Back to selection

Back to selection

Appropriate Behavior and Obvious Child D.P. Chris Teague

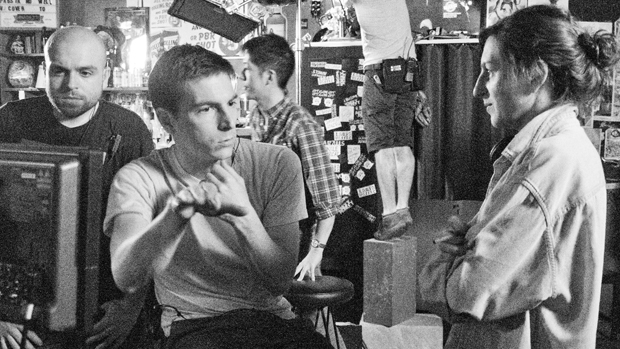

Chris Teague on the set of Obvious Child with director Gillian Robespierre and key grip Scott Sousa. (Photo: Danielle Lurie.)

Chris Teague on the set of Obvious Child with director Gillian Robespierre and key grip Scott Sousa. (Photo: Danielle Lurie.) In every young filmmaking scene, there are always one or two up-and-coming DPs you want to shoot your movie. These are the guys, or women, who have shot award-winning student films, who have loyal crews, and who know how to bring extra style, assurance and compositional smarts to first-time features. In the New York independent film community, Chris Teague has been one of those folks, and this year his talents are receiving greater recognition at Sundance, where two of his narrative feature films are debuting. In the Premiere section is the debut of Gillian Robespierre’s Obvious Child, a sly comedy about unplanned pregnancy starring 25 New Face actress and comedian Jenny Slate. And then in Next there is the debut of 25 New Face and co-creator of The Slope, Desiree Akhaven, Appropriate Behavior. The latter details the slightly absurd urban perambulations of an “ideal Persian daughter, politically correct bisexual and hip young Brooklynite.”

If Teague’s name is new to you, however, his work most likely isn’t — at least not if you’re a Filmmaker reader. Like I said, he’s the guy everyone has wanted to shoot their films, and, indeed, has been behind the camera of a number of acclaimed pictures by more 25 New Faces, including Myna Joseph (Man), Felipe Barbosa (Salt Kiss) and Tze Chun (Children of Invention). Below, he talks about working with first-time directors, why he likes to build his own lighting instruments and being a camera owner/operator.

Filmmaker: Let me start by asking you about the movies. You shot two films premiering at Sundance by two first-time feature filmmakers, both women. Both are New York-shot comedies realized on what I imagine were relatively low budgets. On paper, there would seem to be similarities between the movies, so tell us what’s different about them in terms of your approach and your work.

Teague: The differences in style probably come from the films that we were inspired by on each project. There was definitely some overlap — Woody Allen was a big influence on both films. We watched a lot of Annie Hall and Hannah and Her Sisters. Woody Allen was a real, direct influence on Gillian, but Desiree’s film has a little bit more of a handmade, “rough around the edges” [feel]. It’s very specific to her life, and Noah Baumbach was a big influence. We watched Margot at the Wedding and talked about that look. Both films, even though they are comedies, don’t necessarily have to look like what you might think a comedy should look like. You don’t have to see every character’s face all the time. Things don’t have be lit brightly; they can feel dramatic. Or you can do interesting things with the camera and still do things that are very funny. You can blur the lines between comedy and drama. And so, we tried to do that a lot, and in different ways.

Appropriate Behavior, I think is entirely handheld, and it feels very loose. We did a lot of preparation, but we really ended up making things up as we were shooting. Desiree is also the lead actress in the film, and so she really had her plate full in terms of hats to wear on set. She really trusted me a lot. She would get on set, block the scenes and then just focus on being an actor and let me take the lead on how we were going to approach covering the scenes with the camera. It was great to work with her because she had that trust in me. Which isn’t to say that she wasn’t involved in the visual look of the film, but she was very cool about listening to and respecting my input.

Filmmaker: Did you have relationships with either director before?

