Back to selection

Back to selection

Shutter Angles

Conversations with DPs, directors and below-the-line crew by Matt Mulcahey

How They Pulled Off Creed’s Two Biggest Shots: A-Camera Operator Ben Semanoff

There are few moments in cinema as iconic as Rocky Balboa bounding up the steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, with Steadicam inventor Garrett Brown galloping alongside him off-screen.

The technology for Brown’s camera stabilization system was new enough at the time that the seminal shot required a crew member to sprint behind Brown with two car batteries attached to the camera via jumper cables in order for the rig to function in the cold Philly winter.

Creed, an expansion of the Rocky universe from Fruitvale Station director Ryan Coogler, offers a barometer for the Steadicam’s evolution with its dazzling array of extended, balletic, and intricate camera moves — including an entire boxing match that unfolds in a single, unbroken 4 ½ minute take.

Creed’s A-camera operator — and Philadelphia native — Ben Semanoff details how the filmmakers pulled off the movie’s technical wizardry and how his Steadicam education began with Garrett Brown himself.

Filmmaker: When I interviewed the legendary Steadicam operator Larry McConkey, he talked about the early days of training with Garrett Brown in Philadelphia. They worked in Garrett’s house and the only rule was that they couldn’t scrape any paint or break any of Garrett’s wife’s things. I’m guessing by the time you trained with Garrett the workshop was a bit different.

Semanoff: I’m sure it was much more sophisticated than what Larry experienced back then. They had a facility that they rented for the workshop so there was no concern about scratching walls or damaging any vases or any of Ellen’s stuff. (laughs)

Filmmaker: What drew you to your first Steadicam workshop with Garrett?

Semanoff: The Steadicam always had this allure for me. I had just started a small company in Philly and I had bought a Steadicam and as soon as I got it I realized it was way more complex than I had anticipated. (laughs) So I quickly signed up for a workshop and it just so happened that the head instructor, this operator named Jerry Holway, wasn’t available. He was off doing a movie. So Garrett ended up being the head instructor and for whatever reason he and I hit it off and sort of started a friendship. We actually went on to become business partners in one of his cable camera systems.

Filmmaker: Had you even had a Steadicam rig on before you bought that first one?

Semanoff: I’d never had one on. (laughs) It wasn’t a huge investment. It was a lower-end, older video-based system. I think I found it on eBay for like $6,000. At the time I was buying equipment for my business and it fit into the capital we had available to us. So yeah, I went for it.

Filmmaker: How long did it take before you felt like you knew what you were doing?

Semanoff: It probably took about a year before I really felt confident enough to take on jobs outside of [shoots for] my business. If I used it for one of my jobs as my own boss, I’d go out with it and I was the only person I had to answer to. But to take on a larger, higher-profile job and be able to deliver, it probably took about a year. But beyond that, to be able to go in and play with the big boys, that was several years.

