Back to selection

Back to selection

Tribeca Film Festival

MSNBC’s nightly programs are manna, a much-needed counterbalance to the agitprop spewing from Fox News. Reading Stephen Holden’s preview of the Tribeca Film Festival in the April 16th edition of the Times, I wondered if we need more than ever an alternative print organ covering culture, in New York anyway, with the clout of the Times. Holden parrots Tribeca’s moldy marketing theme, then jumps to a questionable conclusion. “Because the festival…was born in the ashes of the World Trade Center as a community development project to revive the devastated economy of Lower Manhattan, you might say My Trip to Al-Qaeda is woven into Tribeca’s DNA.” My Trip to Al-Qaeda is Alex Gibney’s film of Lawrence Wright’s one-man play, which Wright adapted from his best-selling book The Looming Tower: Al-Qaeda and the Road to 9/11.

First of all, the idea for the festival began before 9/11. Few of the films at this point are even screened in Tribeca, as they used to be. I remember going down there every day, something I had only rarely done before; the strategy worked. It would be one thing for the festival itself to highlight Gibney, an Oscar winner who has three works screening at this year’s event. It’s another for a reputable newspaper to overlook a very decent and far more appropriate American indie film in the festival’s Encounters section—in fact, probably the Amerindie picture that could turn out to be this year’s Best in Show–that takes place in large part on 9/11, is sympathetic toward an olive-skinned, skull-capped, 10-year-old Muslim boy from New York who is harassed in Middle America because of the immediate backlash, and features one of the finest performances in recent memory.

The movie: The Space Between, directed without fuss by first-timer Travis Fine, an ex-regional pilot with lots of experience with the film’s backdrops but, alas, zero name recognition. The superb actor: Melissa Leo, she who stunned us in both Frozen River and 21 Grams, who here plays a burnt-out flight attendant–an alcoholic so high-strung that it takes little to trigger her fabulously quick gutter mouth—charged with accompanying the minor from New York to LA, where he has a scholarship to a prestigious Muslim school. Her path to redemption commences when all planes are grounded after the attacks on the WTC, where the kid’s immigrant father has been working in the top-floor restaurant. She takes the boy on an arduous overland journey to get him home. Leo, however, is 50, attractive but hardly an It girl or a household name. This is a fine example of the skewed collusion between media and spectacle.

Holden correctly notes that Sundance and Toronto “attract the best American independent films”—most critics know that the American narrative competition at Tribeca has never been its strong suit–so it’s no shock that the best fiction comes from outside the U.S., especially from Europe. (For reasons of space and the large number of films viewed, I’m going to focus on those I find worth much more than the price of admission.) The surprise this year is the dent made by films from Ireland. The two most impressive contain varying doses of that twinkly, uniquely Irish self-deprecating humor. They also feature performers who are terrific in their roles but hardly emanate star quality—and that is meant as a compliment.

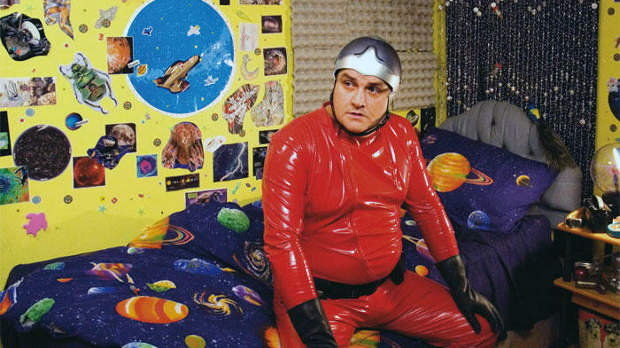

John Carney proves in Zonad, which he co-directed with brother Kieran Carney, that he can effectively tackle multiple genres, not merely the romantic quasi-musical of a chamber play that defined his brilliant Once. Zonad is a very well shot, edited, and directed spoof of cheesy B-movies of the ‘50s, from sci-fi to horror to teen romance to family comedy. (It may well be the most deftly directed movie in the festival.) The actors are excellent, especially Simon Delaney, who poses as the eponymous visitor from outer space after he escapes from a rehab center, in order to mooch off a gullible small-town family, seduce the local girls, and grab free pints in the pub. (Delaney was in the brothers’ short that was a precursor to this, shot in John Carney’s apartment in 2003, and, like the feature, produced by the ubiquitous Ed Guiney, who has been involved with such fine Irish productions as Omagh, The Magdalene Sisters, and the overlooked Guiltrip. I mention all this because part of the Irish film success story is explained by the collaborative nature of the community.)

