Back to selection

Back to selection

Barbara Bancaccio And Josh Zeman, Cropsey

Part personal history remembrance, part time capsule of a place, part true crime thriller, Cropsey is an absorbing and terrifying piece of filmmaking. A rough hewn, nine years in the making feature directorial debut for narrative film producer turned documentarian Joshua Zeman and NYC Human Resources Administration’s Deputy Commissioner Barbara Brancaccio, it delves into the disappearances of several handicapped children in their native borough of Staten Island during the ’70s and ’80s. The filmmaker trace their distinctive childhood memories of the events as well as those of dozens of Staten Island residents who live on with this disturbing mystery, many unconvinced—even though someone has been brought to justice for these crimes—that the book is closed on these terrifying events.

In 1987, a so-called “shadowy drifter” named Andre Rand, an occasionally homeless man and former convicted child abuser who had worked at (and lived in the woods behind) a notoriously inhumane children’s mental institution in the borough, was charged with the kidnapping and murder of Jennifer Schweiger. A 13-year-old with Down Syndrome who disappeared that year, Schweiger was later found half buried in the woods near the Willowbrook Mental Institution, Rand’s former workplace. Convicted only of the kidnapping, it became apparent over several years that Rand was implicated in the disappearances of a rash of disabled children during the previous decade and a half. Or is he?

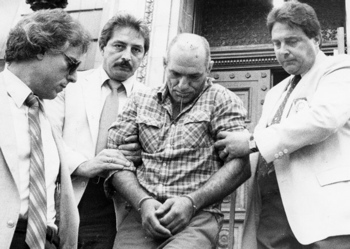

All the evidence is circumstantial. A few people who the filmmakers encounter doubt that he committed the crimes. Rand refuses to be interviewed and has already been largely demonized by the public at large, mostly due to the deranged photos taken of him as he was led out of a police precinct, drooling, in 1987, when he was first booked. Eventually, as Zeman and Brancaccio attempt to reach out to Rand for answers, he begins writing back to them. The increasingly strange correspondences, which universally maintain his innocence, draw Zeman and Brancaccio even further into the case as he’s brought to trial for another young girl’s 1981 disappearance as his first sentence is drawing to a close.

Cropsey will be available via Video on Demand June 2nd. It opens in Manhattan at the IFC Center on June 4th.

Filmmaker: This is obviously a very personal project. Perhaps more personal then some of the films you’ve worked on a a producer, Josh.

Zeman: It is a little bit different, a little bit more personal. Ultimately, the right tone of the film was pulling back on some of the personal elements a bit. The right tone was to come at it as journalists with a personal connection, rather than presenting the personal connection and then the journalistic angle second.

Filmmaker: Was separating the two troublesome at all?

Zeman: It wasn’t troublesome, but there was some fine tuning to do. I think that was really the issue and its that way with every doc, finding the tone that really speaks to the audience. Unfortunately, when making docs that have a personal slant, finding that tone is alittle bit more difficult.

Filmmaker: The film skates the line between personal relevance and crime reportage really well.

Zeman: That’s the hardest part I think. I have a journalism degree. One of the things that always interests me as a storyteller is the person who tries to be as objective as possible but can’t help but get caught up in the subject emotionally. I think that that’s really cool.

Filmmaker: How did the two of you meet? When did you decide to work on this project together?

Brancaccio: Kindergarten. [laughs] Right now. [laughs] no, no…

Zeman: Practically. We didn’t know each other from Staten Island. We met later in life. We were both living in Manhattan. The first conversation we had was, “Oh you’re from Staten Island, I’m from Staten island! Do you remember the Jennifer Schweiger story and Andre Rand?” Then we started to go on a hike back to Staten Island. We were like, “oh yeah, lets go back and check it out!” It’ll be this sort of fun thing to do. We went back to Staten Island and we were hiking through the woods that run around Willowbrook and in the middle of the woods was a rusted out tricycle and an abandoned playground. There’s like this rusted merry-go-round with a tree growing through it that you see in the film. So we had been talking and reminiscing about Jennifer Schweiger and Andre Rand and the whole thing that happened in the Willowbrook mental institution and we went back and everything in the woods was still there, nothing had changed in twenty years since we had left Staten Island.

So we got back from our little trip and about a week later the district attorney announced that he was indicting Andre Rand for the disappearance of Holly Ann Hughes. Suddenly we were like, “oh my God, we have to use this opportunity! We now have a reason to tell this story from our childhood.” We were asking, why now? Why are you going to tell this story now? Well, the indictment afforded us the opportunity to go back and tell the story.