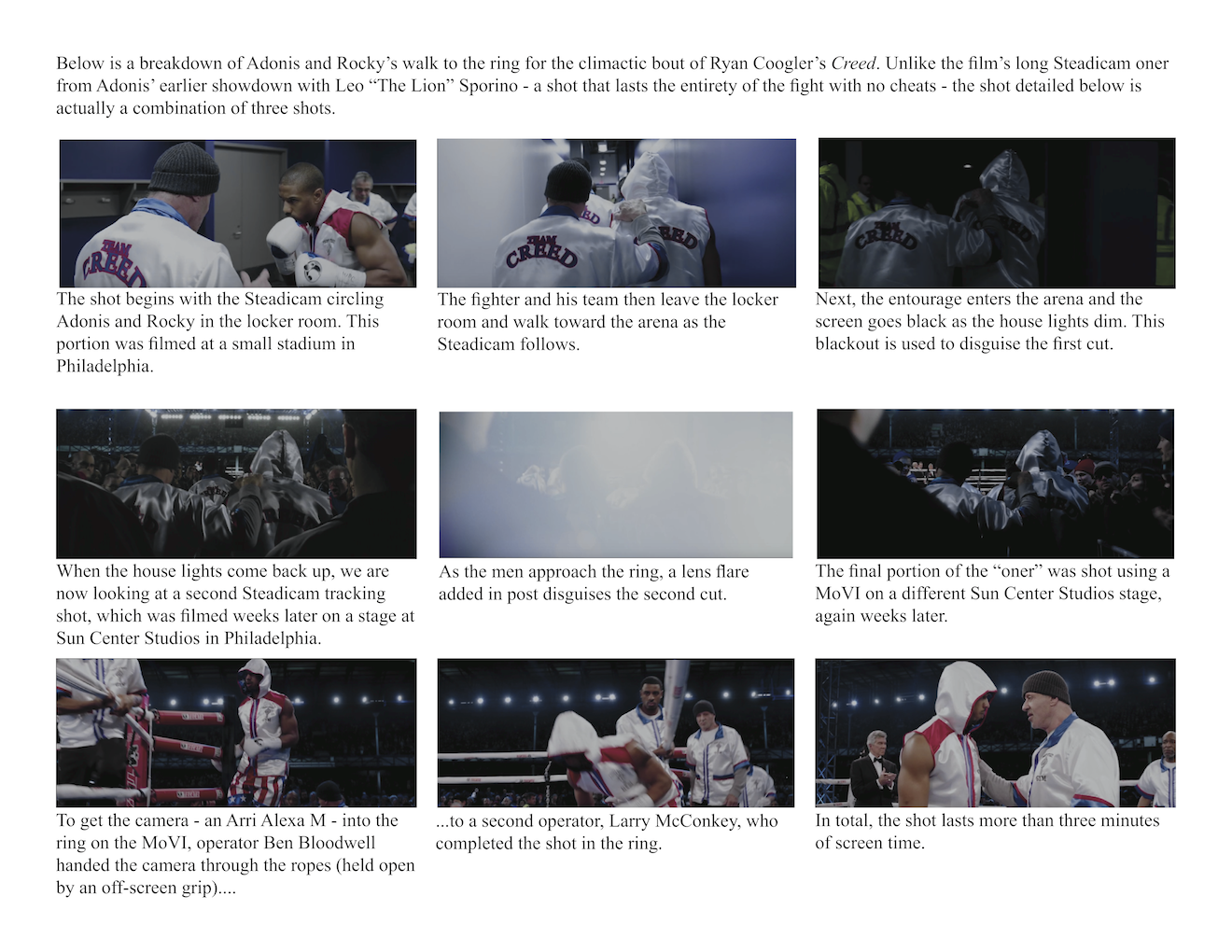

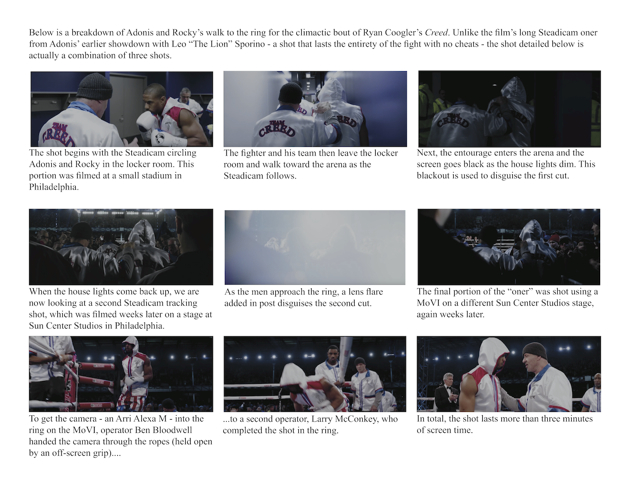

Filmmaker: We’re going to be breaking down two specific shots from Creed — both presented as extended “oners.” Let’s start with the long tracking shot that leads into the film’s climactic final bout. The Steadicam shot starts in the dressing room as Adonis (Michael B. Jordan) warms up and then we track Adonis, Rocky, and their crew through the hallway guts of the arena all the way down to the ring itself. The camera then actually passes through the ropes and follows Adonis into the ring. [Click on the diagram below to enlarge.]

There is a moment when Adonis’ entourage first enters the arena when the screen goes black as if the house lights have been dimmed. Is that a disguised cut?