Once Zonad has the village in the palm of his hand, his partner in escape, who has read about his buddy in the papers, appears in the town and announces himself as…Bonad (David Pearse)! He tells the locals that he will replace Zonad. The brothers Carney stay faithful to five-decade-old generic conventions but nevertheless succeed in appealing to a 2010 audience. It’s great fun; in fact, the Cinemania strand in which it appears, a mix of satirical, horror, and schlock films, may be Tribeca’s strongest.

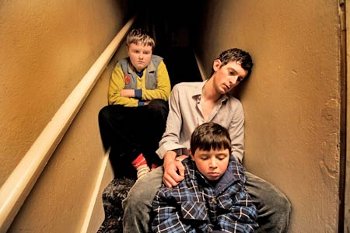

The other Irish movie about to create a buzz is the much more serious My Brothers, the directorial debut of Brit Paul Fraser, who wrote several screenplays for the British director Shane Meadows. In those he displayed a strong feel for provincial working-class environments; here he transposes it to a small Irish community over Halloween weekend, 1987. Three brothers, ages 17, 11, and 8, take off in a hijacked bakery van through the verdant Irish countryside for a beach resort to find a replacement for the inexpensive watch prized by their dying father; the eldest had caused it to crack. During the trip, the siblings fight, fart, and tease one another. The actors are so natural, their characters so realistically flawed, and their trip so well choreographed that it is unfortunate that Fraser and screenwriter Will Collins felt it necessary to toss in a nasty scene in which a pedophile pulls out his equipment as a come-on to the prepubescent middle brother.

Moving toward the continent…sort of. The discovery is a French/Canadian coproduction, Dog Pound, directed in English by Frenchman Kim Chapiron in Canada, which subs for Montana, with an all-Canadian cast playing American. Yet this is no euronorthameropudding: It is nicely integrated, reminiscent of the ‘70s films of the late British director Alan Clarke, set inside a juvenile detention facility in which gangs and guards compete for power. Chapiron knows how to handle crowds and kinesis in enclosed spaces, and his young actors are credible as bullies, victims, and upstarts. (Adam Butcher does a nice job as 17-year-old Butch, so full of rage that he explodes into ferocious displays of violence.) The atmosphere is Social Darwinist; corruption stains everyone, as it must if one is to survive.

I’m a big fan of Michael Winterbottom’s The Killer Inside Me, technically mostly a British production by a British director, but with an American cast bringing to life the troubling Jim Thompson novel. Since the film was in Sundance, and I wrote about it from Berlin for the upcoming print issue of Filmmaker, I’ll be brief. Winterbottom succeeds in translating a work of pulp literature, warts and all, to cinema. If you go to see a faithful adaptation of Thompson’s Texas, you should expect horrific violence. Some can not stomach it, but to call the film misogynistic, as many critics have, is to misinterpret the artistic translation from one medium to another. Casey Affleck’s psychopathic sheriff does beat and kill women, especially the prostitute portrayed by Jessica Alba, but it’s all there on the pages.

If only Turkish-German filmmaker Feo Aladag had excised a few ill-chosen scenes, her When We Leave would be a very good movie. A short synopsis sounds very been here/done that—a beautiful young Turkish-German woman leaves her husband in Turkey to return home with her young son to her émigré family in Berlin, but the kin she expected to take her in exact revenge for having tarnished their honor—yet Aladag gives the narrative a special spin. Umay (Sibel Kekilli) is gorgeous, but her marriage was a mistake from the get-go. Not only does her husband beat her, she would never be able to adjust to life in his orthodox village.

The men in her family are the most unforgiving, of course. Even her sweet younger brother eventually succumbs to the patriarchal pressure for expulsion and retaliation. The mother is conflicted, torn between love for her daughter and the need to save face in a tight-knit, conservative minority community. Umay is complex: She flirts with, then dates, a non-Turkish man she works with without a second thought to the consequences. The problem is that she, like Aladag, wants it both ways. Umay wants complete independence, yet she begs her relatives to accept her. Impossible. She is immature, and it costs her dearly. She lives in a hostel for women at an undisclosed location to protect herself and her child, yet shows up with him unannounced at her sister’s wedding. The character makes a misstep here, and so does Aladag.

