Back to selection

Back to selection

Shutter Angles

Conversations with DPs, directors and below-the-line crew by Matt Mulcahey

One Perfect Place to Put the Camera: DP Adam Stone on Midnight Special

Jeff Nichols on the set of Midnight Special

Jeff Nichols on the set of Midnight Special In the summer of 2005, with roughly $50,000 scraped together from friends and family, Jeff Nichols made his directorial debut Shotgun Stories not far from where he grew up in Little Rock, Arkansas. Two things haven’t changed since – Michael Shannon has been in front of the camera for every Nichols movie and cinematographer Adam Stone has been behind it. That includes Take Shelter, Mud, and now Midnight Special, which elevates Nichols to the studio realm with a tale of a father (Shannon) and his “special” son (Jaeden Lieberher) on the run from the government and a religious cult with a potentially apocalyptic event looming.

Stone spoke to Filmmaker about this latest collaboration, which is now out on home viewing platforms.

Filmmaker: I read a stat that the budget for Midnight Special was double the combined cost of your previous three films with Jeff Nichols. In what ways does that additional money change the way you work and what part of your approach stays the same regardless of budget?

Stone: I really wish Midnight Special was double the budget of our three previous films combined. If that was the case I would have asked for more shoot days. In actuality, Midnight Special’s budget hovered around $18 million. Our producers were very keen on sticking to those numbers because they made a fair amount of concessions with Warner Brothers during the initial stages of negotiations. Believe it or not, we cut a week out of the schedule to accommodate the budget. With that said, the project was extremely demanding. We had very long shoot days in remote locations. As Jeff and the rest of the crew can attest to, the shoot was taxing.

Though we encountered a lot of obstacles Midnight Special was a great learning experience. We got to experiment with pursuit vehicles, helicopters, and constructing elaborate VFX sequences. We also learned to be misers at the same time. We were always acutely aware of the tight schedule and living within our means. Concise shotlists, using costly equipment wisely, and making sure our crew was happy and not pushed too hard were always concerns. So yes, we had more money and more equipment than previous films, but our approach and style did not change. Shooting Midnight Special was like boot camp. It was a huge challenge and it hardened us. It showed we can work within the parameters of the studio system and still shoot a compelling movie.

Filmmaker: Nichols has talked about immersing himself in whatever genre he’s about to tackle. How does that preparation extend to you? Does he share a look book of references or suggest films for you to watch?

Stone: Since Jeff writes his own material he’s immersed in the project for years. He’s so consumed by the project he constantly dreams about it. He will wake up in the middle of the night and work on a single line of dialogue after a dream about a scene. He also has the unique ability to zone out and daydream about the project. He literally checks out for a few minutes while standing in front of you. He’s there, but not there. I’m pretty sure he’s in his own virtual reality, checking in on the script, testing theories, adjusting plots, and developing characters. This sounds a little crazy, but I’d love to do a mind-meld with him to gain his insight.

Since I can’t do a mind-meld, Jeff and I usually trade movies, pictures, and music during preproduction. I also edit together a video with some evocative images and an interesting music bed. People really seem to dig the video. It’s way more fun than sifting through a giant PDF of pictures.

Filmmaker: Nichols has cited the impact of Starman and Clint Eastwood’s A Perfect World on Midnight Special. What did you hope to evoke from those films?

Stone: Starman had particular importance because it served as a springboard for the look and feel of Midnight Special. We loved the simplicity of the directing, lensing, camera movement, and dug its color. It was great to show Starman to our department heads as prototype to Midnight Special.

A Perfect World was viewed because of the story. Ostensibly, A Prefect World and Midnight Special are similar because they’re both road movies about a man (played by Kevin Costner in A Perfect World) and boy on the run. We loved the chemistry between the boy and Costner and definitely wanted Jaeden and Michael Shannon to exhibit a similar dynamic.

Filmmaker: Nichols often talks about there being “one perfect place to put the camera” for any given shot. How do you find that one perfect place? And how is that approach complicated by shooting multiple cameras like you sometimes did on Midnight Special?

Stone: Yes, Jeff is very particular with camera placement, and yes, I agree, there is usually one perfect place to land a camera for the story he wants to tell. The recipe for perfect camera placement on a Nichols movie consists of a couple of things – the first of which is a ton of location scouting. As I mentioned before, Jeff writes all his material, and while writing the script he also constructs the shoot locations in his head. The locations he constructs are as important as the characters. He actually figures out camera set-ups and edits via the locations he envisions. This is an amazing quality and also a pain in the butt for location scouts. On Midnight Special we honestly scouted fifty ranch houses before we found the perfect one (for a scene set at the home of a former cult member named Elden). Once we found the hero ranch house with the correct layout, everything fell into place. In a matter of a day, using a few stand-ins and (the director’s viewfinder app) Artemis, we mapped out all the shooting sequences and camera positions for Elden’s house.

The other element that dictates perfect camera placement in our films is point of view. I know it sounds rather pedantic but we always ask, “Whose point of view is this?” before the camera lands. Good camera placement is our version of shorthand. It’s a concise method of telling the story through the eyes of the characters without a lot of superfluous information. We usually steer clear of extraneous angles and camera movement so the story is told in a very simple/direct manner.