Filmmaker: Where did you start your journey into Andre Rands world? When did he personally become aware that you were making the film?

Brancaccio: The story began in Willowbrook and those areas in the central part of the Island and the woods, they became a central character to the story we were telling immediately. We started going through news clippings and whatever information we could find on the story, including people’s names, and then we just started calling people. At first we met with the friends of Jennifer folks because they seemed the most obvious, the most public, then we reached out to family members and then finally we just wrote Andre Rand a letter. That’s pretty much how we started. Josh is right that the indictment was really what sparked it. We were telling each other the story and were definitely interested in the urban legend piece or it and the mystery of those missing children no question. From the beginning, we felt there was some link between the urban legend and those children disappearing, but it wasn’t happening yet and then the indictment happened and that proved to be the springboard and we started. It seemed that each person introduced us to another person involved with the story. Staten Island is a borough in New York, but it has a very small town feel.

Zeman: And mentality.

Filmmaker: I think that comes through in the film.

Brancaccio: Even between Josh and I its funny, we met at sort of a neighborhood place where we had mutual friends and our first conversation being what it was, but almost immediately it becomes about remember this, do you know this, because the truth is we’re the same age, we had been to all of the same places, and probably in the same places at the same time on a number of different occasions. In interviewing the people, we picked up on how there’s maybe one degree of separation between us and the subjects often times. So it was very quick from the time we showed interest to the time that we started. By the time Rand got back to us, it had been a longer period of time. Maybe a year.

Filmmaker: How long did the film take to complete from start to finish?

Zeman: Nine years.

Brancaccio: From conception to the day we saw it on the screen at the Tribeca Film Festival, it was nine years.

Zeman: I mean, that was work. I produced four movies in between, so it wasn’t constant, but I think we needed that time to come to terms with the story, with the philosophy, to really comprehend and be able to understand and recapitulate the urban legend ideas that would put forward in the film. Only when we began to have subsequent conversation with folklore experts did we really understand what we were talking about.

Brancaccio: Exploring the kind of storytelling that we were engaged in, having an instinct for the way you want to tell a story, then embracing it, it took some time for that. We thought that maybe we were onto something and the more you talk to people, it just started to form itself organically, but over a long period of time.

Zeman: We weren’t just making a documentary with a story. We were making a documentary with a story and that was just one level of the onion. The second level of the onion was, lets talk about the making of the documentary about this story for a larger, contextual, anthropological storytelling sense. To have that dissertation about what we’re doing, we needed that time to give us the perspective to come back and look at it through the looking glass.

Brancaccio: I don’t want you to think it was all this navel gazing. It wasn’t. [laughs] We both had other jobs. Josh was producing other films. I work for the city. We had to make money. We had to gain the trust of the people we were trying to interview. We had been calling some people who embrace us and love us now, but it was bordering on stalking their for awhile. We were young. Some people were like, “we have to let these kids come over or else they’ll never stop calling us.” So you understand. Now we look back and talk about the process of making the film, but part of the process of making the film was getting people to talk to us.

Zeman: We did it on weekends. It was like a weekend film for years. We both had jobs.

Filmmaker: Did your opinion about Andre Rand’s guilt or innocence change while making the film?

Brancaccio: Yes and no. Everytime we went out there… We’ll yes. We switched opinions about it several times, but ultimately I still think what I thought about it at the beginning and he still thinks what he thought about it from the beginning so-

Zeman: We both thought very different things and I think that allowed us to be objective. When you have two sides of the story and you’re being subjective with both, it allowed objectivity to come in. We were always forced to let the other one talk, to let the other side have its say. There would be a fight, so we couldn’t not do that, you know? [laughs] Then weirdly enough, in the middle, it switched. I thought one way and she thought another and then our opinions reversed. Then it went back again. I think that really helped, it helped us see both sides of the story.

Andre Rand is a smart guy. When you get letters that quote the legal system, that don’t reveal the raving lunatic that people purport him to be, as a journalist you have to go in and say, “I’m going to give this guy the benefit of innocent until proven guilty.”

Brancaccio: Or maybe he’s just a good jailhouse lawyer. The thing I find the least… clever is that only he knows the answers to these questions he’s been asked repeatedly.

