Back to selection

Back to selection

Do Brands’ Lives Matter? Whiskey Fist Director Gillian Wallace Horvat on When Story and Advertising Collapse

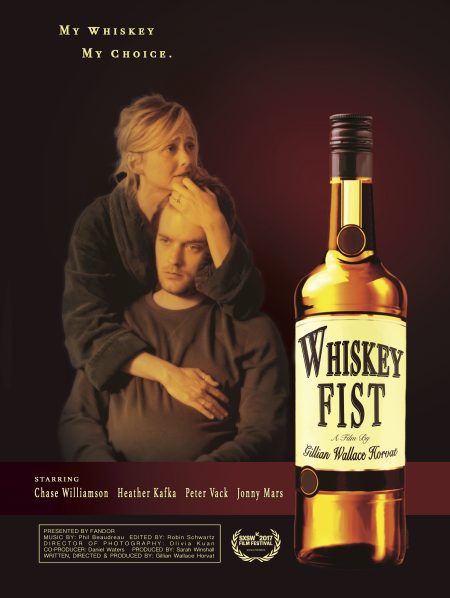

Whiskey Fist

Whiskey Fist In my new short, Whiskey Fist — premiering Friday, September 10 at SXSW — the characters work in front of a sign that reads “Brands’ Lives Matter.” The font is ripped off from Ed Ruscha and the fluorescent ombre background is purloined from posters of the kind stapled to telephone poles advertising local reggae or salsa concerts. Such an insidious combination of high and low appropriation characterizes the vanguard of marketing today, that joking/not joking tone that one would find flourishing in the branding firm where Whiskey Fist takes place. Branding’s sophistication is more seductive than ever, and even more subtle. In the past few years, we’ve even seen their operations spread into historically uncommercial spheres, including the medium of short film. The distinction between story and advertising has collapsed; now it’s all content.

Short-form moving-image sequences have been the lucrative foundation of advertising for decades, but “short films” as we know them from the festival circuit have historically been difficult to fund and, before the internet, had few avenues for distribution. But with the proliferation of smaller screens, shorter attention spans, and an explosion of niche digital platforms these difficulties can now be overcome. Plus, more corporations than ever are interested in funding shorts. That’s a good thing, right?

As always it depends on who’s putting in the money, what their expectations are, and most importantly, how talented the filmmaker is at creatively — or obliquely — integrating a sponsor’s product into the narrative. We’ve returned to the Golden Age of Television, back to The Goldbergs (1949-1957) and the other shows from the 1950s that were the products of collaboration between networks and brands. In The Goldbergs, for example, show creator and star Molly Goldberg came out in character to her tenement window to speak to the audience about the convenience and taste of Sanka.1

Things are only slightly different now when Wal-Mart invites an A-List director like Marc Forster to create a one-minute “short film” (their verbiage) that tells the story behind a Wal-Mart receipt and broadcasts it during the commercial breaks of the Academy Awards. Clearly they’re trying to draw on connotations viewers would draw on from the prestige of the ceremony: Marc Forster is an award-winning director, Forster made a “short film” for Wal-Mart, the Academy gives awards recognizing short film as an art form. If you thought Wal-Mart was just a place you could buy clothing designed by talk show hosts and guns, you’re wrong. They sell culture — and clothes and guns.

Most people reading this article can name examples of non-invasive product placement2 but it’s even easier to name bad ones, like Burger King in Iron Man, or recently one character complimenting another’s Monique Lhuillier dress in 50 Shades Darker. However there’s a distinction between product placement in what is supposed to be a “normal” feature film and the new trend of sponsored content. For the moment these branded films are primarily shorts, some noteworthy examples being the fashion films Wes Anderson directed for Prada starring Jason Schwartzman and Joe Wright helmed for Chanel with Keira Knightley. (Notice how these are both examples of brands building on pre-existing artistic relationships between a filmmaker and an actor to co-opt their creative signifiers.) Superficially, they appear to be ordinary shorts, albeit with high production values and marquee talent. However, the sponsor’s products are featured prominently, so prominently in these fashion films we see numerous costume changes, and the characteristics of the mise-en-scene coordinate with the brand’s current advertising campaign.

