Back to selection

Back to selection

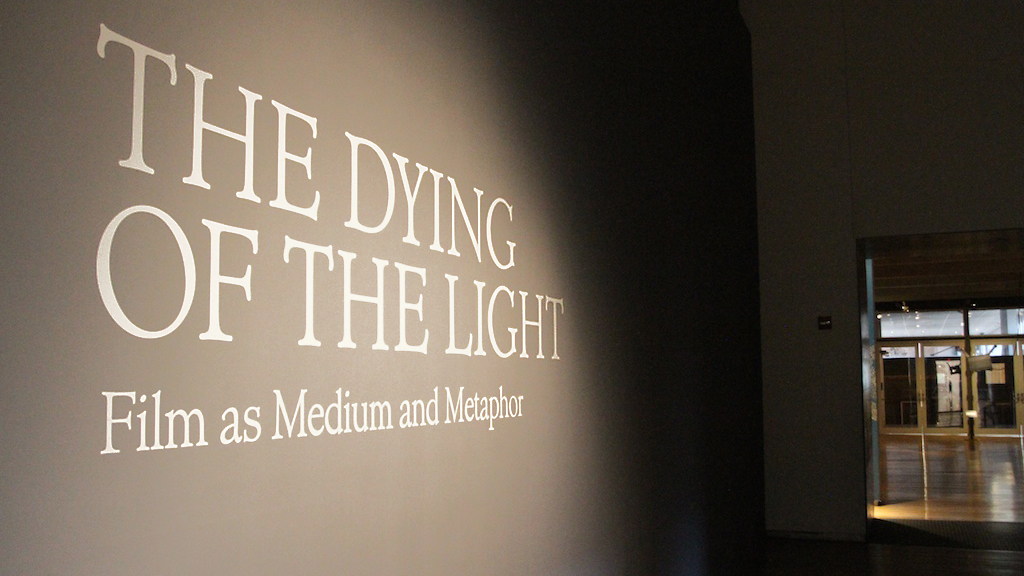

“Dying of the Light” at MASS MoCA

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

– Dylan Thomas

If you’re anywhere near North Adams in the northwest corner of Massachusetts, close by the New York and Vermont borders, anytime between now and February 1, 2015, do yourself a favor and drop by the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art to contemplate their exhibition marking the last days of photochemical motion pictures: The Dying of the Light: Film as Medium and Metaphor.

With the contraction of film manufacturing and virtual demise of laboratory services in the face of near-universal digital imaging, the medium of perforated, emulsion-coated film base — after a spectacular hundred-year run — is slipping into the special province of archives and museums, institutions that safeguard the past.

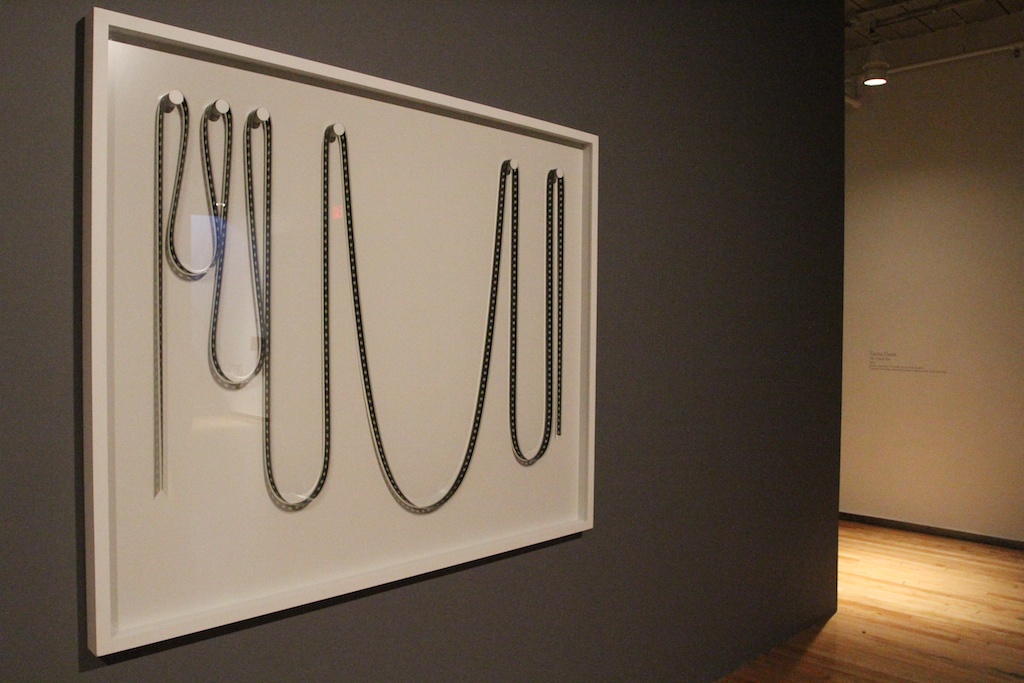

MASS MoCA however has taken a step to protect the future, gathering the work of six artists — Rosa Barba, Matthew Buckingham, Tacita Dean, Rodney Graham, Lisa Oppenheim, and Simon Starling — each a passionate advocate for the survival of light-sensitive film as a living medium “for its distinctive grain, texture, and luminosity — as well as its potent potential for metaphor,” to quote MASS MoCA’s exhibition notes.