Teague: I didn’t, actually, no. Joey Carey at Sundial had sent me Obvious Child, and I read it as soon as he sent it. I just kind of fell in love with it and then sat down with Gillian and [producer] Liz [Holm] and we just really hit it off. It just felt like we were kind of all on the same page. Desiree I hadn’t met before either, but Desiree knew Liz, and Liz recommended me. And so, that kind of all came together right after we finished Obvious Child.

Filmmaker: We’ve been talking about these films as comedies, but were you thinking about them as being explicitly within that genre as you were shooting them?

Teague: I think so, but also, both of them are very dramatic and have very poignant, serious moments. In movies with both drama and comedy, I feel each element gets heightened in opposition of the other one, you know what I mean? There’s an interplay between the two that’s very powerful. I think it’s less about thinking of things as a comedy and more about thinking about how things work as a scene, what impact they should have, whether that is humor or sadness or just whatever feels right. It’s much more kind of instinctual than anything else.

The more I’ve shot, whether it’s comedy or drama or whatever, the more I’ve learned that it’s all about giving actors a place where they feel comfortable, where they can do their best work, because no matter how good the cinematography is, if it’s not well acted, then it’s never going to be a good movie. With Obvious Child, Jenny Slate is incredibly funny, and such a pro, Much of what we did was just give her room, covering scenes in a way that allowed her and Jake Lacy and all the other great comedians in the film to do what they do best, which is to play with and off each other. We tried to keep the scenes alive from take to take and not lock them into anything — to give them that freedom to work. That, to me, is equally important as the cinematography. I like to try to see myself as a facilitator of all the other elements of the film as well. I mean, I love collaboration. That’s the whole point of making movies, I think.

Filmmaker: What about in terms of the productions and the production demands? Were they similar in terms of the logistical issues? Or, were they very different?

Teague: I think they were similar. They’re both 18-day features. They’re both in New York. Obvious Child had a little bit more resources to work with, but you’re still struggling with the same situations, you know? Locations fall through at the last moment and then you’re scrambling to find a new location that fits the story [while] reconfiguring the way you visually conceived of everything. That just happens no matter what. Thinking on your feet is always going to come up. I think it’s just about going into it knowing you only have 18 days. You have to be as efficient as possible and not get yourself into a situation where you’re just running at a sprint to check shots off a shot list because that’s just not an environment where anybody can work creatively.

Filmmaker: When you came onto the projects, were there good 18 day schedules already in place and were you able to see how you could shoot the films within those? Or, was it a more complicated dialogue?

Teague: Making the schedule work is a huge part of making the movie work, and I like to be really closely involved in that. I had the same first AD on both films, Laura Klein, who was amazing, and we worked together really closely on both projects. It’s just such a puzzle to try to work out, and [that figuring out] is, for me, as much as part of cinematography as lighting or camera work. It’s using your resources as wisely as possible. Time is one of the most important resources so the schedule is hugely important, and it always changes.

Filmmaker: Were the adjustments that you had to make because of schedule, were they your adjustments in terms of you adjusting the way that you thought you might want to shoot the film? Or, were there more things that you went back to production on and were like, “You know, guys, we have to change this from night to day”?

Teague: There was a good example of that on Appropriate Behavior, where things changed for practical reasons that also, I think, helped the storytelling as well. There’s a scene in the film, a really intense argument between Desiree’s character and her girlfriend, played by Rebecca Henderson. We knew it was going to be a very heavy scene, we wanted to make sure we had the appropriate amount of time for it in the schedule, and we just couldn’t find a place to put it. It was scheduled to take place at night outside a bar, and I knew that doing a night exterior with a lot of dialogue was going to be time consuming and would involve a lot of relighting and logistics. And so I proposed that we shoot it at dawn instead. That way, we wouldn’t have to deal with any of the lighting requirements and we’d move very quickly. I think it really benefited the scene because the actors could stay in their performance and not have to stop every time we reset something or moved lights around. We blocked it so that we could shoot it from two different angles, and we just switched. Each take, we switched to the other angle. We went back and forth and back and forth so we could have some kind of lighting continuity over the time the sun rose from, I don’t know, five a.m. to 5:30. Desiree was really happy with it because it allowed her to work the way that she wanted to work.

