Back to selection

Back to selection

Cannes 2013: Five Questions with The Congress Director Ari Folman

It’s been five years since Ari Folman came out with the Academy Award-nominated Waltz with Bashir, an animated personal combat story. He’s back with an incredibly ambitious project, The Congress, that blends real life with fantasy in an adaptation of Stanislaw Lem’s celebrated book. The movie opens with actress Robin Wright being scolded by her agent, played by Harvey Keitel, for all the poor choices she’s made throughout her career. Faced with a sick child and no job prospects, she meets with Jeff, the studio head of Miramount, a daunting figure played impeccably by Danny Huston.

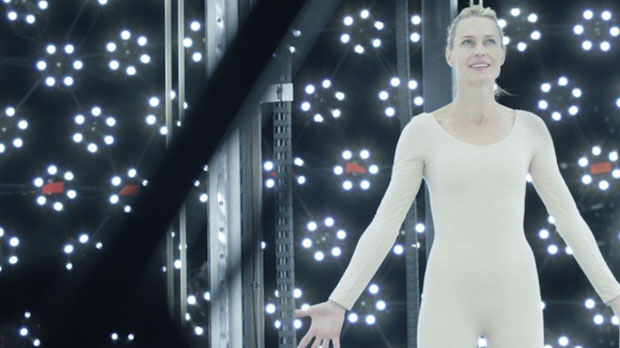

Jeff is sick of dealing with actors, their pettiness, their fickleness, and has found the solution: scan actors into a computer database to use their likeness in any way he sees fit. No longer acting in the real world, Wright’s computer image becomes a worldwide star once again, a household name as an android-killing action hero through a new type of cinema that is broadcast in the sky. Skip to 20 years later and Wright enters into a trippy animated world to renew her contract, this time giving up not only her image, but her entire essence.

Lem’s world comes alive in the latter half of the movie, in this scary futuristic world where people subsist on sniffing chemicals that allow them to forever hallucinate into whatever their heart desires: Michael Jackson, Grace Jones, or Robin Wright the robot-killer. They sell it as free will, but in reality these drugged-out citizens are poor and hungry zombies shuffling along inside of a broken alternate universe.

Folman’s film is vast in gorgeous detail, painfully hand-drawn animation that pays tribute to a century of classic cartoonists, and a wide range of themes that keeps the audience on its toes. His exploration of our obsessions with celebrity and aging ultimately look at how aware we really want to be of our own surroundings. If cinema is a form of escapism, Folman has created a new drug. The Congress is a film that must be watched several times to fully appreciate the multi-layered visuals and themes. Filmmaker sat down with Ari Folman in Cannes to discuss just how he put this incredible film together.

Filmmaker: The Congress was a gigantic undertaking. Was this film a lot harder to make than Waltz with Bashir?

Folman: It was tougher, 10 times tougher. With the European system, you have to spend the money where you raise it. So basically we had to do animation in nine different countries and then to manage the pipeline, and then to make the characters consistent. This was tough, very tough.

I would never do it this way again. I would finance the film differently and do the animation in two places and that’s it, not split the work.

Filmmaker: How did you arrive at the ideas behind the story?

Folman: I read the book when I was a teenager, and then I read it again in film school, and then after Waltz with Bashir, I wanted to do something that was not personal at all. The best escapism for me is sci-fi, so I went for the sci-fi stuff. And the second part of the film has a lot to do with the novel, obviously, and the first part is an introduction for the second part.

I got the story from different kinds of influences. I had the image of an aging actress whose films live forever and she’s forever young in the films, but in reality she’s just aging and aging and she has to face the fact that she’s [captured in stone] forever on celluloid. Then I started polishing these ideas and I came to the idea of the movie.

Every film you make, you close a circle in your life. I believe that doing what I am doing now, I close another circle and I know I have no clue what it is. You know I really don’t know, but one day I will wake up in the morning and it will flash lines that I will understand, where am I inside.

Filmmaker: Is scanning technology already here in the grand scheme of things?

Folman: This was shot in a scanning facility in L.A., completely. I didn’t know about it when I wrote the script. I had no clue. I was looking for an x-ray machine, and the scout told me, “Man we have it down the road, you know, in L.A. You can shoot there.” I think that technology is completely here, and they can do it. I don’t think they will, but I think it’s an option. And I think maybe in the case of a real economic crisis, the stock market, I mean if everything collapses and they need movies, they need entertainment, they will take it out of the drawer and say, “Okay this will cost us nine times less,” something like that, and they will do it.

And if I think about my kids, and I see the way they use technology in their life, everything is so natural for them. I say that in 15 years time, maybe they won’t give a damn if they see a movie and the character is a scanned character. I mean it’s good for video games, no? So what’s the problem with doing it in films? And if they need to have the celeb stars behind these characters, they will make a story, that his wife dumped him, and he’s in rehab now, and he’s depressed and who cares, you know?

Filmmaker: What for you makes a great story in cinema?

Folman: I think that we live in parallel universe, I hope it doesn’t sound too New Age-y, but no, I mean, we meet, we talk, but then our minds they go wherever they want to go. And I think a great movie, for me, the goal of filmmaking is to combine the conscious and subconscious and to make it into one. That once you go into the film, you just, you free your mind and for once, you go with what you see and you’re not complexed, you know? You’re not split anymore.

You’re in the journey. Your mind, it says, “OK, please, please give me rest, take me on that ride.” Your brain is completely disconnected from time, and the only time you see that exists is the time of the movie. This is it.

Filmmaker: What advice would you give to young filmmakers today?

Folman: I think it’s about persistence, like it always was. It’s about persistence and belief, the power of believing in what you’re doing, against the world a lot of the time. And originality. So not many people can be filmmakers. I mean sometimes technology makes you think that everybody can pick up an iPhone and make a feature length film, but they can’t.

It’s a language. I don’t see myself as an artist at all. I would never dare to call myself an artist. I like the word “craft.” I like the word “filmmaker.” I love it that it’s craftsmanship. I hope I know how to tell stories with picture and sound. This is craft, combining it together. If you do that, you’re fine.

And another suggestion I would have to young people is, forget about the auteur cinema. Forget about the guy who carries the burden: he has to be a writer, he has to be director, he has to raise the money for the project. This is bullshit, you know? You can be a great director and know nothing about writing. The only thing you need to know is how to work with a writer to make his scripts improve.