Back to selection

Back to selection

Five Boats on the River: Ciro Guerra on Embrace of the Serpent

Embrace of the Serpent

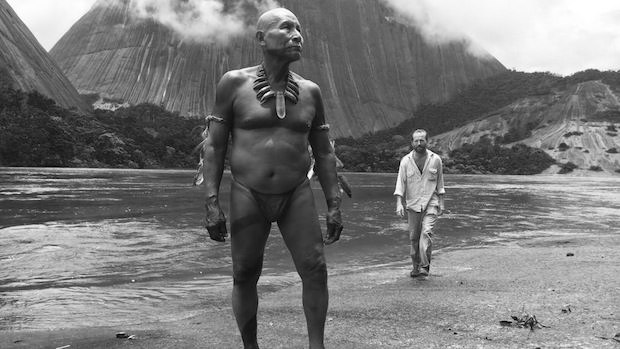

Embrace of the Serpent Ciro Guerra’s third feature Embrace of the Serpent is bracing for the novelty of its setting alone: a feature hasn’t been made in the Colombian Amazon region for 30something years. Without leaning solely on novelty value or simplistic exoticism, Embrace tells two stories. One, set in the early 20th century, is of Theodor Koch-Grunberg (Bivjoet), a real German ethnologist/explorer; at the story’s outset, he’s gravely ill and needs the help of solitary warrior Karamakate (Nilbio Torres) to find a rare plant that can cure him. Another story, some 40 or 50 years later, finds older Karamakate (Antonio Bolívar) guiding Richard Evans Schultes (Brionne Davis), another German who claims to be in search of the same plant because he’s never been able to dream.

The Amazon looks dazzling in black and white, with considerable time spent on hypnotic shots of river travel from the boat’s prow. Economic exploitation as manifested in the ugly conditions on rubber plantations is a recurring motif, climaxing in an Apocalypse Now-ish visit to a nightmarish mission combining, as the older Karamakate observes, “the worst of both worlds,” with ritual hallucinogens consumed by natives in thrall to a Western missionary who’s convinced the Indians he’s the Messiah. A climactic caapi (a plant-based hallucinogen) trip is the film’s sole rupture into color. Over the phone, Guerra discussed his unusual and complicated production.

Filmmaker: You did research for four years. What was this process like in terms of travel?

Guerra: I spent about two and a half years going back and forth around the Colombian Amazon, which is a very big place — about the size of France. The first year I was doing more theoretical research in libraries, reading books and articles. I had an anthropologist friend who knows a lot of people in the Amazon and has worked with them in several places. We’d go with him and stay at the houses of elders, shamans, families and people who were close to him. We spent a lot of time talking and watching the places.

It was also location scouting. I was looking, in the first place, to see if we could do the movie there. We needed places that were reachable by air, in which the rivers had banks, because a lot of the movie takes place in banks. We also needed rocks and rapids. In the Amazon, there are so many different kinds of rivers — rivers that are white, red, black, green, brown. The Amazon is not just one thing, there are so many different shades to different places. Also, the heat and the mosquitoes — there are places in which the mosquitoes can be really insufferable, in which there are very little fauna. So, a lot of different considerations, all of which add up to what feels right.

Filmmaker: How big was the crew you had with you on a regular basis? Did you have a regular base that you returned to?

Guerra: The crew was about 40 people. The place we found was in the region of Vapues, at the border of Colombia and Brazil, two and a half hours away from the nearest city that we could arrive at by plane. You went two and a half hours on a road that was in very bad shape, and arrived at a camp that was built in order to build a hydroelectric power plant. It’s a camp where people can stay — not a hotel at all, not very comfortable, but it’s OK. This camp is right in the heart of the jungle, so that was our main base. From there, we would take boats or walk around. In half an hour we’d be at the locations. We started from the camp every day. That lasted about four weeks. Then we did two weeks in the city — not a city, it’s a village, but it has electrical light, so that’s where we did the mission and night sequences. From there, we took a plane and did another week in the mountains for the scene at the end of the film.

Filmmaker: Can you tell me a little about the practical aspects of shooting on the river? It looked really difficult to do.

Guerra: Yes. We must have spent about two weeks on the water. For me, the most difficult scenes to shoot were the quiet scenes on the boat in the middle of the river, because the river is constantly moving. We had a boat for the actors, but we also had a boat for the camera, a boat for the sound, a boat for the wardrobe and makeup, and a boat for production. So putting five boats together for a shot, we only had one minute before they would drift away. Those scenes that are very quiet and don’t seem so complicated were the most complex, because you need to synchronize all this with the stream of the river and the actors.

Filmmaker: So you were also recording location sound on the water?

Guerra: Yes. A lot of the sound that you hear was recorded on location. Every once in a while, a motorboat would come along going to the villages, and it would be a problem because you could hear the sound from a while away. So the sound would come, and it would really take a while. But in these areas, there’s very few boats that go there.

Filmmaker: I’m guessing your actors had to learn the native languages, at least phonetically?

Guerra: Both Jan and Brionne, the Belgian actor and the American actor, took a huge chance: come to Colombia, come shoot the film in the jungle, do it in indigenous languages. We sent them how to say phonetically every word, every phrase, and what they meant. They took months to prepare. When they arrived in the location, they would speak and the indigenous people would understand perfectly. It’s the kind of rigor that you can find in theater actors — they do their homework with a lot of commitment and passion.

Filmmaker: How do you direct if you don’t understand what’s being said? Do you trust your judgment or do you check with one of the indigenous actors?