Semanoff: There’s actually two cuts in there. As we come out of that darkness there’s a cut point to another Steadicam shot that continues as they walk through the first section of bleachers in the stadium. Then there’s a lens flare that they added in post and at that point it cuts to a MoVI shot and the MoVI was used from there to follow him through the ropes into the ring.

Filmmaker: How early in production did that shot start to take shape?

Semanoff: This is actually one of two or three shots that evolved into oners [on the day]. The plan originally was just to follow Adonis and Rocky through the hallway and out into the ring. And then on the day Ryan [Coogler] said, “See what you can do here in the dressing room.” And that became, “Why don’t we just follow them out [of the dressing room] into the hall.” We tried a take and everyone was blown away by how seamlessly it worked.

Filmmaker: The three shots that are stitched together for that “oner” obviously occur in sequence in the film, but how far apart on the schedule did they actually fall?

Semanoff: They were way apart. The locker room was shot at a small stadium — I believe it’s a soccer stadium — in Philadelphia and then the point where they go into the darkness and then they come out of the darkness in the stadium, that was all shot on stage at Sun Center Studios in Philly. The [final piece] after the lens flare was shot on a separate stage [at Sun Center] probably a week later. [Each piece] was separated by at least a week.

Filmmaker: Did you have much experience with the MoVI beforehand?

Semanoff: At that point I’d only had a little experience with the MoVI, but I was familiar enough with the technology to know that single operator mode wasn’t what we wanted to use. In order to pan the MoVI [in single operator mode)], you have to set a threshold in the software that says, “Anything up to this amount of variation, don’t pan, keep it stable. Once I break this threshold — whether it’s a degree or two degrees — that means I’m panning, so please pan.” There’s always a little bit of a lag when it’s in single operator mode. I told production that whoever they got the MoVI from, I had to be able to operate it remotely and I didn’t want to use a joystick. I wanted to use a set of wheels. I’ve operated off a joystick a million times, but a joystick is much better for fast action and that wasn’t really what we were doing. We were following him in a very deliberate way and I wanted it to be a very elegant shot so I wanted the control of a set of wheels. Production searched and searched and searched and they couldn’t find anybody that had that capability and I said, “Well, I know Larry McConkey does because I’ve used his in his shop.” So they got on the phone with Larry and the planets aligned and Larry was available to come in and do a couple MoVI shots and some of the additional camerawork in that big fight scene.

Filmmaker: How many people were needed to pull off the MoVI portion of the shot?

Semanoff: It was actually rather complex. Right now the Arri Alexa Mini is out, which is the perfect compliment to the Alexa for the MoVI, but at the time all that we had access to for that shot was the Alexa M and the M requires the use of a backpack (to carry batteries and an external recorder). So that makes everything much more cumbersome.

So we had operator #1, Ben Bloodwell, and he carried the MoVI behind Michael [B. Jordan] up until the ropes, while a grip carried the backpack (with the batteries and recorder). Then there was a grip in the ring to grab the backpack and another grip holding the ropes open so Larry McConkey could reach his arms through the ropes and grab the MoVI. Then you had me hidden way in the back with the cinematographer [Maryse Alberti] and [Ryan Coogler], operating off of a set of wheels. And then my focus puller was somewhere entirely separate from us.

Filmmaker: Was there a boom op following alongside the camera?

Semanoff: Oh yeah, there was a boom op too.

Filmmaker: Let’s move on to the single-take boxing match between Adonis and Leo ‘The Lion” Sporino (played by Gabe Rosado), which is the first time we see Adonis fight after he’s begun training with Rocky. In contrast to the previous shot we talked about, this was a set piece that was developed in preproduction.

Semanoff: When I first got the job I went in and I met with Ryan and Maryse and they told me they had this idea for shooting a fight in a oner. I thought it was the greatest idea ever. There was a ring that was built in a warehouse that was part of the complex that the production office was in and Michael, Gabe Rosado, and Tony Bellew (who plays Adonis’s opponent in the film’s final bout) had already been training there for weeks and weeks. I came in and started working with stunt coordinator Clayton Barber, and he started showing me the fight — not even with the actors but with stunt guys that knew the blocking. At that point Ryan had just given me a general overview of what he was trying to achieve. He wasn’t even sure if he wanted the shot to be handheld or Steadicam. It was interesting because different people had different ideas based on their own personal perspective. For instance, Maryse always wanted to be very low to feel the lights and the stadium above. Ryan wanted to have a lot of dynamic between the sizes [of the frames] so that we would have moments that we were tight and moments that we were wide. But there wasn’t really a very specific game plan at that point.

