before the election. The first time around, we elected Obama for what that election meant: the historical election of an African-American to the presidency. We were doing it for him. This time, we need to think about ourselves. We need to do it for us. Then, we need to continue that movement after the election.

Filmmaker: The title of the film is Free Angela & All Political Prisoners; what does the phrase “political prisoner” mean to you?

Davis: A political prisoner is someone who is imprisoned for his or her political beliefs or affiliations. Mumia Abu-Jamal, for example, is still in prison. But at the same time, we can argue that there is a broader definition of “political prisoner”: those imprisoned because of the overall political situation. In the United States, of course, there are more people incarcerated than anywhere else in the world. Prison has become the default solution for problems that should really be solved by educational institutions, health care, housing, etc. The concept of a political prisoner cannot remain static.

I’m glad that Shola used the title Free Angela & All Political Prisoners because that was an issue around which we had major arguments as the case was unfolding. There were many people who were willing to support me, but they didn’t necessarily want to get involved in the bigger issues. When the campaign around my case began to develop, I and other comrades argued that it had to be a campaign not only focused on me as an individual but on the larger question of political repression. At first, the organization was called “National United Committee to Free Angela Davis,” but it came to be called “National United Committee to Free Angela Davis & All Political Prisoners.” As soon as I was freed, we began to work on other cases. We created another organization called the “National Alliance Against Racism and Political Repression,” and I guess you might say that since then, I’ve been working consistently on prisoners’ rights, political incarceration and the racist implications of the prison system.

Filmmaker: In what way were you a “political” prisoner?

Davis: I was involved in a number of political organizations: I had been active in the Black Panther Party, I had been active in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and I joined the Communist Party. When I was first singled out and I lost my job teaching at UCLA, it was for my membership in the Communist Party.

When I was charged with murder, kidnapping and conspiracy, my Communist affiliation and my background in the Black Panther Party made me an easy target. And as a matter of fact, the Attorney General asked potential jurors whether they thought I was a “political prisoner” as part of his jury selection. He did not want to take those who thought I was a political prisoner; instead, he argued, I was in jail only on criminal charges. Of course, the U.S. doesn’t have a category for “political prisoners,” so people who are incarcerated for their political beliefs are always charged with criminal charges.

To this day, in the U.S. it is still said there are no political prisoners. Unlike South Africa, for example, which acknowledged Nelson Mandela as a political prisoner, here we have the guise of democracy. We’re supposed to be inhabiting a country in which people have the right to free speech and political affiliation. When I was fired simply for being a member of the Communist Party, I discovered that was not the case.

Filmmaker: In retrospect, your firing is seems much clearer than the court case, which has many shades of gray.

Davis: Well, the second time I was fired from UCLA it was because of my activity in support of the Soledad Brothers [George Jackson, Fleeta Drumgo and John Clutchette, who had been incarcerated in Soledad Prison]. So that was, again, a question of political activities and political issues.

Filmmaker: Was the administration upfront about your political activity as the reason for your second firing, too?

Davis: Oh yeah. “Activity unbecoming of a professor”: I wasn’t supposed to be speaking at rallies or involved politically off the campus. Which is, of course, ridiculous.

Filmmaker: Today, with everyone’s public persona so easy to access, it can be very hard to know where your professional responsibilities end and your private beliefs and rights as a civilian and a citizen begin.

Davis: Yes, that’s true. When I was teaching at UCLA, there were those who argued that because I was a Communist, I would be indoctrinating my students rather than teaching them. But I’ve always made a practice of telling my students what my political affiliations and principles are and then asking them to choose their own. Rather than assume that I could be objective and my political ideas would not insinuate themselves into what I was teaching, I would say to my students, “This is what I believe. I am not asking you to join me, but you need to know what I believe in order to judge for yourselves my remarks on any particular subject.”

Filmmaker: I can’t think of a single one of my history teachers making clear their political opinions.

Davis: Well, I was teaching Marxism so…[laughs] I was hired to teach a subject that I had been involved with on a practical level for a very long time.

Filmmaker: Today, Marxism remains relevant; in fact, it seems to be referenced more frequently than ever.

Davis: Capitalism is still with us, and Marx developed the most compelling analysis of capitalism. I never saw Marx as a philosopher who informed us about what the revolution was going to be like or what would come after capitalism. He provided a way to understand the world we inhabit and the extent to which political economies insinuate themselves into all aspects of our lives. That was true 50 years ago when I first encountered Marx but today, with the impact of global capitalism, it’s even more true. I could never have imagined the degree to which capitalism would develop.

To use an academic term, capitalism has overdetermined everything. You might say that even people’s dreams are capitalist dreams. As a professor, I see students who are professionalizing themselves even before they even learn what they need to know in order to go on the market; the assumption is that the market is everything.

This is capitalism. We used to be able to distinguish more clearly between capitalism and democracy. But now, people all over the world assume that democracy is just a synonym for capitalism. In the counties of the southern region, like in Africa, economies have been completely transformed into capitalist economies–even though the majority of people live in abject poverty and it doesn’t make sense to have an economy that is rooted in profit when you are trying to satisfy the needs of such vast numbers of people.

We have to work through this issue. This is why the Occupy movement erupted as it did: it was an indication that we need to find a new vocabulary to talk about capitalism publicly. It is now possible to talk about, to criticize capitalism in a way that may not have been possible even five years ago.

Filmmaker: Where does feminism fit into this?

Davis: I see feminism, not so much as emphasizing the rights of women—although it does—but as a way of understanding the interconnectedness of gender, race, class, sexuality, the economy and trans-nationalism. Feminism is one of the most important strategies for helping us to understand these issues and the ways they are tied together. More than ever, what we need is a Marxist-inflected feminism—that’s the best strategy at this particular moment in history.

Livia Bloom is a film curator and the Director of Exhibition and Broadcast at Icarus Films.

Special thanks to Brian Geldin, GAT.