Back to selection

Back to selection

True Crit

Weekly film reviews. by Howard Feinstein

On the Down Low: Ulrich Seidl’s In the Basement

In the Basement

In the Basement “Fassbinder died, so God gave us Ulrich Seidl,” wrote John Waters in Artforum in 2012. You can find obvious parallels between the directors; both are German-speaking iconoclasts (Seidl is Austrian; Rainer Werner Fassbinder, who died in 1982, was from Bavaria), whose precisely arranged and shot films cloak worlds of odd and over-the-top individuals with a patina of intense, self-conscious color, supplemented with frequently incongruous, unanticipated music.

Before it became de rigueur, they explored in depth the intersection of the personal and the political in unique, ideologically loaded and often grotesque narratives. It’s not by chance that their bodies of work foreground the relationships between sadists and masochists, aggressors and victims. The films dramatize the role of power. The character-versus-character model (love, friendship, office politics) is by extension an indictment of an Everyman’s collision with stronger forces: governments, higher classes, corporate interests, ethnic, religious, and national groups, or, more generally, a greater, difficult-to-label social fabric ridden with perplexing inconsistencies.

“Wherever people are allowed the possibility of exercising power over others, you find oppression, humiliation, exploitation, and abuse,” Seidl told the Austrian critic Markus Keuschnigg. Fassbinder and Seidl were always above ground in their examinations of social glitches, but in In The Basement, the latter has gone under, puncturing a private domain — the cellar, a big deal in his homeland — in large part to access carefully disguised discrepancies in the power matrix. (Co-screenwriter is his wife, Veronika Franz.)

Power is based on fear; the notion of hierarchy rests on it. At the beginning of In the Basement, a nearly catatonic man sits waiting next to a glass aquarium containing a tiny, frightened guinea pig and a thick, long snake that leers at its upcoming meal. As predictable as it is, the rapid-fire climax jolts the viewer out of passive mode. Completing the bracketing is one of the final scenes, which features a thick-torsoed, skimpily clad prostitute locked in a cage, attempting to free herself from captivity. It’s insignificant whether this depiction is documentary in the conventional sense or fully simulated — what Seidl terms staged reality. He constructs a special brand of hybrid. He tells Keuschnigg:

I want to discover my own view of the reality I find. Your perspective of reality is the cinematographic gaze that shapes that reality. Through it I try to show what I see, what I’m touched by, what I want to reveal to my viewers.

He is a combo of cinematic architect and interior designer. His aesthetic guided by a somewhat cold symmetrical bent and crisp mise-en-scene, with the aid of new DP Martin Gschlacht (known for his work with Jessica Hausner), he accentuates the sense of confinement, the claustrophobia in these dungeons: holding on the low ceilings, ubiquitous pipes, utilitarian stairways, laundry machines, and storage compartments, which are as visible as kitsch ornaments (Nazi paraphernalia, cheap porcelain figurines and beer mugs), wall decorations (trophy exotic animal heads), underwhelming sofas and chairs (really bad plaids), and fold-up card tables that fail to add cheer. Whether the accoutrements are tasteless or just boringly plain, the overriding minimalism enables a near-constant focus on sating the psychological impulses and drives that are the spaces’ raison d’etre.

He reveals intimate obsessions that generally fizzle out above those tiny windows barely above ground level, just below the ground floor, which block most light, a tease that is as unwelcome as the sun is for vampires. (Seidl claims that his idea for the project preceded the uncovering of two notorious home-imprisonment cases in his native Vienna: Wolfgang Priklopil in 2006 and Josef Fritzl in 2008. Could there be something unsavory in the schnitzel?)

The character studies and observations would not be evident in other domestic settings, such as the living room, the bedroom, the patio. The film is like a plunge into the unconscious, site of our dreams and nightmares, where private, often dark thoughts are unconfined, actions given free rein. He is privy to secret monologues, like the ones spoken by Catholics one-on-one to a statue of Christ in Jesus, You Know (2003). He spies, as he did on owners with excessive physical feelings for their pets in Animal Love (1995).