Zeman: So wait a second. Are you saying you think you believe now what you believed in the beginning? [laughs]

Brancaccio: I think that I shouldn’t have to tell people what I think because I’m the filmmaker. I should be able to stand behind it. I think what we try to show in the film is that he was convicted of kidnapping, not of murder, and as you see in the film, there is a very limited amount of evidence. I think the most compelling point that we’re trying to make is that every single person on that island believes that he’s guilty. I don’t exactly know why. I think its because he’s this manifestation of everyone’s fears and anxieties. That’s over here. On the other side, there is an actual trial, where there’s evidence and twelve people unanimously found him guilty. We’re not disputing that he was in the vacinity of every one of these children at the time of their disappearance and they were able to prove that. So that’s one reality. Another reality is that you ask someone in Staten Island about Andre Rand and they say, “oh, he’s a pedophile, oh he’s a serial killer, an axe murderer, the boogeyman of Staten Island, he’s a necrophiliac, he’s a homocidal maniac-

Filmmaker: Everyone has their own version of it.

Zeman: Exactly.

Filmmaker: When does perception trump reality?

Brancaccio: We always thought of it as a little urban legend, this axe wielding boogeyman for little kids.

Zeman: Almost an innocuous one. Then it became-

Brancaccio: Real scary.

Zeman: An adult urban legend. Which is devil worshipping, child pornography, cult activity-

Brancaccio: Selling children, sex slavery-

Zeman: Then it became, not just the stuff of nightmares, but actually warehousing children, as you actually see in the movie. Our fears actually morphed from one to the other. In the end, I come back to the idea that Andre Rand was in some way the collective scapegoat for Willowbrook. Its an urban legend borne of urban politics.

Filmmaker: At one point you’re interviewing a district attorney and he refers to Staten Island as New York City’s dumping ground. I found that so memorable, the place where you put things you don’t want to see anymore.

Zeman: You mix that pot up, double, double, boil and trouble. Out of that is going to come a Frankenstein, a collection of all of our fears, but doing it from a messiah standpoint, claiming to try to save children, because of the stuff that he witnessed. As a human being, I think I would snap if I witnessed first hand what was going on at Willowbrook. I can’t even imagine what that would put me through. So when we do those things, we have to expect that its going to manifest itself in some way, shape or form. Is it going to be the man who walks in and starts blowing people away with the semi-automatic a la Columbine, or is it going to be the man who thinks he’s doing God’s work by “helping” children.

Brancaccio: Josh obviously has a very expanded view on Andre Rand’s “messiah” complex. [laughs] Its difficult to put into the movie, but if you want to know about it-

Filmmaker: DVD extras material.

Zeman: I’m sorry to go on about it, I just have to believe that there’s the child urban legend and then there’s the adult urban legend, there’s the kid reason, the fanboys who love all that serial killing stuff and then its like, no, it’s something much more poisonous.

Brancaccio: One of the urban legends is that he was picking children who were disabled because he was saving them on God’s behalf, saving them from families that didn’t want them.

Zeman: His mother had been in a mental institution. That’s very clear in the film.

Brancaccio: It is clear in the film. I’m not teasing you in that way. I think that that’s one of the various possibilities. That’s in the pot as well. Some people say that he didn’t act alone, that he was something of a pied piper and led this ring in the woods-

Zeman: He was leading a group of homeless, mentally disabled people in the woods.

Filmmaker: You can project onto him almost anything that you’d like to.

Zeman: Really what it was, and this is hinted at in the movie, is that you had alot of Irish, Italian and Jewish immigrants leaving the city. When the Verrazano was built, they went over to Staten Island, and they struggled for so long to get a semblance of middle class life. So when you lived in the city and there’s an abandoned lot, what happened in that abandoned lot? Nothing good. You got beat up. When you came home from school, you take the shortcut, you got raped [laughs], so suddenly, all these people who have this fear of abandoned lots, of the little bit of green, mysterious woods, they get out to Staten Island, and there’s this huge expanse of woods. Oh my God, what’s happening in there? They’re freaking out. They’re like, I finally got this beautiful house and this lawn and out beyond my lawn in these woods is a mental institution-

Filmmaker: Like true paranoid New Yorkers, they can’t just see it as rustic beauty [laughs]

Zeman: Of course. [laughs] Not only that, its not just that there were chirping birds and bambis, but there really were abandoned buildings there with history. So it wasn’t just fear, it was fear with alittle historical and cultural precedent to it. So when these kids start to disappear, it wasn’t just “oh my God, there’s this guy in the woods”, but social anxiety, social guilt for moving up from lower to higher. Same thing happened on Long Island. Look at Capturing the Friedmans. Suddenly you move to Great Neck and suddenly you’re children are being-

Brancaccio: Molested by the math teacher-

Zeman: Molested by the math teacher! But within the response to that is some status anxiety.