On rare occasions we roll three cameras on dialogue heavy scenes. It helps keep the scene fresh and saves the actors. We rolled in this configuration when Calvin (Sam Shepard) is questioned by the government. This is not optimal for perfect camera placement but we usually find a good home for each one. It’s always fun to see three film cameras with 1000’ mags sandwiched together. It’s equally entertaining to watch us operate them. When shooting in that manner we always shoot (all the cameras) in the same direction so we don’t compromise lighting.

Filmmaker: For Midnight Special you opted for the same pairing of Panavision Millennium XL2 cameras and G Series anamorphics that you used on Mud and again on the upcoming Loving. If ever there were a movie to try out the Alexa on it would seem to be Midnight Special – even a die-hard film guy like Robert Elswit went Alexa for some of the night scenes in Nightcrawler. Did you ever seriously consider not going with 35mm?

Stone: As Jeff and I get older teaching us new tricks becomes harder and harder. We are stubborn old dogs and like to stick to what we know. We love the look of film and there was never a discussion to shoot anything but celluloid. Out of necessity, we did dabble with digital (Arri Alexa XT and M) on nighttime process trailer work, which allowed us to place digital cameras where a film camera and mag would not fit. I’m sure we will shoot more digital in the future as the technology develops and lenses are better designed for the medium.

Filmmaker: Once you settled on shooting film, talk a bit about the decisions that come after that. What are you looking for in a 35mm camera body? Is it more ergonomics? And in terms of film stocks, how much have your options been winnowed down by Kodak really being the only player left?

Stone: Oddly enough the camera body plays a huge role in the look of the celluloid that passes through it. I love Panavision G Series lenses and I can only shoot those lenses on Panavision cameras or cameras that have been Panavised. Without G Series lenses Midnight Special would have a completely different look. As far as ergonomics go, I dig the XL2 because it’s compact and easily configured to handheld or Steadicam mode.

I do miss having more than one company producing film stock. I shot my first movie on Fuji Eterna and really loved the look. Fuji also made a fascinating 500 (ASA) daylight stock that was gorgeous. Though Kodak is the only game in town, and their line of stocks keeps getting smaller, their product is beautiful. I really hope they are around for decades to come.

