Back to selection

Back to selection

Nara Garber & Betsy Nagler’s Flat Daddy

Nara Garber & Betsy Nagler’s Flat Daddy is released on VOD on November 6. The following was originally published on the eve of its Doc NYC premiere in 2011.

In the corpus of documentaries that have come out of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, we’ve seen a gradual progression from the outward to the inward — immersive forays into the battlefield giving way to subtler studies of the wartime psyche. Yet the majority of them have focused on the soldier’s experience of war. Flat Daddy sets itself apart by focusing on the people who feel war perhaps the deepest: military families put on hold or torn apart by the absence of their loved ones serving abroad.

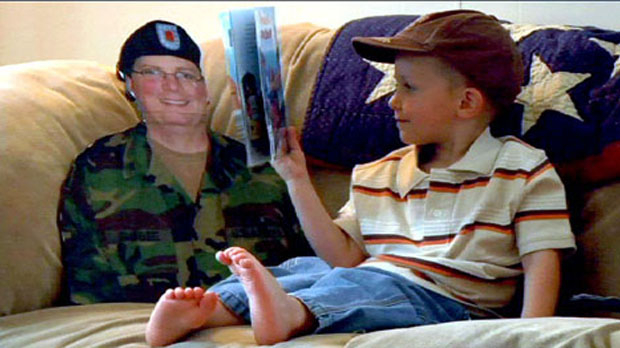

Directed by Nara Garber and Betsy Nagler, the film takes its name from the life-sized cardboard cutouts of servicemen and women (interchangeably called “Flat Daddies,” “Flat Mommies” or “Flat Soldiers”) designed to help families connect with their relatives during their deployments. Originating from the Iraq War, these waist-up portraits have increased production as the effort in Afghanistan has pushed on year after year.

Flat Daddy follows four military families throughout the U.S. as they incorporate war into their daily lives. For the Stephens family in New York, the Winter family in Minnesota and the Bugbee family in Maine, Flat Daddies serve as transitional tools to help children remember their parents once they return from their deployments. For the Ramirez-Vance family in Nevada, they unfortunately serve a more lasting purpose: to memorialize a son killed in combat.

Garber and Nagler drift in and out of the families’ lives with compassion, accompanying them throughout periods of separation and reunion. Using Flat Daddies as a poignant metaphor for absence, they tell the lesser-told stories of everyday Americans fighting the war within.

Filmmaker sat down with the directors to discuss their process of making the film, the disconnect between military families and the civilian population, and the realities of living in a post-draft society.

Filmmaker: How did you two come to work together on this project?

Betsy Nagler: I had read a really interesting article in the New York Times about how Flat Daddies started and progressed. And what was really powerful about it was a picture of a little boy sitting next to his Flat Daddy on a swing. It was just a very striking image and it had an immediate visual hook: “What is this?” And it turned out that Nara had actually read the same article.

Filmmaker: Did you know each other up until that point?

Nara Garber: Not at the time that article ran. This was September of 2006, and we met at a birthday party of a mutual friend in the summer of 2007.

Filmmaker: And how did the article come in the conversation?

Nagler: We took the train home together from this party and talked about filmmaking. At this point I was in touch with a contact in Maine, the woman who runs the Family Program there and who started the Flat Daddy program. She told me there was a homecoming coming up in a week or two and I thought that would be a really good place to start. So I was looking for someone to work with.

Garber: One of my big concerns was that this had been a front page article in the New York Times. You figure that there are so many people out there just waiting for inspiration to begin work on a documentary. And this was so visually compelling and arresting you’re thinking, “Somebody’s gotta be making this film.” I remember that that was one of my first questions for Betsy. And she said, “No, I’ve got Google Alerts going and to my knowledge there’s nothing going on right now.” That was about ten days before we had to go up to Maine.

Filmmaker: Aside from the immediacy of the situation, did you foresee any obstacles to the project?

Garber: Well, we’re both stereotypical left-leaning New Yorkers. So we were wondering if that was going to be a problem.

Filmmaker: Was it?

Garber: Not at all.

Nagler: We were weary about that at that first, so we took precautions. I took a bumper sticker off my car that I thought might be offensive—”Republicans for Voldemort,” which a lot of people don’t get. [Laughs]

Garber: We were speaking to so many people. Our first interview on that trip was with a Master Sgt. 1st Class who directs the Maine National Guard Family Program. She had been through infinite interviews about Flat Daddies, because it was kind of a novelty at that time. But none of the families we met had been on camera before, so there was this kind of trust. If they agreed to speak to us, then they knew we were in it for a good reason.

Filmmaker: Many of the documentaries that have come out about the wars have taken an apolitical route — offering character studies or experiential storytelling instead of polemics. Flat Daddy falls neatly alongside these films in that sense. Did you consider making the film more political at any point?

