Back to selection

Back to selection

A Matter of Semitics: A Borrowed Identity

Tawfeek Barhum in A Borrowed Identity

Tawfeek Barhum in A Borrowed Identity What’s in a name? Labeling is a risky proposition. Meant to attract, summarize, or simplify, sometimes all three, a tag’s position front-and-center makes it bait for bashing. Pigeonholing can repel as easily as it entices, or just may harmlessly connote something other than what was intended. In the cultural arena, a title can be artwork-specific and subject-appropriate, only to be slammed, censored, and overruled by the poison of protocol or more overt political and commercial censorship. In theory merely a signifier, it frequently serves as a convenient synecdoche for larger issues under hypocritical attack.

Which brings us to Dancing Arabs, the latest film by Israeli vet Eran Riklis (The Syrian Bride, Lemon Tree, The Human Resources Manager), being released stateside as A Borrowed Identity — a half-assed and misleading moniker for an otherwise marvelously balanced film: thoughtful, thought-out, and gracefully fluid. More a meticulous than an intrusive director, he does throw us some powerfully sensuous bones. Take the night scenes of the lit Old City of Jerusalem, with which he brackets the film, and overhead shots just low enough to grab remarkable textured details in underrepresented sites like the manicured Muslim cemetery of such affective narrative significance we visit it not once but twice.

The original Hebrew title is taken from the autobiographical novel by the well-known, controversial Israeli Arab journalist Sayed Kashua (currently teaching in Illinois, he has sworn never to return to Israel), who also wrote the screenplay. The innocuous expression “dancing at two weddings” refers to the frustrating, seemingly irresolvable conflicts facing Israeli Arabs trying to reconcile Arab ethnicity with Israeli nationality.

The film was slotted to open last year’s Jerusalem Film Festival, but yanked from the coveted spot to a less desirable position just days before the event began. Israel was entering Gaza. Citing security issues, the programmers got touchy about offending Arabs — not with the film but with its name. A movie recounting the experience of one Palestinian teen attending an upscale, otherwise all-Jewish college in Jerusalem in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, only in the margins does it touch, and lightly so, the greater Palestinian-Israeli conflict. There is no violence. Nobody throws bombs.

Jews, in fact, are the only aggressors, and just in a few scenes do students and soldiers harass, without recourse to force, the somewhat overdeterminedly angelic Palestinian protagonist, Eyad (Tawfeek Barhum), a model Israeli Arab citizen, son, student, and friend. He is hardly a provocateur: only in a single scene, powerful and poignant as it is, does he question Israeli hegemony. It is phrased in a politely-delivered classroom monologue on how Israeli novelists sustain the stereotype of the “stinking” Arab male, a sexual predator targeting Jewish women.

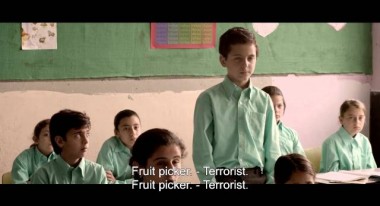

To underscore the excision of violence, Riklis injects for contrast the saga of Salah (Ali Suliman), Eyad’s blue-collar father, a former militant expelled from university in 1969 after a two-and-a-half year detention for possible involvement in a bombing that ruined any chance of professional placement. “We thought we could liberate the Palestinians from the Jews,” he tells his son. “Now we just want them to leave us alone.” In another example of the bottled-up danger in labels, in the early section of the film, a young Eyad argues the nature of his father’s vocation with the quasi-collaborationist principal in his hometown grade school. “Terrorist!” insists the boy. “Fruit picker!” the teacher responds. The bout continues, ending with a triple slap that nearly breaks a twig but not Eyad’s will. The stubbornness and drive will come in handy after he grows out of the Palestinian schools and leaves home to study at the Hebrew-centric Jerusalem Art and Science Academy.

Israel is not the only paranoid territory troubled by the branding of Dancing Arabs. Worldwide, only Canada has retained the original title. Otherwise, My Son, My Sons, My Heart Dances, and of course A Borrowed Identity. The troubling word, of course, is Arabs. Where is the insult? How do Israeli Jews regard the title? Riklis recalls in an interview that when he told a taxi driver the name of his movie, the fellow’s response was, “Well, if they’re dancing, I’m not worried.”

