Back to selection

Back to selection

Last Call for Heroes

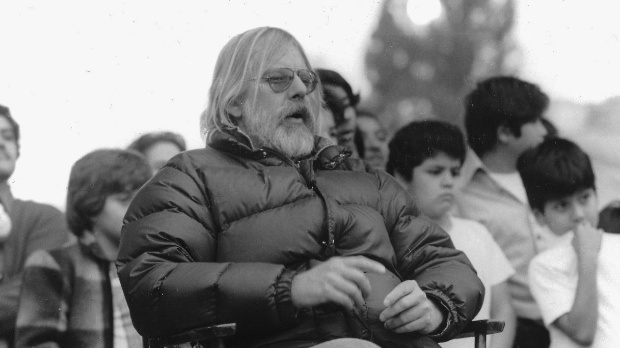

Hal Ashby

Hal Ashby I had a dream the other night, and all my filmmaking heroes were there. Young, full of vision, light in their eyes. A party at a swanky bar.

Then last call was called. And the lights came up. And Orson Welles was drunk, huge, exhausted. And Nicholas Ray, with an eye patch, was chain smoking. And Hal Ashby was haggard, mumbling to himself in the corner about someone taking away his final cut.

The horror stories of my heroes haunt me. What is it that happened to them? Did they bring it on themselves with youthful hubris and defiance? Were their movies too unique, too original? Were they really so difficult and impossible? Was it just the drugs and booze? Or were their downfalls caused by innocence, their naive artistic virtues, believing they could express themselves purely in the corrupted world of commerce. Maybe it was their stubborn idealism that launched the boomerang of vengeful studio men, men conspiring to humble their young charges into making generic cinema slop, conspiring to make them beg for finishing funds in obscure towns at the end of the earth. Maybe the big bosses were so scared of the blooming maestros that they started and spread rumors of insanity.

You go to the movies and the trailers are so oppressively repetitive, you don’t make it to the opening credits. You try to walk it off. A homeless man, long shaggy blondish white hair and beard, sleeps like a baby on Sunset. Hal Ashby had it smooth when everyone was on LSD. The movies he made then, like Being There, are unforgettable. But when the 80’s came, they took away his edits. Maybe the greatest editing director of them all, and they wouldn’t let him cut his own stuff. How’s that happen? And over and over again it happens. Sometimes it seems like the better someone is, the more the system will try to kill them. You put a dollar by the homeless man’s feet. You can only imagine how he got here, what talent he once possessed, what vision he once had.

Things are different now. Things are the same. You walk around Amoeba Records, go up to the dying DVD floor. You go through the director’s section: Francis Ford Coppola’s Jack sits right behind his Apocalypse Now. What happened? You see Scorsese’s shelf. Ever since he hooked up with DiCaprio, and big money, he makes movies of manufactured rebellion and irrelevant relevance. On the surface, they appear as maverick films, but they’re not. They don’t say anything. Not any more. Is Marty fading or have the studio men gotten to him too? Directors need a blood transfusion every so often, they need to reconfigure their very marrow, give up or reconstitute that enigmatic thing that made them who they once were.

Filmmakers don’t quit. Orson, Hal Ashby, Nick Ray. Coppola, Scorsese. Even when you wish they would. Maybe no one has a choice and it’s silly to think about all this the way you do. Maybe it’s out of the individual’s control. Old karma, too huge to comprehend. You don’t believe in fate, but fate never needed anyone’s belief.

What seemed punk and badass when you were younger now feels less glorious. Sickness and death come to all, why rush the process by banging your head against a heartless steel machine? How do you duck the machine and still make something new? How do you create without killing yourself? There’s less and less satisfaction in dissent. And yet, if there’s no resistance you know it’s not worth it. A popular and hollow party bag.

In the end, filmmakers need the belief of producers, investors, movie stars, agents, managers. They need help. It’s a vulnerable gig. If you’re a painter, you can go paint yourself into a corner. No guarantee anyone will show or buy your work, but you can still produce the paintings. Movies are different.

The cars speed by, and the weather is nice, and L.A. goes far in all directions. Endless dust, endless desire, until there’s desire no more. Last call. The faces of the masters are not saying to stop, but you hear that anyway. Don’t get caught in the quicksand. Don’t stick around for “just one more.” Get out of the movie thing while your legs are still under you and your f-a-c-u-l-t-i-e-s are still intact.

You wait outside the Arclight for your friend, a cinematographer named Yueni Zander. Yueni decided to sit through the feature. You watch people rushing in and out of the theater, talking on their cell phones. “How was the movie?” you ask Yueni, when she finally comes out.

“Oh I don’t know,” she says. “That was really 98 percent fresh on Rotten Tomatoes?”

“Yup.”

“Anyway, I’ve forgotten it already. Let’s blow this popsicle stand!”