Nagler: People in the army and the military are very much about doing their duty. They didn’t want to talk about why the war was happening or how they felt about it. They were like, “The President is the Commander-in-Chief. I do what he says. He’s my boss.” That’s kind of their attitude. We did often try to turn the conversations to politics. But it became apparent early on that a lot of the people’s politics weren’t relevant to what they were doing.

Filmmaker: Was it difficult to gain access to your subjects during such pivotal times of their lives? The soldiers are only home for so long, and you were present for a good amount of it, right?

Nagler: We spent time with two of the families when they had [relatives] who were deployed home on leave. But we spent most of the time with the families who were home all the time. That was just everyday life. But it’s everyday life with a certain person absent — a mother and father [in the case of the Winter family]. And by the time soldiers came home, I think the families were comfortable with us and they really wanted to tell their stories. They knew that this was an important part of their stories.

Garber: It was important to know that this was the only opportunity these families have to reconnect. They really needed that time, and [we] could have really disrupted the status quo and the equilibrium in the family if we had been present the entire time. So we were there when the soldiers came home and when they left. But they did have time as families to themselves, obviously.

Filmmaker: How did you go about narrowing your focus to your four families?

Nagler: At first it was many different people. We originally settled on five that we would follow throughout the course of that year. We had two families from Maine that were kind of in competition with each other. We would have liked to have kept them both, but it became apparent once we started screening the film for people that it was unwieldy with five families.

Garber: Losing that fifth family was tough, and it represented an aspect of that deployment story that our film doesn’t dwell on as much right now. It was a tough balance. The family that we filmed in Las Vegas (the Ramirez-Vance family) who lost a child is the only family that deals with death. And because there isn’t as much of a narrative progression with that family, some people were saying, “There isn’t the same urgency to that narrative driving it forward, maybe you should lose that family.” And it led to a really interesting discussion because we all came to the realization that mourning doesn’t progress; it always sticks with you. And that kind of underscores all the other stories. You have to know that death is a possible consequence of war, and it’s something that’s on the mind of these military families all the time.

Filmmaker: When did your focus shift from the Flat Daddies to a more in-depth portrait of what military families go through on a daily basis?

Garber: That happened on our first trip to Maine. We started to realize what these families are going through is much more complex than can be symbolized by the cardboard cutouts.

Nagler: Flat Daddies are a powerful visual metaphor and you can make a short film about them, while touching on other things in a more superficial way. But in each of the places that we were going, we found different stories: “It would be really great to stop and see this family here, or see this family here.” And the more we did that the more we started to see that these stories were super powerful and it was going to be hard to just leave them with a little piece.

Garber: Betsy and I would send each other pieces on Flat Daddies that we found online. We would see these little news programs. There would be a homecoming, and some kid would be at the airport with a Flat Daddy, and they would do a little 3-minute news piece. And if you focus on the Flat Daddy, that’s pretty much what you get. It’s going to be, “Oh, isn’t that cute,” or “Oh, isn’t that sad.” Sad, weird, ironic…

Nagler: There was a lot of, “Oh, isn’t that weird.” And I think it’s easy for it to come across that way, but the more you come to understand how it works for the families the more you understand what it means. And that’s when you really want to go deeper.

Filmmaker: What do you think about the actual utility of Flat Daddies?

Nagler: They actually work!

Garber: We said to people recently that we are both good proxies for audience members because we started out a little skeptically. We thought, “What an interesting metaphor.” “What a peculiar metaphor.” That weirdness was bundled into our initial response. And then we filmed the Bugbee family in northern Maine, the mother with two young kids who were two and three when her husband deployed. They had two Flat Daddies. And the kids really were hands-on with the Flat Daddies. The neck has to be supported by popsicle sticks because they got so much use!

Filmmaker: Do they serve a different function for military families whose relatives died in combat, as in the case of the Ramirez-Vance family?

Garber: [Marina Vance] also had a cutout of her son to march with in a public parade. So it was not just having it in her home, it was making the decision to step outside and actually show that. And one thing we heard from families again and again was, “It’s a hard thing to lose your child, and everyone assumes you don’t want to talk about the loss. But there’s nothing you really want to do more than keep that memory alive and talk about it.” So this visual manifestation of your fallen child is a wonderful thing in that regard.

Nagler: It was very helpful for the Ramirez-Vance family. Because that story is about the process of grief, you see [Marina Vance, the mother] develop a new relationship with her son. I read recently that the process of grief is not forgetting the person, but developing a new relationship with them now that they’re not here. How do you not let a person go and put them into a new part of your life where they can still continue to exist? I think that the Flat Daddy helped her continue to talk about him and be close to him. I think it was more of a beginning for her to get to a place where she had a better relationship with him than constantly mourning him.

Filmmaker: The film comes out ten years after we first entered Afghanistan. Did the issue of war fatigue effect your process of structuring the film?

