Back to selection

Back to selection

Tribeca 2013 Critic’s Notebook #2: Black (Out)Rage

So I’ll get right to it — the only truly great film I’ve seen at this year’s Tribeca Film Festival is Jason Osder’s searing Let the Fire Burn. A found-footage marvel with no narration and sparse title cards, it dives into the maelstrom that was the Philadelphia police’s tragic raid on the black separatist group MOVE’s West Philadelphia compound in 1985, during which the home, where 13 men, women and children lived, was fired upon 10,000 times, doused with unspeakable amounts of water and then finally firebombed, an event which led to nearly 70 other homes in the surrounding working class black community being destroyed. The subject of John Edgar Wideman’s PEN/Faulkner award-winning novel Philadelphia Fire, the story is brought to volcanic, penetrating life by Osder, a professor at George Washington University. He used all found materials, chiefly the video record of television newscasts from the day of the assault, a documentary from the mid ’70s about MOVE, footage of testimony from a bi-racial community panel put together in the wake of the destruction to make sense of the affair and most damningly, a deposition given by a 13-year-old child who lived in the home, and needs not to comment on them at all. They speak for themselves. It goes without saying that this masterpiece about an astounding and forgotten moment in recent American history should be seen far and wide; every American is an ambitious goal, so as many as possible will do. But let’s just start with you, anonymous reader, and we’ll go from there.

The feeling that Tribeca became the destination for films and filmmakers one may have expected to appear first elsewhere hovered over many festival titles this year, such as the pedigreed, high-profile Sundance lab project Bluebird, directed by Lance Edmands. Or the appearance of frequent SXSW darlings Josh and Benny Safdie with their latest, about ex-high school basketball standout Lenny Cooke. While both remain unseen by this critic, I did get a chance to encounter another film that would seem to fall into this category, Matt Creed’s Lily, a handsomely photographed story of one upper-class young woman’s struggle with breast cancer and the stifling boredom of having an older, pretentious, foreign boyfriend. Amy Grantham, donning a Jean Seberg/vintage Mia Farrow post-chemo haircut that she hides underneath a wig with over-accentuated bangs, is okay in the leading role, but the film never really takes off despite her efforts and ex-Safdie collaborator Brett Jutkiewicz’s impressive lensing and cutting. When she starts lashing out at her boyfriend or WASP-y mother, all you can help think is that the movie would probably work if Gena Rowlands was in it. But the character is drawn too thinly, and the entire arc of the narrative is too narrow, despite the high stakes of advanced illness, for even an above-average actress to breath life into it.

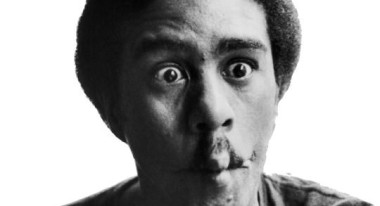

Richard Pryor is enjoying something of a renaissance, what with the magnificent retrospective BAMCinematek put together in February and now Roman Polanski: Wanted and Desired director Marina Zenovich’s new Showtime-financed documentary about the legendary comic, Richard Pryor: Omit the Logic. Authorized but probing, it details Pryor’s rise as a middlebrow Cosby-esque crossover act to his “Berkeley in the late 60’s”-bred transformations into a take-no-prisoners storyteller who brought the experiences and perspectives of working-class urban and ex-urban mid-to-late 20th century blacks to mainstream American audiences in a bold and entirely groundbreaking way. Pryor produced cathartic waves of laughter from the sex lives, addictions, familial relationships, and delicately concealed anger of the kind of people he almost never got to play on movie screens, even as he became the preeminent black movie star of the late ’70s and early ’80s.

His blow ups, both metaphorical and literal (he tried to kill himself using a bottle of rum, a freebase pipe and a butane lighter), are treated as painful of detail as his childhood living amongst pimps and prostitutes in his grandmother’s whorehouse. Yet the singular, unbridled brilliance of his comedy is never far from the picture’s heart, which indulges us with some of his finest acts in between commentary from those who knew him best and the scores who were unendingly influenced. The film manages not to be nearly as artful as one of Pryor’s own stand-up acts, but then, how could it? Generously burrowing into his filmography (although no The Mack!?) it manages to be better than most of the films he starred in in his megastar period.

The same can’t be said for Yves Montmayeur’s portrait of the filmmaker Michael Haneke, Michael H. Profession: Director. It’s not better than most (or any) of the Austrian sadomodernist’s movies, but it’s sure interesting to watch him work. Haneke sat down for interviews over a dozen years with Montmayeur, who goes behind the scenes of most of Haneke’s films, especially Amour, his most recent international provocation. Haneke is serious, but good humored. Clearly he fights for exactly what he wants on his set and doesn’t pull any punches when critiquing an actor. He’s much lighter hearted than his movies let on. All good to know. But Montmayeur doesn’t really get to the bottom of what Haneke thinks he’s trying to say. It was never going to be as simple as pointing a camera in his face or that of his collaborators and getting them to say Michael is describing the failure of modern European society to have coherent meanings other than pain, but it might have been worth a shot. Instead we get bemused platitudes. We’re happy to listen, but the film doesn’t live up to the promise of such a long-in-the-works expose.