Back to selection

Back to selection

Shutter Angles

Conversations with DPs, directors and below-the-line crew by Matt Mulcahey

Darker Shades of Grey: The Night Of DP Igor Martinovic

John Turturro in The Night Of

John Turturro in The Night Of The term “TV coverage” used to be a pejorative, a reference to the mechanical nature of the medium’s visual language. It was shorthand for artlessly cranking out master, two shot, and close-up in order to churn through the high page counts necessary to produce a new episode of television each week. To behold the degree to which the medium’s aesthetics have evolved, look no further than HBO’s The Night Of. Every set-up has purpose. Every composition is storytelling. The details of each frame – where the people are placed, the amount of negative space, the portion in shadow, the plane of focus – reveal something about the characters trapped within those frames.

Based on the British series Criminal Justice, The Night Of began life in 2013 with a pilot featuring a drug-fueled one night stand between a Muslim-American student (Nightcrawler’s Riz Ahmed) and a troubled trust fund Manhattanite that ended with the girl dead and even Ahmed unsure if he was the murderer. James Gandolfini starred as the suspect’s overmatched, psoriasis-suffering lawyer John Stone, but when Gandolfini passed away the show was put on hold before being revived this year with John Turturro.

With The Night Of’s eight-chapter run now finished – and the show now fully binge-able – cinematographer Igor Martinovic (who shares that credit with Robert Elswit and Frederick Elmes) spoke to Filmmaker about crafting my favorite show of the year. Click on the images below to expand them.

Filmmaker: I’ve read that growing up in former Yugoslavia you and your older brother set up a photography lab in your house.

Martinovic: Yes, when I was little my brother and I took lots of black and white photographs. It was only amateur stuff – what primary school kids could do – but I got hooked by photography and movies. The smell of the chemicals in the lab still appeals to me. It’s a memory that I still carry with me.

Filmmaker: How much older was your brother?

Martinovic: He was two years older than I was. He first picked photography up and I followed in his footsteps and then we would do it together.

Filmmaker: Your parents must have been supportive of the endeavor to give over a room in the house for your lab.

Martinovic: We had just moved to a new house that had an extra room and we were allowed to turn it into a lab. It was something that was encouraged, but they were not involved too much.

Filmmaker: You went to film school in Croatia?

Martinovic: I did, but before college the interesting thing that happened was that in the last two years of high school you had to decide what direction you were going to take, whether you would be an educator or learn a craft or do something else. You basically had to choose. I didn’t know what to do, but I discovered that there was a class in one school that specialized in film and TV. I didn’t even know what that meant really, but it sounded quite sexy to me. So I went to that class for two years and it was eye-opening. It was a fantastic way to be introduced to the film classics because twice a week we would spend the whole day watching and analyzing movies. The school embraced this approach of specializing. So instead of chemistry, we had photochemistry. Instead of physics, we had optics.

Filmmaker: Did many of your classmates end up working in the business?

Martinovic: There are maybe four cinematographers that came out of the class, some editors, some directors. Not everyone, which is often the case in film schools. Some people find their way to film. Some people find themselves in other fields.

Filmmaker: What was a film that made an impact on you during those day-long movie watching sessions for class?

Martinovic: The one that really got me was the Buñuel film The Phantom of Liberty. I had seen it when I was a kid, not really knowing what the movie was. I just went into the theater because it had seductive [lobby cards]. I wasn’t sure what the movie meant, but I was moved by it. The narrative follows one character and then that character gets stopped by a police officer and then we follow the police officer. Then the police officer comes home and we follow his wife. And then from the wife we follow the nanny. It’s an experimental narrative where you become engaged with the absurdity of existence. I saw the movie again in that high school class and I thought, “Ah, so that’s what it meant.”

Filmmaker: What were your options like coming out of film school? The country was in the middle of a civil war. Did you think about leaving and working someplace else?

