Back to selection

Back to selection

Rick Linklater Talks the Gotham-nominated Bernie

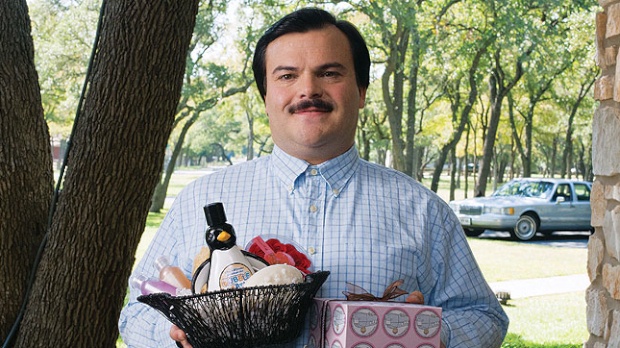

Bernie Tiede was the popular person in Carthage. We know this because the small East Texas town residents tell us themselves. They sit on lawns and in office chairs and talk to the camera in Richard Linklater’s new film Bernie, nominated for Gotham Awards for Best Feature and Best Ensemble Performance. This ensemble collectively tells of how Bernie (played in flashback by Jack Black) first came to town in 1985 as an assistant funeral director. Soon, they say, he led Carthaginians through the local church choir, town theater productions, and Little League, even helping people with their tax returns. He loved everyone and tried to do right by everyone, including the nasty banker’s widow, Marjorie Nugent (Shirley MacLaine). For a time Bernie and Ms. Nugent were happy companions, traveling the world together. But he failed, ultimately, to defeat the controlling and possessive parts of her. When it got to be too much, he lost control, shot her four times, and hid her body in a freezer.

To the town prosecutor, Danny Buck Davidson (Matthew McConaughey), the murder was an act of cold-blooded calculation; to everyone else in Carthage, Bernie had tried and failed to do the right thing. Their sympathy for him was so great that Davidson had to take him out of Carthage and to a neighboring town to be tried. By the time that the film’s trial scenes arrive, though, we’re already well on the townspeople’s side. They and the movie together suggest that you could only condemn Bernie if you didn’t know him.

Linklater’s always been a greatly sympathetic director, encouraging you to feel for a wide variety of people, whether high-school bullies (Dazed and Confused [1993]), Depression-era outlaws (The Newton Boys [1998]), or intellectuals doing their desperate best to avoid adulterously, inevitably falling in love (Before Sunset [2004]). He had been interested in making a film about Bernie ever since reading about the man shortly before the murder trial. On the eve of the Gotham Awards, Linklater defends Bernie.

Why mix professional actors with real Carthage residents?

Hopefully you can’t tell the difference too much, but obviously it had something to do with the quest for the authenticity of the region. In the script they are all referred to as town Gossips and they were the key narrative device. Various movies have incorporated brief interviews with characters in and around the story – think Reds (1981) – but I hadn’t really seen a story told specifically through a small-town gossip circle. Besides being funny, it perfectly fits in here because that’s how this story was originally received. Ms. Nugent was gone and Bernie was in jail and not giving interviews, so it became this avalanche of peoples’ perspectives on them and on the murder. At the end of the day, both Bernie and Mrs. Nugent are enigmatic. We have our hunches, people tell stories, but there’s a certain unknowability at the heart of it. But if you’ve lived in a small town, like I did growing up, you know the social power of gossip. Everyone’s got their own point of view on themselves, but in a small town, you’re what everybody says you kind of are. If everyone says you’re a bitch, you’re a bitch. If everyone says you’re a nice guy, you’re a nice guy. Gossip’s a real, controlling force, for better and for worse. The trick was to incorporate the gossips into the story—at the trial, their restaurants, and so on.

When you auditioned the townspeople, what were you looking for?