Quoting further: “In a mix of atmospheric, sculptural, and documentary works, the exhibition includes a selection of rather pared-down, but powerful images – fire, smoke, the setting sun, a spinning chandelier, a racetrack, figures in motion, and the transit of Venus — all nods to the most essential elements of film itself – light, movement, and time.”

What you’ll experience at this MASS MoCA exhibition are cavernous, formerly industrial spaces devoted to unattended 16mm and 35mm projectors whirring and clattering as they project ceaseless film loops against walls and suspended screens. You may find yourself alone in an installation space – for as long as you’d like, just you and a projector – a perk of MASS MoCA’s sheer size that, unintentional or not, nonetheless privileges the act of private experience. It’s like having your own screening room for art.

Where did all this installation space come from? It may come as news, but MASS MoCA is the largest contemporary art museum in the U.S., with twenty-six interconnected buildings covering thirteen acres.

Before MASS MoCA opened in 1999, North Adams was a depopulated former mill town on the Hoosic River named for Revolutionary patriot Sam Adams, namesake of the popular beer. Its central red-brick factory complex, which had sprung up before the Civil War to make printed textiles, was shuttered and decaying. The textile business had succumbed to the Great Depression, and the subsequent occupant, Sprague Electric Company, renown for electronic components, had hit the skids in 1985. Fortunately for North Adams, the former factory’s sprawling network of handsome industrial outbuildings and endless supply of large, well-lit, open interiors proved the perfect fit for a world-class center of contemporary art.

In fact, one entire building is now given over to a monumental retrospective of the life’s work of conceptualist Sol LeWitt – on view through 2033. Is it too much to hope that The Dying of the Light: Film as Medium and Metaphor might one day inspire a more permanent installation – perhaps fill an entire building – dedicated to the living, flickering light of the motion picture projector?

Metaphorically, an eternal flame arc lamp?

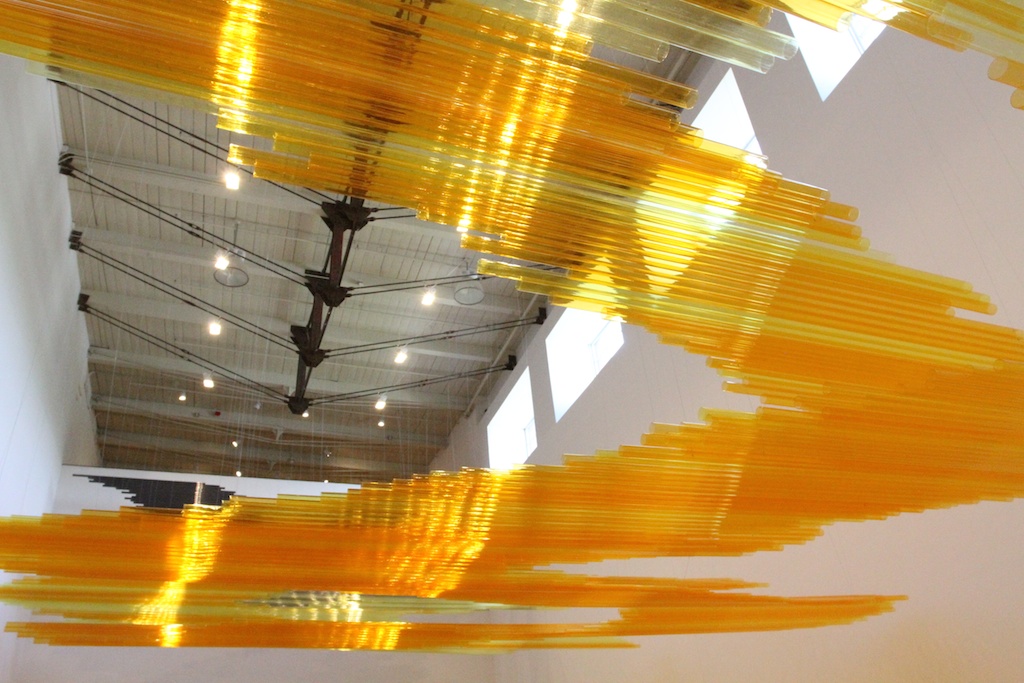

P.S. When visiting MASS MoCA, don’t miss Teresita Fernández’s show, “As Above So Below,” through April 5, 2015, in particular a work called “Black Sun,” which, title aside, looks like an enormous argyle-shaped raft of translucent orange, yellow, and gray reeds floating above your head. Who knew gel tubes for fluorescents could be put to such transcendent use?