Martinovic: I didn’t even have my diploma yet when the war started. During the war all the [film school] students went into filming documentaries or working for foreign news channels. That way we didn’t physically have to go into the war, which I personally opposed. I decided to use a camera instead of a weapon. Then the war stopped and there was nothing. It was a complete vacuum. There was no work and there was so much hate. It was enough to push me to go somewhere else, which turned out to be the United States, which was the best solution because my brother was already there.

Filmmaker: Before we get into your work on The Night Of, walk me through a history of the show. The pilot was shot several years ago by Robert Elswit, correct?

Martinovic: Yes. Everything [in the first chapter] until the Turturro character comes into the story was shot three years ago. Then James Gandolfini died and the show was put on hold.

Filmmaker: How did you initially react to the script?

Martinovic: When I was first given the script it hit me immediately on a visceral level. That doesn’t happen very often. I started thinking about how to develop a visual language to support this narrative and the main inspiration for me was the fact that nobody knows what actually happened. Nobody knows what the truth is. I interpreted that into a strategy of obscuring. Just like the truth isn’t visible to any of the characters, I obscured the views so the audience doesn’t always see everything clearly either. We did that using many different devices, including shooting through foreground elements, hiding people in the darkness, placing [characters] on the edges of frames, and hiding things out of focus.

Filmmaker: Most of the section shot by Elswit takes place in one night leading up to the murder that serves as the crux of the story. The rest of the series unfolds within this maze of institutional indifference full of drab grays, greens, and yellows and ugly brick walls.

Martinovic: Some of the monochromatic look of the series goes back to [Elswit’s work] on the pilot and some of it comes from the environments themselves. Once we started shooting in those institutional settings the colors in those places are not so cheerful. I thought a lot about the existing light in those environments. If you put people in a place that is so depressing and so uninspiring, how do you expect them to change?

Those colors weren’t really something we consciously decided to use. We didn’t say, “Let’s make this blue/green or desaturated.” We found that just by pointing the camera at those interiors.

Filmmaker: Rikers Island is nearly monochromatic.

Martinovic: That was a set we built, but it was an exact replica of one of the Rikers wards. That is a credit to [series director, executive producer, and co-writer] Steven Zaillian, who is an incredible researcher and an incredible writer who paid attention to the details of all the locations. When we had to build certain things on stage, they were built exactly as they are in the actual locations. We did sometimes take creative license to be more expressionistic. For example, the police station in reality is really bright, but we made it darker to portray this oppressiveness through the subjective perspective of the characters.

Filmmaker: Steven Zaillian directed all but one of the eight chapters. How does that continuity benefit a show? Even House of Cards, which you worked on, had rotating directors.

Martinovic: Well, I think House of Cards benefitted from the singular vision of David Fincher, who was very involved in the first and second seasons. His imprint was visible in every way. He would watch dailies constantly and give me notes. So in House of Cards even though the directors would change, the look wouldn’t.

With The Night Of, there was a singular vision and everything was driven by Steve’s passionate, guiding hand, but at the same time he was willing to experiment. There are not that many directors out there that would be comfortable with such a level of experimentation in a major TV series. Until recently television was not known for visual experimentation. It was more about just shooting the dialogue. It is kind of absurd to have a visual medium where the words play the most important part. That goes against the nature of the medium, but I think that’s changing. There are people now who are pushing the medium towards its full potential.