At the beginning of the film, text appears with prose from the late, eminent Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish: “Identity is…our invention and not our memory.” The words are key to the overriding theme of A Borrowed Identity, and probably the principle divisive factor in Israel as well: the categorization of Jew and Arab. In its own way, the movie assesses the process of labeling, the possibility of unloading associated baggage, and the consequences of taking action, what is lost and what is gained.

Class distinctions are present but more covert. The two Jewish families in the film are middle to upper-middle-class, owners of elegant, spacious homes open to the world outside, the school itself an institutional echo of their privilege. Eyad’s large, extended Palestinian family lives in cramped quarters in a one-story stucco house. Riklis does not leave the difference at the level of materialism. The Jewish residences are cold; there is a lot of empty space between characters. In the modest Palestinian home, the close physical proximity of family members creates warmth and intimacy, even when internal ideological and cultural gaps surface.

In brief, here is the overall storyline: Seventeen-year-old Eyad is a pretty boy genius whose acceptance to the prestigious school marks, for his father anyway, a comeback. Adjusting to a new milieu involves the usual shocks of adjustment, like adapting to a new (here essentially foreign) set of schoolmates. Not just a promising student, he shows a knack for entrepreneurship, starting a hummus business on campus.

Two blossoming relationships with fellow Jewish students alter far more than the course of his education. He and the beautiful, vivacious Naomi (Danielle Kitzis) begin a secret, illicit affair, often meeting backstage in the school theater — a back-of-the-bus romance. He’s not the smelly wolf he finds in the books he deconstructs for the other students, but this Ashkenazic jewel is forbidden fruit, so a vague connection with the generic Arab men is implied. Eyad keeps the relationship from his parents, but once his mother hears him on the phone with Naomi, she becomes supportive. After Naomi tells her parents, they make her withdraw from the school. Eyad offers to quit so that she can return; she accepts his sacrifice. As likable as she is in some ways, she becomes pushier and more selfish. Even after his dad throws him out of the family home for abandoning his own goals, and Eyad has to wash dishes in an East Jerusalem eatery to survive, she continues to thwart his efforts to make the relationship viable in order to advance her career.

The Eyad-Naomi romance plays second fiddle to the darker, more serious bond that develops between Eyad and Jonathan (Michael Moshonov), a schoolmate who suffers from lifelong muscular dystrophy, and whom Eyad volunteers to tutor at his home. On the sidelines, but of great significance in the climax and resolution of the film, is Jonathan’s stunning and stoic widowed mother, Edna (Yael Abekassis), who appears to be a lawyer and is as resolute and noble as Eyad, with whom she builds a committed platonic relationship. Jonathan and Eyad learn to truly love each other, forging a connection through black humor (nothing is sacred, especially references to Jews and Arabs) and alt music. Eyad does not remain only a tutor: After becoming Jonathan’s best friend and his condition worsens, he also serves as nurse, nurse’s aide, and pipeline to the outside world.

I do not want to say too much about the remainder of A Borrowed Identity. It so poetically and righteously addresses the topic of the subjectivity and oppressive potential of human labels, and Riklis and Kashua so expertly tool the concept of a borrowed identity in this unique narrative. But you can put two and two together. The U.S. title suggests a swap. Jonathan has a terminal illness; Eyad has major hurdles in his path, at school and in the workplace. The rapport between Edna and Eyad blossoms further. What I’ll reveal is that substitution replaces coexistence as a cure for the Israeli-Palestinian impasse.

In an insightful essay in the journal Fathom, Gabriel Noah Brahm envisions the quagmire as universal:

(The film blurs) the line between self and other, public and private, I and thou, personal and political, essence and existence—challenging audiences to ask themselves who they think they are, to check and see if they really know so well after all.

The film deserves to be judged on its considerable merits. Festival selectors and distributors busting Riklis’s balls on account of a title, especially one true to its source? Do outside events actually matter? They should just leave things be. They should react to circumstances just as Eyad himself does in the movie:

Makin’ the best of a bad situation

Don’t wanta make waves, can’t you see.