Filmmaker: How did the shot evolve during rehearsal?

Semanoff: We started with iPhones on Day 1 [of rehearsing], just using the stunt guys, and I also had to memorize the fight, which was a little bit of a challenge. Then the next morning I sat down with Maryse, Ryan, and Clayton and we watched the videos off of the iPhone and made notes about what we liked and what we didn’t. By day three, we had it roughed out enough where we could then start working with the actors. Once we had them on the same page and Ryan and Maryse signed off on the shot, then we started incorporating the Steadicam a little bit. I was really nervous about the actors colliding with the camera so I foamed out a bunch of the camera so that if they went to throw a punch and as they drew back they elbowed the camera, they wouldn’t get cut.

Filmmaker: Even with a week of rehearsal under your belt, how smoothly did everything go on the day?

Semanoff: I think the most interesting part of it was that we had been rehearsing in a dead silent warehouse, but then when we were about to do take one [on the day] we had 500 background [extras] in the stands. What neither myself nor Michael or Gabe was expecting was that when the 1st AD said, “Alright, let’s go crowd. Start screaming and cheering,” all of a sudden we now have to do what we’ve been doing in dead silence with a screaming crowd. And I remember looking at Michael and Gabe and all of our faces went white. But then we did a few takes and we started getting into it. We started to feel the energy of the audience. Somewhere around take seven, sound requested a silent take for their purposes and we got maybe a minute into that take and we just stopped. Michael, Gabe, and I just looked at each other and we knew that we couldn’t do it without the audience. That crowd really fuels your adrenaline like nothing you can believe.

Filmmaker: Can you put into perspective how physically taxing a shot like that is?

Semanoff: Well, I also like a heavy Steadicam because a heavy Steadicam means it’s more stable. So I’m always riding that line of putting more accessories on the Steadicam to add weight. It was definitely an exhausting day. We did 13 takes and we probably had 10, maybe 15 minutes between each take to review the take at video village, to talk about things both technical and performance wise, and then we would go again. But, yeah, I went through a lot of towels that day.

Filmmaker: Do you remember what lens millimeter you used?

Semanoff: I’m pretty positive we used a 27mm on that. I wanted the ability to get as wide as possible and any other lens that we tried didn’t really allow for that head-to-toe, big wide moment in the scene.

Filmmaker: Can you talk a little bit about the job your focus puller did on that shot. The whole thing looks sharp as a tack.

Semanoff: My AC Brett Walters is amazing. There’s not a second of that shot that is soft. If you can believe this, he wasn’t even in a position where he could see the actual actors. He was hidden somewhere in the back behind a bunch of floppies and he was pulling focus straight off the monitor and he nailed it. I’m on a movie with him right now and people will say, “Oh, we’re going to change this or that in the blocking. Do you want to let Brett know?” And I’ll say, “No, he doesn’t want to know.” He feels like it keeps him on his toes because inevitably nothing ever is repeated perfectly. Something always changes — an actor misses their mark, I miss my mark, or an actor ad libs something. If he’s expecting that change, he feels like then he’s not on his toes. He’s phenomenal.

Filmmaker: What was the most difficult section of that shot? Nailing all those whip pans toward the end of the scene seems like it would be pretty tough.

Semanoff: You nailed it. That was probably the hardest part. [When that portion of the scene arrives] you’ve been in the rig for nearly four minutes and you’re exhausted and you’re sweating and now you’ve got your first whip pan to do and you know in your head that if you screw it up, the shot is done. And beyond that, you’re worried that even if you don’t screw it up, you might not get it perfect and then that might be the take they use. There’s a moment where Michael and Gabe are going at it and we whip over to Rocky, who’s slapping the mat yelling, “Now! Now!” and that was the moment where in my head I would tell myself to take some nice slow breaths and get yourself ready. So we whip to Rocky, whip back to Gabe, and at that point, once I had those two whip pans done, I know I had the shot.

Matt Mulcahey writes about film on his blog Deep Fried Movies.