Back to selection

Back to selection

Five Questions with Radio Unnameable Directors Paul Lovelace and Jessica Wolfson

Today Kino Lorber releases Paul Lovelace and Jessica Wolfson’s documentary Radio Unnameable, starting with an exclusive run at Film Forum in New York City. The following interview was originally published on the eve of the film’s screening at BAMcinemaFest.

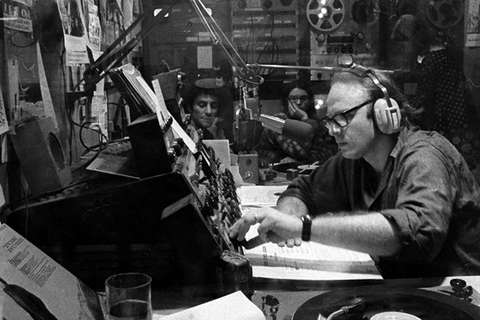

For decades, Bob Fass has been a unique voice on the airwaves of New York City’s freeform radio station WBAI with his show “Radio Unnameable.” From hosting a young Bob Dylan to organizing spontaneous youth gatherings with the Yippies, Fass has come to define an era of radio that had a profound influence on our culture. In their new documentary film Radio Unnameable, Paul Lovelace and Jessica Wolfson tell Fass’ story by utilizing a treasure trove of archival material, interviews and audio (which is constantly updated and can be sampled here). After premiering at the Full Frame Documentary Film Festival, Radio Unnameable screens at the BAMcinemaFest today.

Filmmaker: Radio is such a personal experience; for many people, the magic of Bob Fass lies in the power and focus of his voice on the radio and the way in which that voice acts within their own day to day lives. I am wondering if you can talk about the push and pull of creating a visual landscape for Fass’ audio universe and how your own experience of Fass’ late night New York City shaped the visual strategy of the film.

Lovelace and Wolfson: The biggest challenge at the onset was how do we make a film about radio visual. For the most part, listening to the radio is an extremely personal activity. So we wanted emulate that and to treat the visual elements in a visceral fashion, rather than being literal in depicting on the screen what we are hearing on the air. We utilized a wide variety of source material, trying to stay true to the formats used in each time period – film for the 1960s and 70s, Hi-8 and VHS for the 80s and 90s and HD for the present day. Rather than relying on stock houses, we searched out individual filmmakers and photographers, both working professionals and average listeners, who shot their own material over the years. For the present day, we spent many nights driving around the city with our cinematographer John Pirozzi, exploring neighborhoods and capturing our own perspective. New York City after midnight was our canvas and “Radio Unnameable” was our guide.

Filmmaker: There are literally thousands of hours of archival audio from Fass’ career. How did you get a handle on that material and can you discuss how you whittled it down to the incredible moments that made it into the film? Can you give an example of a great moment that did not make it into the film and explain the choice to exclude it?

Lovelace and Wolfson: When we started the project, Bob and his wife Lynnie held in their possession 5,000 or so open reel audio tapes, thousands of slides, photographs, film, video, cassettes, ephemera and so on. None of this was organized in any coherent fashion. One of our archival mentors, Mitch Blank, suggested that an army be assembled to take the material and make it accessible. So over the course of a weekend in 2008, 40 or so volunteers organized the open reel audio tapes. We created a searchable database with information written on the tape boxes. That gave us somewhere to start, but there was still an unbelievable amount of material to transfer and listen to. We had to be somewhat judicious because it was impossible to listen to everything. For example, for an event like the 1967 Fly-In, there would be a week or so of planning on the air beforehand and discussions about the event afterward that would total about 60 hours of audio recordings. We would have to listen to and whittle that to just a few minutes for the film. It was a lot of work, but massively rewarding. We were able to hear this captivating radio that hadn’t been heard in close to 50 years.

We always knew there was going to be a lot of amazing moments that we couldn’t fit into a 90-minute movie. One example was in 1974, when Yippie and Realist founder Paul Krassner and Bob Fass did this wild program the night Nixon gave his resignation, with audio collages, phone calls, pranks, among other lunacy. Another show we loved but couldn’t fit in the film was when a teenage girl called Bob to lecture him on the evils of recreational drug use. Fortunately there is a serious effort under way to restore these reels and make them accessible. We are also previewing select audio from “Radio Unnameable” on our website.

Filmmaker: Your film showcases the heyday of freeform radio as a community platform where individuals who shared all sorts of social concerns, from politics to public health to sexual liberation to personal depression, really gathered together to act. As such, the movie really feels alive to today, to burgeoning social movements and the migration to the internet and social media as the platform for these activities. Do you feel the vitality and urgency of radio has suffered because of this shift? How do you feel Bob Fass and his story fits into this new world?

Lovelace and Wolfson: Like all technological innovations, radio has to adapt. And in many cases it has. When Bob started, there wasn’t a lot of competition on the airwaves, certainly nothing as free and creative as “Radio Unnameable.” The internet has democratized media and allowed anyone and everyone to have their own show or station. This is both beneficial but also problematic as it can be argued that there is too much choice and sometime the quality of programming suffers. We always asked when shooting our interviews, “Could a person like Bob Fass, just starting out, thrive in today’s media culture? Would he be able to have the same freedoms that he was allowed on WBAI, a station with a huge listenership, right in the middle of the FM dial in the nation’s largest media market?” We think the answer is yes, but it would be operating on a far different terrain. That being said, it is pretty remarkable that 50 years later, Bob Fass is still on WBAI doing the same show, with the same spontaneity, taking free speech as far as it can go.

Filmmaker: From a non-fiction filmmaking perspective, I imagine the issue of rights and clearances for a film about a DJ who had a profound influence on the music scene of the 1960’s was very important to shaping the film. Can you talk about picking and choosing the film’s musical elements? How much did Bob help or influence in gaining access to material?

Lovelace and Wolfson: “Radio Unnameable” has been the after party to the downtown scene for some time now. The list of musical guests who have appeared on his program over the years is mind-boggling. This was certainly a mixed blessing when choosing what to showcase in the film. Someday we hope there will be some sort of compilation that highlights music that we couldn’t include. But any film soundtrack that features Buffy Sainte-Marie, Karen Dalton, Garland Jeffreys, David Bromberg and Hamza El Din isn’t a bad place to start.

We are also very proud of the original music in the film. This was composed by one of our favorite musicians, Jeffrey Lewis. He has been a regular presence on Bob’s show for some time now and was able to bring his own magic to the project.

Filmmaker: I am wondering if you can talk about your subject, Bob Fass, the process of securing his participation in the film and working with him. Obviously, non-fiction films live and die by their access to their subjects; what drew you to Bob Fass to begin with and how was your initial relationship to and with him transformed by the experience of making the film?

Lovelace and Wolfson: We heard about Bob through Peter Stampfel, a musician friend of ours (and the subject of Paul’s previous film he co-directed called The Holy Modal Rounders… Bound To Lose). Peter has been a regular guest on “Radio Unnameable” since the mid 1960s and he would talk about this crazy radio program that was unlike anything on the air, then or now. Then we heard about Bob Fass’s immense archive and all the incredible events that he had been a part of and saw the backbones of a story we wanted to tell. We called him up and pitched the idea of making a film. Immediately we were drawn in by Bob and his wife Lynnie’s warmth and generosity. They gave us full access to all of their materials, which we spent many years digging through. Over the course of making the film we have continued to maintain a close relationship with them, which has made this lengthy process immensely enjoyable.