Actually, Whiskey Fist does have a sponsor, even with a “presented by” credit. Fandor, the SVOD platform for art films and documentaries, partially provided funding and sponsored a Kickstarter. My previous short, KISS KISS FINGERBANG had such provocative subject matter, I thought I would never find a distributor. Despite having “names” it was never going to be a staff pick or short of the week. Fandor wasn’t afraid to handle it and thanks to them it found an audience. It made sense that they would be involved for my next film. Because of Fandor’s role in the production process I see their funding as getting my back-end up front. Plus there were no content restrictions on my script, no production oversight, no interference. It’s a brilliant model for funding shorts, and I hope it becomes more popular.

There was another key element in our contract — no third party advertising. I was watching a short recently online with an abortion-centered story that’s been doing well on the film festival circuit, funded by a fashion blog. The film started playing and then a pop-up window opened over it with a black-and-white video advertising Lane Bryant’s “#ThisBody” campaign. There was a concentric window around the ad obscuring the abortion short as it continued to play in the background. As filmmakers we sacrifice so much money, time, personal relationships, etc. to telling stories that are personal, that matter to us. Do you think that some of the poignancy of the AIDS drama you’ve been slaving on for five years would be adulterated from the 15-second Fritos ad that runs in front of it, or the in-picture pop-up for Capitol One taking up the bottom third of the frame when the protagonist gets his test results? Don’t kid yourself, ads have an effect on viewing experience. That’s why advertisers pay to put their stuff there.

The reason this tension between art and commerce is even a problem boils down to the tenuous formal distinction between advertising and shorts. 30 second spots and three-minute shorts both aim to communicate to a viewer through moving image and sound, almost always within the confines of what can be construed as a story. In a short: boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy gets girl back. In an ad: Boy meets girl, boy loses girl because of offensive personal odor, boy gets girl back thanks to branded antiperspirant. It’s the same dialectical structure of character, conflict and resolution.

When I’ve spoken to other filmmakers about this issue they often say, “I’m going to take the sponsor’s money but I’m going to subvert the system from within.” Nothing would benefit a brand more. Business historian Thomas Frank writes about “the commodification of dissent,” the ability of advertisers to co-opt the viewer’s feelings of rebellion and sell it back to them through their product. “In television commercials, through which the new American businessman presents his visions and self-understanding to the public, perpetual revolution and the gospel of rule-breaking are the orthodoxy of the day. You only need to watch for a few minutes before you see one of these slogans and understand the grip of antinomianism over the corporate mind.”3 Besides, it takes less energy to buy a DVD of Fight Club than to throw a brick through a Starbucks window.

I’m not trying to say all independently-funded short films are better than every piece of branded content. Martin Scorsese recently made a $70,000,000 17-minute film to promote the opening of a casino in Macao; will any of our best films be as good as his worst? Maybe some of us can beat Shutter Island, but most likely the answer is “no.” As filmmakers the ultimate struggle is to reach our audience and make them feel with us. For those of us who aren’t titans of the field we have enough obstacles to overcome without the visible labels, product mentions, sponsor notes and mandated cuts creating a layer of obfuscation between the director and the viewer. Filmmakers in other countries have national and regional film bodies to fund their work — why can’t we have nice things too? Private arts organizations have been more generous with grants to artists working in the fine arts, often excluding filmmakers from applying. Why the fuck is that? Short film has always been art for art’s sake, so why don’t we deserve the support that other art forms get? Instead of figuring out how to make your biopic about Trayvon Martin organically include Velveeta cheese, let’s work together to expand the pool of funding for short filmmakers from non-profits free of content restrictions.

Unless you’re Martin Scorsese, in which case go make that brilliant Litl Smokies film of your dreams. We’ll watch it, Marty.

1. [For more on how shows aimed at ethnic middle-class audiences like The Goldbergs used their storylines to help viewers adapt to new norms of American consumerism see George Lipsitz’s essay “The Meaning of Memory: Family, Class, and Ethnicity in Early Network Television Programs” in Private Screenings: Television and the Female Consumer.]↩

2. [I particularly admire Kim Sherman’s Ghosting short for Ray-Ban.]↩

3. [From Thomas Frank’s essay “Why Johnny Can’t Dissent” in Commodify Your Dissent: The Business of Culture in the New Gilded Age.]↩