Filmmaker: Did you use the same camera for both films?

Filmmaker: Yeah, both films we shot with a RED Scarlet, which is a camera I own with another cinematographer, Danny Vecchione. So, it was a camera I’m very familiar with and makes a great image. We also have a great set of vintage Cooke Panchro lenses, and they work against the sharpness of the digital cameras.

Filmmaker: What are you thoughts on being a cinematographer who’s also an owner/operator of the camera? In general, does it help, or sometimes do you feel that owning the camera influences you too much when it comes to format choice?

Teague: I think for the most part it is good to be an owner/operator because there have been many circumstances where the production could only afford to shoot with a certain camera, like a 7D. But, I own this camera and can find a rental fee that works for production. That benefits me because we get to work in a better format, and it benefits them because they get better production value. I think the only downside for me is that the Alexa is a camera I’ve used a few times and I love, but I hardly ever have a chance to get my hands on it because it’s just often so much more cost efficient for a production to work with my camera than renting a camera through a rental house. So, there is that whole concern of bias, but I do want to use the best camera for the circumstances. I’m shooting a microbudget feature in February, and we’re not going to use the RED because it’s just too cumbersome of a machine to deal with.

Filmmaker: What kind of lighting did you do on the films?

Teague: I did a fair amount of lighting on both films, but I hope you don’t really see it when you watch them. It’s all meant to be fairly invisible, as simple as possible. Obvious Child has a bit more of a composed feeling to it, both in the framing and the lighting, and, like I said, Appropriate Behavior’s a little bit rough around the edges, deliberately so. I was working with a tiny crew on both films, really great people I’ve worked with before who understand this level of production and understand how to maximize your time. As far as lighting goes, I realized this year that I don’t really buy into new lighting technology that much. A lot of people really love LEDs and stuff like that, but I get very nervous about using stuff that’s not totally proven yet. And the color, I’m not really excited about the color that [LED] creates. So I end up using a lot of homemade lighting instruments. I build a lot of stuff that just is lightweight — tungsten lights that are essentially a bulb, a socket, and maybe a piece of armature wire, so I can aim [the light] where I want to aim it. I can tape it to a wall and it goes up in 60 seconds and it’s cheap for production. I made boxes of lights like that and have lit entire bars with them. One of the bar scenes in Appropriate Behavior, we lit almost entirely with a 100-foot string of little string lights. I’m happy to simplify things because a lot of times when you simplify things, it just ends up looking better anyway.

Filmmaker: It’s funny, I’m sort of reading or hearing about more DPs these days just going with practicals or even no artificial lighting.

Teague: I think that’s kind of a dangerous path to go down because there’s no lighting and there’s “no lighting,” you know what I mean? I almost never just change the practicals in a room and just start shooting, unless that really, really works for the thing. There’s always something you do. The tricky thing when you embrace that [no lighting] aesthetic, in those locations where it doesn’t work, where it just doesn’t look good, you have to emulate that style of lighting, which can actually be really difficult to do. Like I said before, you’re trying to do something that feels completely invisible, as if there’s nothing added. There’s a lot of technique, I think, involved in making lighting feel invisible, or feel like you didn’t do anything, when usually, you did.

Filmmaker: What’s important for a first-time director to know going into his or her first film?

Teague: What’s important for a first time director to know is that there’s a thousand things that you could focus your attention on and you will only have time to focus on 100 of them. And so it’s about picking the best 100 things that you can focus your attention on. Going hand in hand with that is trusting your collaborators to keep their eye on those other things you just won’t have the time or energy to keep your eye on. And being open about the things that you’re afraid of, being open about your fears, I think is really important. When I start working with someone, hopefully we build a sense of trust together so I can understand from them the things that are making them nervous. Then I can do as much as I can to ease that burden on them, or take the flack in other areas, so they can focus their energy on the thing that’s really stressing them out. I mean, that’s what we’re there for. We’re there to support the director, and every director needs something different, you know? And that’s kind of our job, I think, to figure out what that is that they need.