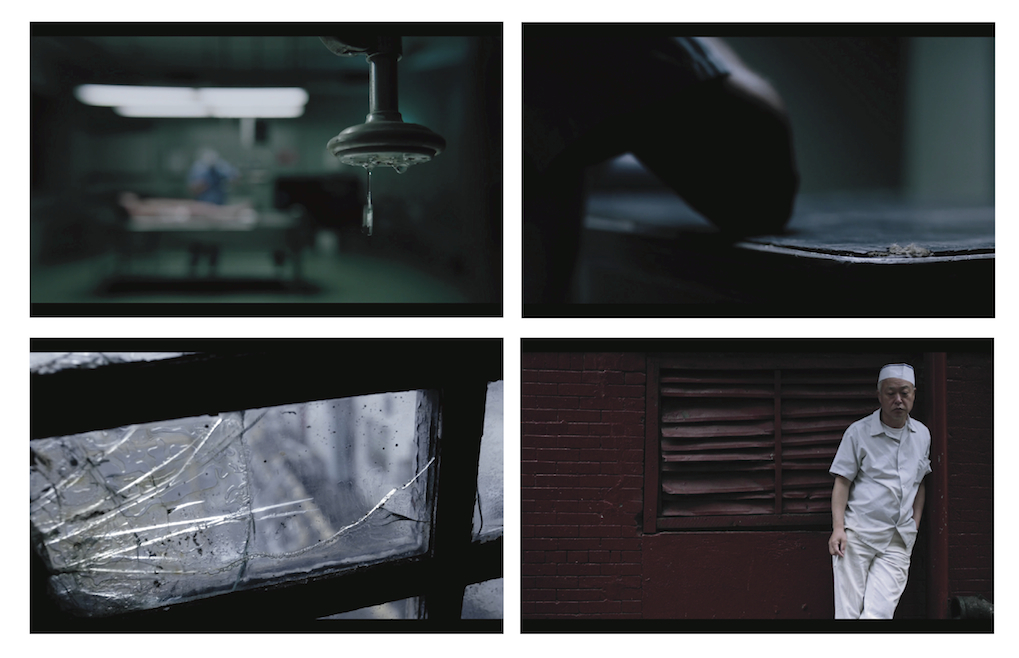

Filmmaker: Let’s dig into these clusters of pictures I’ve put together. Each is a collection of frame grabs highlighting a specific element of The Night Of’s visual style. The first one shows the use of frames within frames.

Martinovic: Boxing people in within the frame is a visual representation of them being captured in a box or a jail cell or even being prisoners of their own life circumstances. As much as [Ahmed’s character] Naz is a prisoner, I think [Turturro’s] John Stone is also a prisoner, unable to break from the box that society has placed him into. That’s one aspect of it. Another aspect is the subjective point of view suggested when observing someone’s existence. That subjective perspective was something Steven Zaillian and I discussed at length – wanting the audience to feel like it’s witnessing the moment right in front of their eyes as well as experiencing the surreal nature of being arrested for something that you don’t even know if you did or not.

Filmmaker: This second group of images highlights the incredibly tactile attention you pay to the texture of the show’s spaces. You talked before about some of the traditional visual limitations of television, but I think one of the benefits of longform storytelling is that you can spend time on these kinds of details.

Martinovic: It’s a credit to Steve Zaillian that he understood that part of the experience of being arrested and going through the system is the way time extends. It passes so slowly that you have time to observe — to see all the details, all the textures. Most of those details were actually incorporated into the shot list. We didn’t discover them on the set. Most were details that we saw when we were scouting. A lot of the frames you are showing here [are recreations] of photographs I took on the scout.

Filmmaker: I love the shot of the cook against that red wall having a cigarette.

Martinovic: When we scouted there was a Chinese restaurant next door. The cook and the wait staff would come out and have a cigarette back there. We just embraced the idea of including them into the scene.