Garber: I don’t think that affected the structure. And without being defensive, I think it’s so important to keep this dialogue alive. One thing that we want to continue to emphasize is that families deal with trials and tribulations not only during the deployment but after the deployment. For a family to be torn apart like that, even for a soldier to come home with no dismemberment or physical injuries… imagine if your spouse went on a 12-month long business trip. That’s not so easy. Now have that business trip be in a war zone where there’s so much anxiety on one side. There are resentments that build up and dialogues that need to continue.

We were invited to participate in Military Appreciation Day at the Stewart Air National Guard Base up in Newburgh, New York. And they had something like 200 members of their national guard unit deployed very recently to Afghanistan. And that was a shock to find out that National Guard men and women are still deploying in those numbers. I knew active duty military are still cycling through Afghanistan, but here was a community of citizen soldiers who were still going and going and going. These are people who are in the community until they get deployed. So that does actually impact the community when their family structures fall apart, if they have difficulties when they come back, if homes are foreclosed because payments aren’t paid. All of that really impacts the community on a very direct level. And so just to be aware that there are military families in your community is something that we hope the film will wake people up to.

Filmmaker: What is your sense of the perception of civilians toward military families and returning soldiers?

Nagler: The families are more invisible obviously because they don’t wear the uniforms. Also, the stoic nature of the soldiers rubs off on them. They don’t like to talk about what’s difficult and what they need help with — if nobody’s there to mow their lawn when they’re picking their kids up from school — nobody likes to talk about that. And in terms of how civilians are relating to people who are in the military, I think there is a divide, a lack of awareness, and also a certain amount of fear actually.

Garber: And I think it’s the reality of being in a post-draft society. I mean, when there was a draft there was the possibility of somebody in your immediate family serving. Now it’s such a matter of choice. There are some economic disparities that come into play, some geographical disparities that come into play, there are different commitments to service in parts of the country that we observed. But here in New York City, it’s just not an expectation that many people grow up with. So it’s very easy to keep that entirely at arm’s length because you can know that you will not have to have that experience.

Filmmaker: Did you find that soldiers enlisted in the military for different reasons?

Nagler: Very much. I can only speak of the people that we know, but there are economic reasons for a lot of people, especially in places like Maine, which are economically depressed. One of the families that didn’t make the final cut went through bankruptcy unfortunately. [The husband] had gotten an Associates degree and realized he was never going to be able to pay it off without joining the National Guard.

Garber: In the Midwest, there seemed to be an old fashioned commitment to service and a real sense of duty. It’s not a language that I grew up hearing in my own childhood. There was one woman who had been a State Senator for twenty years, and her son was actually killed in Iraq. He was 43 when he was killed in action, and his mother was so vocally opposed to the war. And her son said to her when he re-deployed: “Mom, I have to go over to protect the other kids.” There is no way he could have been the son of that mother without having a very active thought process about the politics of the war. But it was about the service, it was about taking care of the younger kids.

Filmmaker: How did you react to some of the marital problems that the Bugbee family was dealing with?

Nagler: Well, we actually discovered a lot of those situations later when we were looking at the footage. And we thought [the Bugbee’s] marriage was okay at that point. Going back and interviewing them after they were separated was really something we had to be sensitive about. We were very careful to say, “We don’t want to make this uncomfortable for you, but this is part of the story,” and they were on board with that. And because divorce has become so common in these situations they really felt it was a story that needed to be told, and they were helpful in letting us tell it.

Filmmaker: What is your outreach strategy for the film?

Garber: Every time we’ve had to set up something — whether it’s the Kickstarter campaign, or DOC NYC, or the production itself — these have been great opportunities for us to meet organizations that tap into the very community that we’re trying to reach out to. Recently we announced the premiere on Facebook and we’ve been getting feedback from people who have said, “It would be great if we could have a screening in this area. Can I help host one?” So we’ve basically been building on all of these connections. We’re hoping we can find facilitators in communities working with organizations we already know to create an environment that feels safe for both civilian families and military families to screen the film, talk about it, and have an opportunity to open up about personal experiences, shared experiences, and really come together as a community.

Filmmaker: Where do you see Flat Daddy fitting alongside the other documentaries that have come out about the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq?

Nagler: I think that our film is much more subtle because we don’t go over there, because we don’t see the fighting, because it really is about the everyday lives of these families and how those everyday lives are different. You know, there’s a huge piece missing from those everyday lives.

Garber: I actually love the fact that our families lead subtler lives. People would say, “Is there a family whose home was foreclosed on?” “Did one of the soldiers come back physically injured?” It’s so quiet that it applies to everybody. These are real life situations that are completely relatable. As a civilian, you can completely understand how things would play out that way. And as someone in the military, you realize that, “Yes, it’s a struggle for everybody. It’s a struggle for the whole family. Everybody has to play a support role.”

Nagler: And I think it reflects the rhythm of everyday life. You know, the rhythm of everyday life is that everything is fine until something comes and upsets it. We talked about the shadow of death hanging over everything, and that is one of the things that can happen when you have someone deployed. We tried to show that life is as normal as it can be, until it’s not.