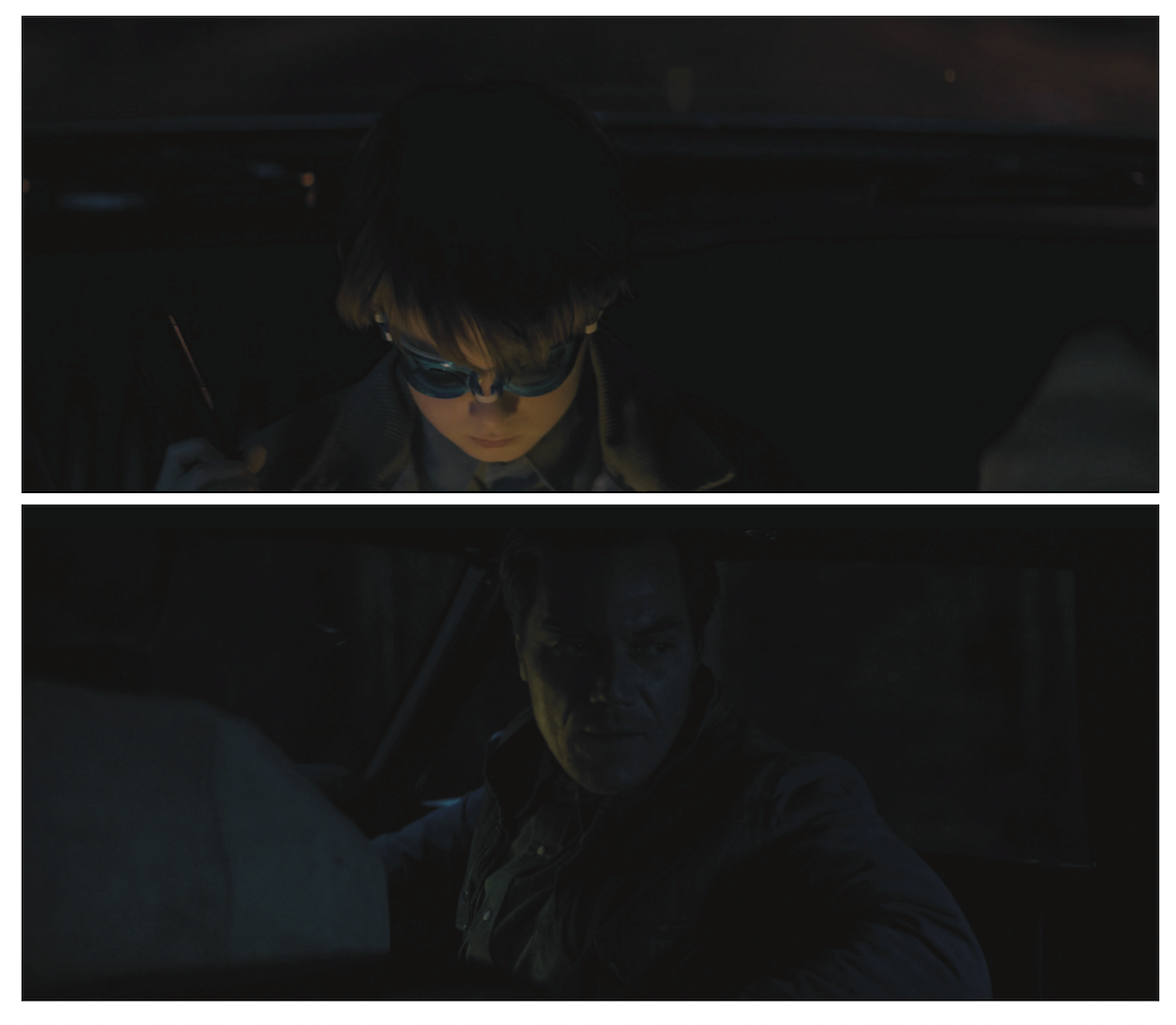

Filmmaker: Let’s break down a few scenes and shots from the film, beginning with the early driving scenes. I was surprised to read an interview with Nichols where he said that the first spark of an idea for Midnight Special was not the theme of parenthood or doing something related to the sci-fi genre. It was really just an image of Michael Shannon driving a cool car at night. Talk about how you approached lighting those early scenes of Shannon, Joel Edgerton (who plays a state trooper aiding the father and son), and Lieberher in that car. I love the color contrast in those shots.

Stone: We wanted the initial scenes to be as authentic as possible so we used a process trailer instead of greenscreen. We always skew towards realistic shooting environments because they really affect how the actors and crew approach a scene. Our basic tenet is “the more the real, the better.” Unfortunately, the more real sometimes equals a giant pain in the butt.

The rig for the process trailer was quite a build. An array of M40s were trussed on top of the car to illuminate the passing environment. Two 1K open-faces were bounced into 4x4s on the deck of the trailer to mimic the glow of the headlights. A Kino Flo was armed over the rear window to backlight Jaden. There were several LEDs pads inside the car to augment the glow of the dash. And the last element was a standard flashlight rewired for higher output. We also crammed two cameras, two operators, and two ACs on the rig. To make things even more exciting it was sleeting that night. The driving sleet combined with a process trailer traveling at 50mph was harrowing and bone-chilling.

Though it was a tough scene to shoot I was happy with the imagery. Using a process trailer really enhanced the authenticity of the scene. The actors had a realistic working environment, the cameras had a “liveliness” to them, and the lighting looked organic, not overlit, because of the confines of the process trailer.

Filmmaker: In this next shot a caravan of vehicles creep over a hill – the beginning of an FBI raid on the religious order’s compound.

Stone: This location was amazing. We shot this in Mountainair, New Mexico. There was a small group of undulating hills that stretched into a beautiful sunset. We shot the scene several times with two cameras until the light was perfect. We used the last and darkest take in the sequence. I love how the headlights and setting sun fall within the same ratios and color space. And the flares from the passing busses were icing on the cake.

Filmmaker: In this scene, Alton (Lieberher) is questioned by an NSA agent played by Adam Driver.

Stone: We actually shot this scene 2.5 times. This was literally the scene that would not go away. The first time was at an Air Force base, the second time was on stage, and the last time consisted of two pick-up shots filmed several months after the show wrapped. Though I like the way the original scene looked, the final scene was better constructed. I love the clever interplay between (Lieberher) and (Driver) on the monitors — the original scene did not employ that element.

Filmmaker: Though Take Shelter included effects work, Midnight Special is a giant leap forward with more than 300 VFX shots. Walk me through one of those shots – this scene in which we see a glimpse of Alton’s powers.

Stone: This is probably my favorite scene of the movie. Jaeden gave an incredible performance and all departments came together to pull off a good VFX sequence.

Jeff and I really wanted the effect to look organic and we made a conscious decision to use interactive lighting and not solely rely on VFX. To look authentic the effect had to interact with Alton and his environment. For example, if Alton put his hands over his eyes the light would wrap around his fingers and glow his hands – same idea as putting your hand over a flashlight. Achieving this digitally was really hard and looked contrived, so we came up with a homespun workaround. The team at Hydraulx built a pair of glasses housing small LEDs. The glasses, though odd looking, provided the interactive light we wanted. After a couple of builds, and help from (LED manufacturer) Cree, we had a great looking pair of low profile glasses with high power LEDs.

After a bit of testing we found the perfect recipe to make Alton’s eyes glow. It turned out to be a weird amalgam of interactive light from the glasses and VFX work. Here’s what we did on set. We shot one take with glasses and repeated the same take without glasses. The take with the glasses provided us with amazing interactive lighting. The take without the glasses supplied Hydraulx a clean plate where they married the interactive lighting with their VFX work. The final images are outstanding. The planning and testing paid off. Each department came together and delivered an organic yet breathtaking visual effect. I’m really proud of everyone’s work.

Matt Mulcahey writes about film on his blog Deep Fried Movies.