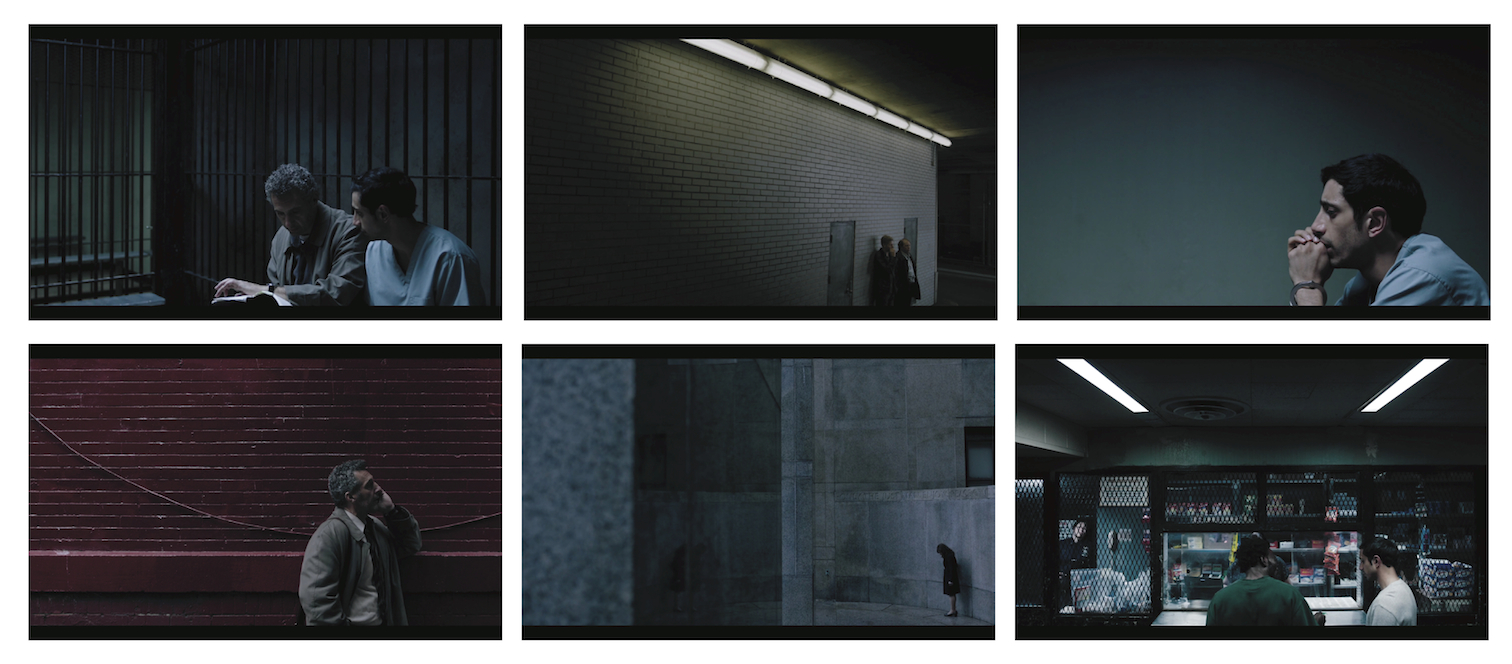

Filmmaker: You also embrace the use of negative space.

Martinovic: Since this story is about an individual who is swallowed into the institutional maze of the criminal justice system, we tried to portray that element by using large empty frames with individuals really small within those frames. We would also place characters on the edges of frames to suggest a sense of entrapment. They are grasping for air as the frame edges are choking them. The overall idea was to employ subjective photography to portray characters’ state of mind – to paint their inner landscape by using visually expressive devices such as negative framing.