What you’d look for in any actor, really. All of the Gossips’ dialogue was scripted, so it was finding people who could take a written text and perform it while still being their own unique selves. Not everyone can do that, no matter how funny and extroverted they might be. They were encouraged to throw in their own thoughts and ideas, and that often worked wonderfully. Some of them knew Ms. Nugent and Bernie and were able to add a line here and there.

At the beginning of the film, before we meet Bernie and Ms. Nugent, the actor Sonny Davis (playing a Carthage resident) outlines the map of Texas, including how Carthage fits into it. Why open this way?

Because I wanted to very precisely locate the film geographically. When most people outside of Texas think of what it looks like, they usually think of John Wayne movies or of Giant—huge, sprawling desert ranches. West Texas is a common reference point, as are the urban centers of Dallas or Houston. East Texas is hardly represented. There are no real large cities in East Texas. None. It’s a bunch of small towns ranging from 60 people to nearly 100,000. The plantation South pretty much ended there. If you go back to pre-Civil War, that part of the state had slaves, and Central and West Texas, founded primarily by European immigrants, really didn’t. The state was very divided on the vote to secede before the war. When I say I grew up in the woods—the thicket of pine trees, oak trees, cedar trees—people don’t really associate that with Texas, but it’s a big state. There are all these complexities, and the accents are very different from region to region. So I was trying to make a distinction—East Texas is much more Southern, and Central and West Texas are much more Southwest. When people ask me anything about Texas or about where I’m from, I do some much briefer version of that map.

What did you recognize in Carthage?

It was like Huntsville, the town I grew up in, which is a few hours South but still very much East Texas. How friendly and open and inclusive everyone is. In a place like that, you’re a good ‘ole boy or a good ‘ole gal until you prove differently. In other places you have to earn your way in, but there you’re accepted immediately until you prove you don’t belong. Ms. Nugent isolated herself by not being friendly, not caring what anyone thought, not doing all the little things that are expected. When I go back to visit my mom and go to the grocery store, I know I’m going to spend an extra 15-30 minutes there by running into people I went to high school with and catching up. It’s just what you do in a town like that. If you don’t like it, move to a bigger city where you can be anonymous. Bernie and Ms. Nugent, for different reasons, would have probably done better ultimately in much larger cities.

But the way that you tell the story, Bernie becomes so important to Carthage that whatever doubts or suspicions people have about him—his possibly being gay, whatever he was or did before arriving in town—don’t matter.

He was one of those positive forces that make it a good town to live in – a friendly, supportive person who actually cares about everybody. Big in the church, very social, and just trying to make Carthage as good as it can be. And trying to accept people the way that they are is a tradition in these places. That’s why you see all this selective forgiveness—some politician who’s on his fourth wife and ranting about family values, and people accept it. The dial can easily go more toward human frailty and away from hypocrisy. It’s hard to describe how Bernie could feel comfortable in such a conservative town, but there’s a lot of comfort to be had there.

How did you see music working in the movie?

It’s the atmosphere of Bernie’s life. Show tunes and hymns, all the church music. He’s someone who traveled the world with religious choirs. Music’s a big element, and I wanted the music of his life to fill the movie.

How did you pick your three lead actors—Jack Black, Shirley MacLaine, and Matthew McConaughey?

I had worked with Jack on School of Rock (2002), and I thought that he not only had a physical resemblance to Bernie, but also a great singing voice and actually something a little Bernie-like in his nature. I couldn’t think of anybody else. Can you? What great film actor can also sing like Jack?

I thought Shirley would be wonderful because she can play both the bitch and the starry-eyed girl. She’s still that sensual, flirty being that we see briefly during Ms. Nugent and Bernie’s honeymoon period where they were getting along and she was a little happy.

And Matthew grew up in Longview, which is the town next to Carthage, so I played the East Texas card, begging. Matthew has been in court as an actor a few times, but always on the defense side. This was the first time that he had ever been a prosecutor, so it’s very different. He said when he’s defended guys in movies he has always felt they’re guilty and deserve some punishment. But the one time that he’s prosecuting someone, it’s for something he doesn’t think deserves as harsh a sentence as his character’s doling out.