Guerra: With the Amazonian actors, I could speak in Spanish. It’s not their first language, but they all understand and speak it. For me, it was a very interesting experience, because since you don’t understand the dialogue, you’re not thinking about whether the text is right or not. You’re thinking about whether the emotion is right and comes through beyond the words. I think that’s the way you should direct.

Filmmaker: You just won the audience award for best film supported by the Hubert Bals Fund at Rotterdam. There’s a lot of argument about whether the fund tends to favor the creation of certain types of film languages, and how that influences the cinema of the countries they’re supporting. Do you have any opinion about that?

Guerra: For us, the Hubert Bals Fund has been a big support. They came in at a stage of development where it was really hard to find financing for the film. They give you complete artistic and creative freedom. I am aware that in the past ten years or so, there were quite a few films that had a similar aesthetic, a similar use of language, that became a sort of staple of the Hubert Bals Fund. But I think if you look into all the films they have produced in a more rigorous way, you will find a lot of diversity.

Filmmaker: Can you tell me about filming the sequence at the missionary camp? There’s a lot of chaos, with a big crowd of people running around.

Guerra: It’s a moment that had to be different from the rest of the film, in which they catch a glimpse of a sort of dystopia. The story takes place in such a concentrated setting, there are very minutes in which the film really takes a look at the outside world. This was one of those moments, and it was very important for me, because it was the moment in which the characters have a vision of what the world is when there’s no dialogue between the cultures, there’s just violence — cultures stacked on top of each other in a violent way. So the sequence had to be a moment that was out of control.

We had a coach who prepared the extras to act in a particular way. All the extras you see in the film are really indigenous people, so this is their first experience [acting]. For them, it was fun, like a game. So they would be doing these very crazy things, but the way that we staged it was more of a funny thing for them. What marks the tone is the way we lit it, and the way the camera moves in that sequence. We used smoke to create an atmosphere that was a nightmare. We drew inspiration from paintings, mostly Goya and El Greco, to create this atmosphere of a horror. We used more the tools of cinema than the tools of acting. We directed the performers as moving space, rather than them acting.

Filmmaker: Can you also tell me about the caapi drug trip at the end?

Guerra: What you see is the imagery of the Barasana people of the Amazon. That’s the way they represent the spiritual world, which is something you cannot see, something you can only glimpse for a very brief moment. That sequence is essentially a cinematographic representation of the different stages of the journey that they describe. We didn’t want to turn it into a special effects show; we wanted it to be very primitive, something like what a child could draw. For them, the spiritual journey is going back to those things that you could see as a child, and the way you could understand things as a child that you lose as you grow up. Also, when they describe the spiritual journey, one thing that is very clear is that the world fractures itself. A crack is open in the world, and you can glimpse for a moment the spiritual world. So the film needed to fracture itself at this moment in order to represent that — to fracture itself and become something it had never been before. And it needed to be in clear opposition to everything that had come before.

Filmmaker: You mentioned in another interview that yours was the first film to shoot in the area in 30 years. What was the last film to shoot there before you?

Guerra: It was probably Kapax del Amazonas, which is sort of a version of Tarzan. Even earlier, there was Amazon for Two Adventurers [released here as Two Sane Nuts], which I think was an Italian-Columbian co-production, also a B-movie type of thing.

Filmmaker: These same like the kinds of films that, in their representations of the Amazon, are what your film stands against. Did you look at them before starting production?

Guerra: These are films that are not so easy to find. We knew them as references and we’ve seen fragments of them, but we weren’t standing against them. It was just another time and another way of filming. The thing is, during the following years the armed conflict became very intensified in Colombia. Some of the regions of the Amazon were taken over by FARC, so a lot of people were afraid to go there. It was really not possible, for security reasons, to bring a production to the Amazon for a very long time.

Filmmaker: The press kit says that Antonio Bolívar had been in a film production before but prefers not to discuss it because he felt it was a disrespectful portrayal of the indigenous population. Were there trust issue you had to overcome when approaching your native actors?

Guerra: Antonio had been in a short film about 25 years ago that was made as part of a program by the Ministry of Culture. He had a really bad experience; he was cheated, he was treated very badly, and he was deceived, so he said he would never do it again. We explained to him what we wanted to do, and he connected very much with the story. He found it was important, so he looked at us and said, “I think I can trust you.” So it wasn’t that difficult to convince him, but it did take some convincing.

Filmmaker: In preparing for the film’s release in Colombia, did you have any goals insofar as raising public awareness of the Amazon? How do you feel the film has been received?

Guerra: In Colombia, it was released on the independent circuit, because the theater owners didn’t think that theatergoers would go see an Amazonian film in black and white. It got a very small release, but it did very well in that small release. It’s been playing for nine months now. After the film became an Oscar nominee, then it got a wide release in all the theaters. The numbers have been tremendous.

The interesting thing about the first release is that it sparked a lot of debate. On one side, there was political debate, and there was also scientific debate in the anthropological community, and there was also, of course, cinematographic debate about representation and the film in and of itself. Some anthropologists didn’t see the film as a work of fiction, so they insisted on pointing out the things that were not accurate. But the film is clearly a work of fiction, so there was a debate on to what extent you can fictionalize certain things. There was also a debate on how true the representation of the Amazon is, and a debate on where the film stands politically. It was well received by people on several sides of the political stage, so some people needed the film to make its political stance more clearly. Left-wing people wanted the film to be more clearly left- or right-wing. It’s a strange thing, when people want the film to have such clear politics. But I’m not interested in that; I’m interested in the grey zones and contradictions of this political debate, rather than making political statements.