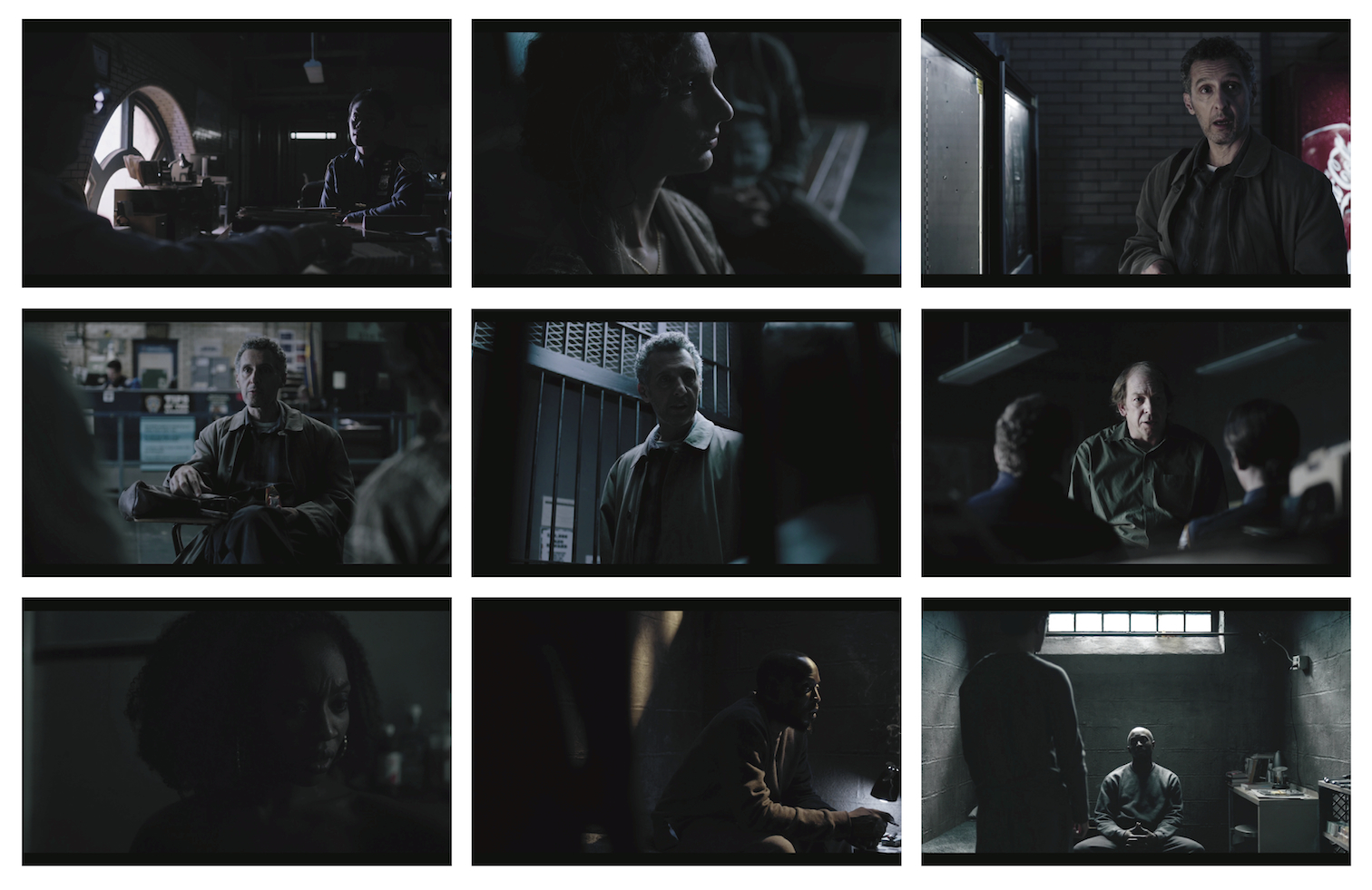

Filmmaker: I chose this last series of frames to illustrate your preference for motivated sources and lack of fill light.

Martinovic: I tend to light spaces, not shots. So usually I light for the space and then we find a way to place the characters within that space in the most appropriate light for a particular scene. For this series the idea was always to use motivated existing light. Many of the images you have here were shot with existing light and then we’d shape it to give it more volume. As the characters are never black or white but rather they represent both spectrums of a moral compass, the look of the series is not just dark or just bright but instead inhabits areas that are darker shades of grey.

Tech Info

Camera: Arri Alexa XT, captured in ProRes 4444

Lenses: Leica Summicrons

Matt Mulcahey writes about film on his blog Deep Fried Movies.