Back to selection

Back to selection

The Death of Mr. Tarelkin: Edward Snowden on the Multi-Media Russian Stage

(Credit: Marina Ragozina)

(Credit: Marina Ragozina) Volunteers welcome you into the theater, guiding you towards your allotted place. The lights are going off slowly. As you sit down on your chair, you look ahead at the stage.

It’s unlike any other stage.

I was at the Culture Center ZIL in Moscow, attending a performance of The Death of Mr. Tarelkin, staged by the Manege/MediaArtLab Open School, Ballet Moscow Theatre and the International Centre for Dance and Performance TsEKh. This was a sidebar event at the 36th Moscow International Film Festival (June 19 – 28), described on the website as “a performance where Russian classics, contemporary dance, contemporary art and new technologies meet.”

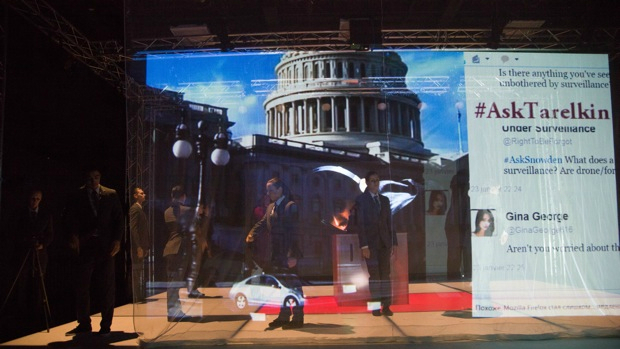

This logline doesn’t prepare me for the stage, which doesn’t have a single set. Instead, there’s a giant screen at the back, with the projector meant for it resting in front of the audience. A sheer curtain spreads out midway through the stage; it could serve as a screen for displaying projected visuals too. Two high-definition TVs are on mounts on either side of the stage; above them on the ceiling are two cameras, one for each, facing at the audience. “One can regard oneself a viewer,” the official description had ended by saying. “However, [bear] in mind that everyone is in the list of actors.” What?

The Death of Tarelkin is a play written in 1869 by Aleksandr Sukhovo-Kobylin, part of a trilogy titled Scenes from the Past that represents the author’s sole literary legacy. Sukhovo-Kobylin was a Russian aristocrat involved in a sensational murder case, arrested, prosecuted and tried for seven years for the murder of his mistress. Based on his experiences with Russian bureaucracy and the judicial system, he wrote these satirical plays, each an increasingly controversial success. Facing censorship problems, Tarelkin was first performed in 1899, 30 years after publication.

Sukhovo-Kobylin’s genius was soon recognized and his plays staged often. The first part of the trilogy, Krechinsky’s Wedding, became one of the most frequently performed plays in Russia at the time. One of the most iconic adaptations of his work was Vsevolod Meyerhold’s Tarelkin’s Death in 1922. On the Soviet side of the Revolution, tsarist dourness and rigidity could be laughed at. Meyerhold capitalized on this, depicting protagonist Tarelkin as a fool of bureaucracy, a cog in the red tape machine. With constructivist Varvara Stepanova, Meyerhold came up with a set of freestanding constructions made of wooden slats painted white. Each design was utilitarian and unspecific; different audiences inferred the scene to be a gymnasium, prison, or hospital, underlining Meyerhold’s point about the prevalence and uniformity of rottenness in society. He and Stepanova booby-trapped some set elements. This way, even the actors didn’t know what would happen to them once they sat on a piece of furniture; they might be tossed into the air by a spring in the seat or the chair might turn into a board. Sergei Eisenstein was a “laboratory assistant” for Meyerhold during this production; the time Eisenstein spent here informed his definition of mise-en-scène, something he considered an “attraction” in itself.

This latest performance sought to emulate Meyerhold’s revolutionary adaptation. In updating events to present day, the makers — Evgeniya Dolinina (idea) and Olga Lukyanova (direction) — wanted to change the evil of bureaucracy to that of surveillance. The protagonist is resurrected as someone resembling Edward Snowden. After all, national boundaries are increasingly obsolete; nowhere in the world can a person be guaranteed privacy.

The surveillance aspect explains the cameras facing the audience. How they react or feel looking at projections of their own faces was a vital part of the performance. The multiple screens around the stage are all outlets for the screens the characters are interacting with while on-stage. When the protagonist opens the lid of his laptop, whatever he does fills up the screen at the back of the stage. The sheer curtain is pulled across the stage during an interval; it displays news reports and headlines supposedly advancing the story.

It’s a novel experience, sure, and not irrelevant to the subject or theme, but it didn’t transcend the feel of a gimmick. Because of how sporadically and disjointedly the shifting media and multiple screens were implemented, it jarred each time they intruded. My favourite moment from the whole evening began with the empty and dark stage. The TVs on either side soon lit up with footage of armed forces nearing a building. As soon as they reached the entrance, the stage between the screens lit up and performers dressed up as the armed forces continued this invasion in person. The fluidity and neatness of the transition blindsided me.

It’s undeniable that increasing the number of moving parts and transitions in the performance would raise its complexity exponentially, to possibly unmanageable levels. However, when exploring new territory like this, doing so in a half-baked manner doesn’t impress anyone. Substantial stretches didn’t use any screen or rested on just one element, such as dance. Hopefully, the organizers of the performance or other such groups across the world can take inspiration from this effort and dive deeper. An enthralling multimedia work of art awaits on the other side.