The festival has a few gems from Asia. Filipino filmmaker Brillante Mendoza (Summer Heat, Slingshot) is back in form with the poignant Lola, which translates from Tagalog as Grandmother. Mendoza captures the poetry even in an urban slum, this one the perpetually flooded Malabon neighborhood of Manila. He interweaves the connected stories of two old grandmas: Lola Sepa’s grandson has been killed resisting a cell-phone thief; Lola Puring’s grandson is the robber. Without judgment, the director finds each woman sympathetic, caught in a quagmire of poverty, corruption, and sexism. The two eventually find common ground, even if one family buys the other off, but that’s a culturally-coded affair that is not for outsiders to judge. The lead actresses, one 84, the other 79, are perfectly understated.

Iranian director Mohammad Rasoulof is under arrest for opposing President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in his country’s recent elections. His achingly beautiful The White Meadows is a metaphor for the blind collective mentality dominant in a society like Iran’s and the price an individual thinker or doer must pay: An artist is blinded and becomes a prisoner on a remote island for daring to paint the sea red instead of blue; an attractive, flirtatious woman dies an untimely mysterious death. A middle-aged boatman navigates the waters between blindingly white salt marsh islands, collecting the tears of their ultra traditional inhabitants in small vials. Many of the residents are clad in black, setting them off strikingly against the harsh seascape. The film’s editor is acclaimed director Jafar Panahi (The Circle), who is also under arrest.

The quality of documentaries in Tribeca is more evenly matched between foreign and American than the fiction. The Israeli/German/Spanish coproduction Thieves by Law is directed by Alexander Gentelev, an Israeli who had emigrated from Russia. Formally the film is conventional, but the filmmaker’s access and subject matter are astounding. He interviewed three leaders of the Russian Mafia, eager for different reasons (mostly ego) to tell their stories, around which he constructs a history of the organization over the past few decades.

The set-up in Russia is unique: The gangsters become legitimate businessmen. And, for me anyway, there are a few revelations, like how so many married Jewish women so they could set up shop in Israel, which had more relaxed laws about their illicit commerce. One of them is in prison, but another lives a life of luxury in Cannes, from where his financial support of the Russian Orthodox Church reveals a theological complicity in underworld activities as strong as the Russian political establishment’s.

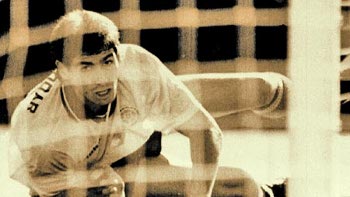

The American brothers Jeff Zimbalist and Michael Zimbalist successfully blend the related Colombian stories of drug lord Pablo Escobar and footballer Andres Escobar in The Two Escobars, which, with appealing visual panache and a rhythmic soundtrack, feels much more Latin American than North American. Once cocaine honchos began buying teams, football thrived, putting Colombia on the world sports map. This enabled the country’s team to go to the 1994 World Cup in the States, but veiled and unveiled threats of competing kingpins shadowed the players. Andres ended up inadvertently scoring a goal for the U.S. team, thereby causing his country to lose the key match against their hosts. Soon afterward he was killed in his hometown of Medellin in a revenge murder orchestrated by other narco biggies, who got off. The overused critics’ money-quote term riveting truly describes this film.

One of the most incredible movies at Tribeca is, at 49 minutes in length, probably the least commercial: Dustin Thompson’s avant-garde documentary Travelogues, one of curator Jon Gartenberg’s invaluable annual outside-the-bell-curve contributions to the festival’s slate. Thompson films a diary of sorts, with accompanying text, comprised of tableaux from his journeys, mainly in Germany, Italy, France, and California. He is a democratic tourist: a lover, an Italian cathedral, and surfers in a Munich river carry equal narrative weight. The mini-narratives, however, are distinguished by differing angles and speeds; form sets them apart. This is fantastic stuff, a festival film that makes you feel that life is worth living, and Tribeca worth attending.