Back to selection

Back to selection

Tribeca 2016: Five Questions for Obit Director Vanessa Gould

Obit

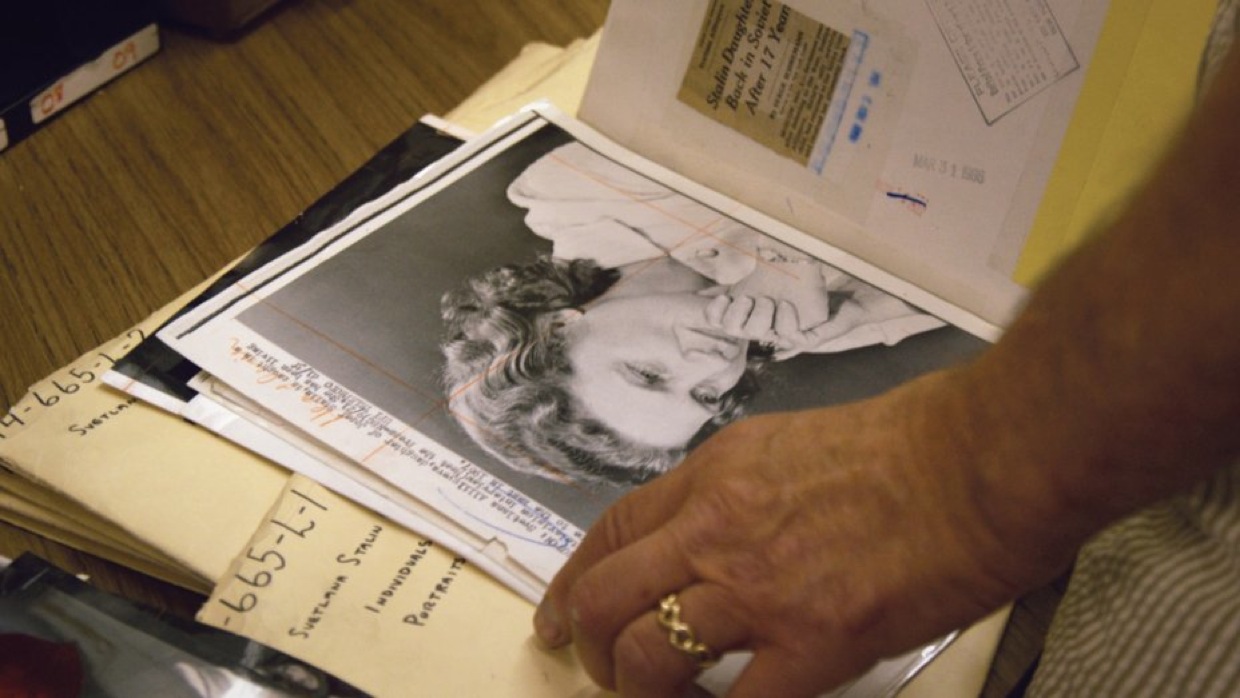

Obit While there have been several documentaries exploring the inner-workings of the Gray Lady, the life and challenges of a New York Times obituary writer is a profession that has yet to receive its due. Working on strict deadlines that arrive at a moment’s notice (such is life and, in effect, death), these obit writers have to be on call to craft a minimal but effective summation of character while working with limited time and limitless resources. A fascinating subject that immediately evokes a plethora of questions (what’s the criteria for determining who gets a Times obituary? How quick is a writer’s turnaround?), it took a common link for director Vanessa Gould to explore the obituary department of the newspaper.

Filmmaker: I’ve read that a character in your first documentary, Between the Folds, influenced the creation of your second, Obit. Could you speak a little bit about that?

Gould: It was actually his death at the height of his artistic career that lead to Obit. He was a shy, somewhat reclusive paper artist living outside Paris. I sent his bio to some major newspapers upon his death, and the only paper that got back to me was The New York Times. They ran a beautiful obituary on him, with a full slideshow. I couldn’t believe that this leading media outlet would commit space on their page to an unknown French artist. It was after that that I began thinking a lot about obits — why they make the choices they make and what purpose they serve — journalistically, historically, and even in a cultural anthropology sort of way.

Filmmaker: How much time you spend with your subjects and how did you identify the “key players” in your narrative?

Gould: We had to be pretty efficient, since Obit writers work under tough time pressures and on deadline, without much time for any distraction. Once they all agreed to participate, we corresponded a bit, and then I did one lengthy interview with each of them at their private homes, each lasting about four hours. We then spent about four to five days shooting in the newsroom. It was pretty lean. We got a good sense of each other that way and what functions we were each serving. For the other subjects in the film — the obit subjects — those were chosen out of many, many stories the writers shared. I was specifically interested in the stories the writers remembered writing.

Filmmaker: There have been several films about the hallowed halls of The New York Times before (Page One: Inside the New York Times and Wordplay come to mind) but never one about this particular topic. How did you find the task of crafting a cinematic representation of writers and the writing process?

Gould: This is one of the things we were thinking about from the very start. We studied the building, the way time of day correlates to the natural lighting and the timing of deadlines. We wanted to convey the sense of the clock ticking, the city buzzing down on the street below. Kristin Bye, the film’s editor, did a masterful job of communicating the passage of time and the pressure of deadlines through clues in the light and sound of the building and the surroundings.

In choosing to film the lengthier interviews with each writer and the desk’s editor at home (versus in the newsroom), I felt from the beginning that the writers should be portrayed as individuals before being portrayed as employees of the Times. By filming in each of their home environments you can see who these people are by the clues that surround them. A “picture is worth a thousand words” type thing…

Filmmaker: In an interview on The Leonard Lopate Show, you talked about the challenges the writers face determining which lives are worth the “print space to commit this person to the record.” Could you speak a little more about that editorial challenge?

Gould: I’m always a little uncomfortable answering this question, and the desk editor Bill McDonald speaks to it best. I think above and beyond they’re looking for people who have done something unique, something no one else did, whether it was an invention, a book, a scientific discovery, a pivotal role in a historical event, etc., by recording these lives in an obituary. It helps to keep the things that have influenced our lives and our culture from falling too far out of sight.

Filmmaker: What camera did you choose to shoot with and why?

Gould: We shot with two RED cameras, and used an Eye-Direct, which is an Interrotron- type mechanism. We knew we wanted a composed, framed look to the each of the interviews, as a way of really presenting them like moving portraits and character pieces. We did very little handheld in the newsroom, and much more was shot in slow moves on sticks to stay in keeping with the formal, composed shooting style.