Back to selection

Back to selection

NYFF Critics’ Notebook: The Sky Trembles and The Earth is Afraid and the Two Eyes are Not Brothers

The Sky Trembles and the Earth is Afraid and the Two Eyes are Not Brothers

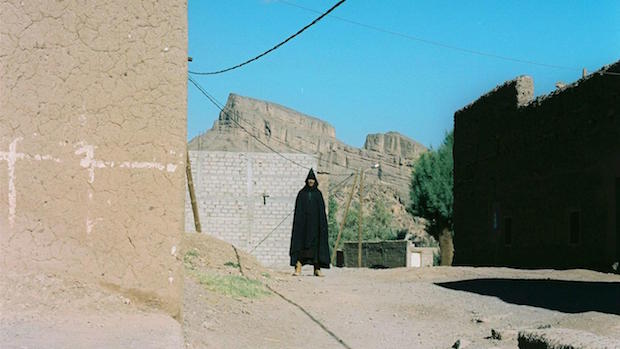

The Sky Trembles and the Earth is Afraid and the Two Eyes are Not Brothers The Sky Trembles and The Earth Is Afraid and the Two Eyes are Not Brothers (you can memorize the title after reciting it enough times — don’t fret) opens with a small fleet of ’80s Mercedes-Benz coupes, trailed by dune buggies, speeding across a desert. A chase scene entered in media res? The armed-escort arrival of dubious capitalists on the trail of some as-yet-underexploited resource? (Is there any more potent symbol of ostensibly removed colonialism’s lingering presence than the unkillable, diesel-fueled Mercedes that still stalk the globe?) As the sun sets and the caravan moves closer, the camera inches from a far-off, locked-down wide lens perspective to closer views moving around the procession, until we finally realize the dune buggies bear cameramen. This is a film shoot, and when the shot is achieved one of the crewmembers pumps his arm in victory.

The first half of Ben Rivers’ new feature observes the production of Oliver Laxe’s second feature, Las Mimosas; the second half adapts the Paul Bowles short story “A Distant Episode,” from which the film derives its sprawlingly ominous title. Laxe’s excellent first feature, You All Are Captains, was a Kiarostami-ish self-reflexive exercise in which Laxe and a group of Moroccan adolescents (his actual students) attempt to collaborate on a film about their classroom life. The kids eventually rebel, and an exasperated Laxe asks them what kind of movie they’d like to make; the considerably more becalmed, hanging-out-by-the-olive-trees second half is their answer. “Their” is to be taken with a degree of skepticism: both parts of the film are Laxe’s, and a perfectly equal collaboration that resolves any unsavory imbalance of power can never be achieved when a Spanish teacher comes to school local kids in a far off former colonial territory. The Sky Trembles mirrors the structure of Captains: the first half has Laxe directing his film with local cast and crew, alt-tabbing between French, English and Arabic as need be, while in the second half he wanders into a nightmare fictional landscape, where he’s kidnapped, tortured and enslaved by the locals. The first part is “his,” the second “theirs” — but, of course, it’s all Rivers.

The making-of portion captures filmmaking as a nomadic desert endeavor, in the kind of production that makes you wonder how in the world insurance was obtained. Perhaps it wasn’t: there’s a heart-stopping moment when an actor flops from a cliff down onto a mattress resting on cardboard boxes as everyone prays they hit his mark. We’re constantly aware that Rivers’ vantage point is decidedly not Laxe’s, both because he’s staying out of the way and because he is unavoidably a different if sympathetically aligned director; presuambly we’ll be seeing the new film next year or thereabouts, and images of the making-of will still be stuck in our heads as we reflexively compare/contrast shot choices. The camera’s presence as an observer isn’t easily forgotten, meaning that the second half isn’t as nasty as it could be: even when things take a turn for the dramatically worse, the patently staged quality takes the sting out, and the nature-induced calm settles like a calming poultice over the harshness.

I can’t improve on Leo Goldsmith’s thorough/essential overview of the film, part of a larger series of interlinked projects (book, short film, installation). Sky Trembles is in keeping with Two Years at Sea and Rivers’ collaboration with his fellow Ben Russell on A Spell to Ward Off the Darkness, with yet more scenes of smoke drifting from a campfire and an emphasis on film grain. In Q&As for Spell, the Bens said they made the film in part to have an excuse to hang out together, and while that’s surely not the whole explanation I see no reason not to take them at their word. Similarly, Sky Trembles — at its core, a take-it-or-leave-it film catering to viewers who like to zone out to landscape portraiture and careful sound design — is another form of filmmaking as travel, latching onto another production in order to pay the desert a visit. This isn’t a spoiler, but a vague synopsis: the film ends with an image of a man running frantically away rather than submitting to watching yet another movie, a feeling anyone who’s spent too much time immersed in the theater knows quite well. Cinema is the goal, the enabler and the albatross around your neck; being a professional peripatetic is nice work if you can get it, and if you can hack the cost.