Back to selection

Back to selection

Family Matters

As a child growing up in Scituate, Mass., Nick Flynn was often left to explore on his own, and he got into varying degrees of trouble. Flynn’s parents were divorced and he had no contact with his father, living instead with his mother, who worked in a bakery. She remarried to a 21-year-old Vietnam vet, and, after their divorce, Flynn wound up living with her and a new boyfriend — a member of one of the largest drug smuggling rings in New England. Around the age of 18, Flynn started working for the smuggler — unloading fishing boats and as an electrician’s apprentice — and he’d get high every day to make the work bearable. Eventually the boyfriend got busted and Flynn had to show up in court to speak to his character.

Just a couple of years earlier, Flynn’s own estranged father wound up in prison. The elder Flynn began to write his son, sending him hundreds of letters. But it would be almost a decade before they’d unexpectedly meet face to face — at a homeless shelter, where Flynn was a social worker and his father, Jonathan, was seeking a room. This meeting and their subsequent relationship led Flynn to write his memoir, Another Bullshit Night In Suck City, which was how his father often described the experience of being homeless in Boston.

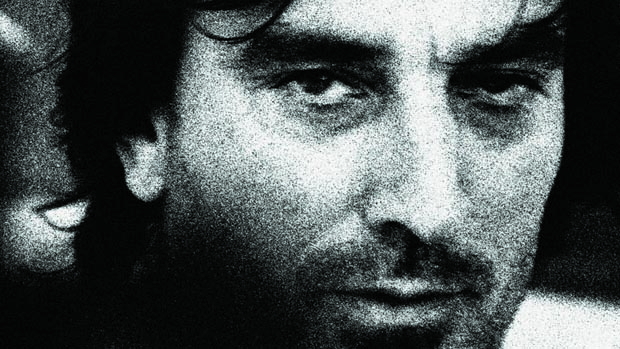

The book (published by Norton in 2004) won the PEN/Martha Albrand award, has been translated into more than 10 languages and is now a feature film, Being Flynn, written and directed by Paul Weitz (About A Boy). (“Bullshit” in the title apparently doesn’t fly with American moviegoers.) Robert De Niro plays Jonathan, Julianne Moore is Flynn’s mother and Paul Dano is the author as a young man. Flynn’s real-life wife, Lili Taylor, also appears in the film. Focus Features releases the film March 2.

“As soon as there was even a possibility of De Niro playing him, it just seemed perfect to me,” Flynn says. “He has that grandeur and menace at the same time.” And while many authors are excluded from a film’s production once the option agreement is signed, that wasn’t the case with Flynn, who regularly gave input on the film’s authenticity. “I got a lot of e-mail, photos and Dropbox things of De Niro in various costumes for me to comment on,” Flynn remembers of the preproduction. “De Niro looks nothing like my father, but once we settled on two or three costumes for him, and he let his hair grow long and combed it in a certain way, he eerily and suddenly started to become him in this really weird way.”

Before shooting, Flynn, Weitz and De Niro took a trip to Boston to visit Jonathan. When asked if his father got a kick out of meeting De Niro, Flynn replies, “No, he couldn’t care less. He was totally unimpressed, which De Niro seemed to love. My father just held forth for, like, two hours. He said some wonderful things. At one point I went to remind him again that this was Robert De Niro, and this was the director, and he called me a ‘wanton fucking goon-ball.’ We all wrote it down, like, ‘Oh that’s good, that’s good.’”

Being around the production, with his life coming full circle, inspired Flynn to write a new book about the experience, The Glass Flowers, which threads his current life through the movie production’s revisiting of his past. After all, you don’t stop living when you write a book or make a movie — a truism echoed by the tagline on the film’s poster: “We’re all works in progress.” Currently in draft form, The Glass Flowers goes from the film set back in time to an exhibition at the Harvard Museum of Natural History that his mother took him to when he was a boy. Both the flowers and the filmmaking process activate Flynn’s thoughts on representation. “They’re so unbelievably delicate, the glass — there’s something that happens to glass, even. Something happens to everything. Even the fiction that we create begins to break down.”

Since visiting his father with Weitz and De Niro, Flynn has been back to show his father the trailer for the film. “I showed him the trailer about 20 times. I explained to him, ‘Remember, you met Bob, and this is Paul Dano, and he’s me, and this is when we were at the shelter, and this is you driving a cab…’ The first time we went through it he really didn’t come alive. It didn’t quite sink in until I get punched in the eye, and then he really lit up. He was like, ‘Ah, that’s great!’ That was his favorite part through the whole thing, every time I showed it to him. He also liked the bit when De Niro says, ‘You are me. I made you.’ And then my father did the same voice. He was imitating De Niro, imitating him, and he did a good imitation. So, that was a nice moment.”