How were the ways you directed the professional actors different from the ways you directed the nonprofessionals?

Not much different, actually. Just trying to have an atmosphere where everyone can do their best work.

At the end of the film, you show Jack Black and the real Bernie together. Why?

How often do you get to see the star of the movie with the real person they’re portraying? Jack wanted to visit Bernie in prison, who I had been writing to. We were able to talk with him for a long time. Because of Jack’s celebrity, we got incredible access to his life in prison. We saw the craft shop he works in and his cell, and we met a lot of his friends. I came away with a better feeling about his life on the inside in that he’s made a life for himself. But it was really important for Jack, who absorbed every little thing about him—his accent, hs walk and general demeanor. I had a flip camera with me, and while they were talking, I shot a little footage and ending up using it.

Was it important to you that the audience be able to sympathize with Ms. Nugent and with Danny Buck as well as with Bernie?

I hope so. No one’s a monster or even wrong – they’re just being themselves. Danny Buck is a guy doing his job. He’s a little bit of a showboat, but that’s the nature of it. I admire him.

Ms. Nugent is somebody who seems destined to be terminally unhappy, and I think that the wealth makes her even unhappier. These days the richest people seem like the most pissed-off. They feel like the world’s closing in on them, like people are trying to take things from them, and they have the most to lose. Mrs. Nugent is a study in impatience, possessiveness, and paranoia, but she doesn’t get up in the morning saying, “I’m a bitch.” Bernie sees a person there and feels sorry for her in her isolation. He has a love for her that I think he does for all humanity. So it becomes a showdown between a woman who doesn’t care if she’s liked and a guy who wants to be liked so much. And Ms. Nugent wins. She proves to Bernie that he’s not as nice as he thinks he is. How twisted is that?

I understand that you attended the actual murder trial.

My co-writer Skip Hollandsworth and I were able to attend some of it, and saw all of Bernie’s testimony. At that point I had only read Skip’s article [“Midnight in the Garden of East Texas,” Texas Monthly, January 1998], where in the end it looks like it’s going to be difficult to prosecute Bernie at all. It seemed like such an odd story, and from East Texas, my own neck of the woods. We couldn’t have made that trial up. It was somewhere between a small-town circus and a picnic, with people selling food on the courthouse lawn. So much of the movie is exactly what happened, including things that Danny Buck did, like making the jury feel Bernie was some kind of elitist because he knew how to pronounce Les Miserables.

Do you believe that justice was done?

The prisons are full of people who are innocent, or who are doing a lot more time than they deserve to. They also let out guys who should never be free in society to harm again. This is just one more example of how completely strange our criminal justice system is. Bernie himself, outside of putting Ms. Nugent’s body in a freezer and delaying its discovery, never really tried to escape getting caught and being punished. People would have understood, I think, if he had discarded the body, or cut it up and fed it to the fish. But what he did sounded so strange on the surface, even though he was actually respecting the protocols of his profession in a twisted way. Once the trial was moved, it was a lot easier to prosecute him for his perceived “otherness.”

So to answer your question: Was justice done? Yes, but way too much. He got tried as if it were a premeditated murder for money, which doesn’t hold up when you realize (a) that he was the sole beneficiary of the estate, and (b) that the one thing that all premeditated murderers usually have in common is that they try to get away with it. He made no serious attempt. It was clearly a “murder with circumstances,” or temporary insanity. Some people don’t believe in that, but I think if there is such a thing, this was a case of it. He was really driven crazy by her, like a battered spouse might be, yet he’s ultimately doing the same amount of prison time as serial killers and raging psychopaths do.

To me, that’s the intriguing core of the story. Are we all Bernie? Do we know the ranges of our own capabilities? Do we know how we really are? People do end up killing people that they fundamentally loved. It happens all the time. I think Bernie is a reminder that even a nice guy could be capable of it. We all could be, given the right circumstances. And then it never makes sense on paper.