In a more public milieu, a bar, he eavesdrops on nationalist racists in one of his segments in the omnibus film State of the Nation (2002). But it’s not all uncomfortable for the viewer: He adds humor, perhaps for the same levity Hillary Clinton called for during her inquisition by the Republican poseurs on the Benghazi investigating committee.

Seidl says he feels affection toward his subjects. In In the Basement you can’t help but wonder why his subjects are so…unattractive, if the truth be told, at times right out of the Diane Arbus playbook (no August Sander here). But you sense a loving attraction when you trace his career back to the marginals and eccentrics to whom he has always given screen time: migrants, the misshapen, senile geriatrics, unashamed sublimators of love, outrageous denizens of tacky suburbia, even rightwing xenophobes, especially at the time of the notorious hatemonger, Jörg Haider.

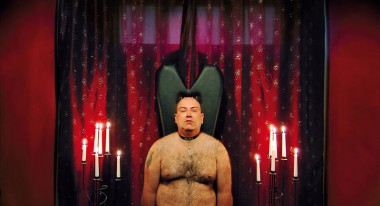

In two different scenes in the new film, he almost identically honors masochists: a formerly abused housewife and a hairy-backed male slave, placing them mid-frame with a series of electrical bulbs or candles on either side. It does not matter that we have seen the man lick clean both a bathtub and his wife’s vagina, and do the dishes, with weights dangling from his balls, or that the woman has presented her ass to the camera while a client whips it until it turns red. He poses them as royalty. Satisfying their libidinous inclinations is just as noble a pursuit as the goal-oriented tasks lauded upstairs. The movie makes the premise of Upstairs, Downstairs seem more than dated: It’s facile.

The film returns again and again to the same characters, with a few one-off exceptions: an elderly man watching his electric train, another surrounded by electronic gear — punctuation. (A recurring tableau of immobile, forward-facing women next to a putrid yellow washer and lime green dryer occupies the middle ground. Their posturing literalizes a comment made by the heavy prostitute that she left her sales job because she didn’t care to be treated like a machine.)

The most tender participant repeats on camera a version of a story she has previously told her director. The bubbie walks down to her storage closet where she trades off lifelike “Reborn” baby dolls to cuddle and talk to. Seidl says that everything in his films is choreographed, that he regularly uses fiction-film strategies.

The circusmaster here is the mischievously named Fritz Lang, a very bad tenor proud of his high-C, who belts out opera standards in his large vaulted basement. There he runs a shooting gallery, teaching classes to other seniors and doing a lot of target practice himself. His gun fantasy is as delusional as his self-image as a talented singer, but as usual, Seidl films without judgment—and without alternatives. The laying out of contradictions without solutions is the classic anarchist position. He once explained:

I try to cast an unflinching gaze on life. All my films are the product of my humanistic world view — even if they do disturb, provoke, or shock… [They] are critical not of individual people but of society, [but] I don’t possess an ideology for improving the world.

We return often to the downstairs den of Josef Ochs, more gregarious than the others, who hosts alcohol-fueled chat sessions with fellow fans of Nazi relics. Ochs takes his commitment seriously: He spends a lot of time brushing Der Führer’s portrait (his “favorite wedding gift”), dusting the uniforms of store mannequins fully decked out in Nazi regalia, and mopping the floor in preparation for his visitors. (From the male love slave to Ochs on, most of the characters, especially the men, engage in housecleaning. Everything is sauber — clean — no matter the context. Hygiene and subjects that society deems dirty are not mutually exclusive. Remember, this is a culture in which mini-wastebaskets rest on table tops so that garbage does not accumulate. And don’t forget the washer and dryer.) Ochs is so cut off from any other world after work that once he pulls into his underground garage full of reproductions of art about Austrian history, the closest we get to his wife is the dinner tray she sends down to him.

It is not easy to keep in motion a narrative comprised primarily of shots that are held much longer than necessary and that are lean on camera movement. Seidl manages to create a propelling tension between subject matter and structure. Symmetry, often two-shots, diminishes the uniqueness of each character. On the other hand, everyone in the film freely actualizes his or her own individuality. This set-up is not easily resolved, nor need it be. It is a clever ploy to extract the dynamic from the static. You could say he brings to life those otherwise marked for their particular forms of solitude. Ein Prosit to the basement. Better yet, bottoms up!