Back to selection

Back to selection

“Makin’ Your Own Rules”: Ron Mann’s Altman

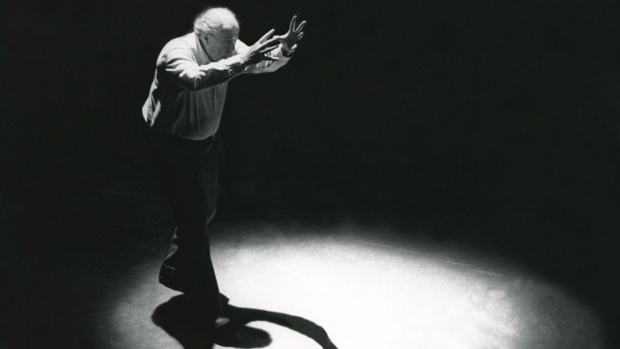

Robert Altman (Photo courtesy of Sandcastle 5)

Robert Altman (Photo courtesy of Sandcastle 5) Altmanesque.

Ron Mann asked a dozen admirers to define that term in Altman, his new documentary about the director of *M*A*S*H, McCabe & Mrs. Miller, The Player, Gosford Park and 40 other features spanning an astonishing five decades. “Inspiration,” Paul Thomas Anderson answered unsurprisingly. “Creating a family,” Lily Tomlin offered. “Makin’ your own rules” was James Caan’s definition.

Mann’s portrait of Robert Altman is exciting and eloquent but nearly too reverential, more a tribute than a biography. The capacity audience at Toronto’s TIFF Bell Lightbox Friday night didn’t need reminding of Altman’s greatness. The Canadian premiere of Altman kicked off a retrospective that will include cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond introducing a screening of McCabe and Mrs. Miller.

“One big reason I made this movie,” Mann told Filmmaker, “was to remind people that there’s an alternative to today’s comic book movies.” Altman details how the maverick director followed his own path, publicly clashing with studio heads, and never compromising on any of his films until his death in 2006. What set Altman apart were his intense collaborations with ensemble casts, similar to a director on a theater production (he helmed several in the ’80s) where actors can freely improvise. Pity there isn’t a rehearsal or outtake in the doc showing this process. Another definition of “Altmanesque” might be the director’s revolutionary use of overlapping dialogue, though Altman includes a harsh TV review of Popeye criticizing the perceived excesses of this technique.

What emerges from Altman is an artist bold enough to take chances in a conservative art form. Though he never met his hero, Mann admired Altman’s work ever since he snuck in as a 12-year-old to catch the R-rated M*A*S*H in 1970, which injected a harsh reality into American comedy and cinema, something that grabbed Mann. “I saw Bob as a counterculture filmmaker form the very start,” Mann explained to his hometown audience.

What really sparked the Toronto documentarian — renowned for his takes on pop culture including The Twist, Grass and Go Further — was Mitchell Zuckoff’s superb 2009 oral biography, Robert Altman. As soon as Mann finished it, he phoned the writer, who instructed him to get Kathryn Altman on board. By chance or serendipity, she was attending an Altman retrospective at the Torino Film Festival that same week in December 2011, and Mann went. Altman producer and jazz fan Matthew Seig admired Mann’s 1981 jazz doc Imagine The Sound and recommended to Kathryn that she have lunch with the director. After screening Mann’s docs, she gave the Toronto documentarian her blessing. She and Seig wound up as consultants on Altman.

Mann swiftly raised the budget, and his luck continued when he plumbed the Altman archives at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. “Picture the last scene in Raiders of the Lost Ark with all those boxes,” Mann recalled. Instead of the one week planned, he spent six weeks poring through hundreds of thousands of photographs to curate 15,000. The research paid off with excerpts from two unreleased short films, a surreal romp depicting a house party and an unabashed valentine to the joys of pot-smoking. Mann also unearthed an original Altman score for a never-produced musical from the fifties; one song, “Let’s Begin Again,” plays at the end.

In addition to the Michigan archives, Mann also secured access to Kathryn’s own personal archives (which will be excerpted in a tie-in book to be released this fall). She also offered 150 home movies that were gathering dust in a Los Angeles storage locker. Though they aren’t revelatory, the private footage offers candid glimpses of Altman directing actors on M*A*S*H or Images, or showing a lighthearted side to the director such as when moving to Paris in 1985. I only wish there was more of this footage.

“Kathryn insisted on complete autonomy for me,” the director stated, “because Bob demanded autonomy on his films.” Even so, Altman softens the jagged edges around a complex personality. According to Zuckoff’s book, Altman was generous to friends but could be cruel, especially when drinking. Altman collaborated on his sets like no other director but could be tyrannical like so many. Furthermore, Altman’s battles with studio heads illustrated his pathological hatred for authority, which he wore as a badge of honor, but which also made him unnecessarily reckless.

Whereas Zuckoff’s book is a Rashomon-style warts-and-all portrait of told by dozens of voices, Mann’s biodoc is largely narrated by Altman, Kathryn and their children. At times, it’s frustrating that the dozen actors who appear in the film — including Sally Kellerman, Bruce Willis and Michael Murphy — utter only their definition of Altmanesque without offering anecdotes about working with a director who revered actors.

“Everyone I met on this film had a Robert Altman story,” Mann said. After seeing the archives from the university and especially the family, he decided to try a personal approach and tell his film through their eyes. In this respect, Altman resembles Stanley Kubrick: A Life in Pictures — another fine film doc, but also sanctioned by the filmmaker’s family and limited by it, whether directly or indirectly. Does this ruin Altman? Not at all. Altman is an absorbing, marvellous film that manages to squeeze a wildly prolific career into 90 minutes and paint a portrait of a true original.

So, what’s Ron Mann’s definition of Altmanesque? He pauses in contemplation and answers: “Heroic, independent filmmaking.”