Back to selection

Back to selection

“The Film Gives Viewers Plenty to be Angry About”: Steve James on Abacus: Small Enough to Jail

Abacus: Small Enough to Jail

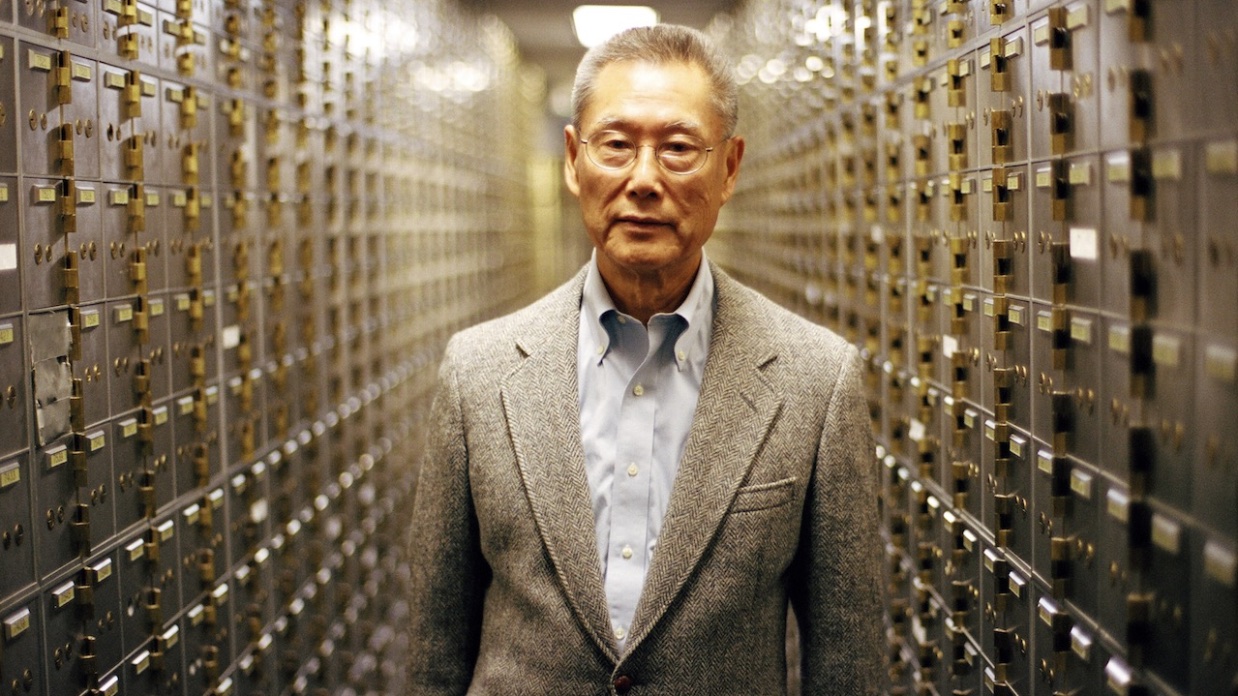

Abacus: Small Enough to Jail Steve James’ documentary, Abacus: Small Enough to Jail, is at once a heartfelt portrait of a close-knit family facing overwhelming adversity and an infuriating indictment of our U.S. justice system gone seriously awry. The film follows the Chinese immigrant Sung family, founding owners and operators of the Abacus Federal Savings Bank down in NYC’s Chinatown, who in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis found themselves locked in a half-decade battle with spotlight-loving Manhattan DA Cyrus Vance, Jr. Though the bank had one of the lowest default rates in the country (with only nine out of 3,000 loans defaulting!), the overzealous prosecutor nevertheless decided to pursue charges — giving the low-income-community-serving institution the dubious distinction of being the one and only bank indicted for mortgage fraud in the fallout.

Filmmaker was fortunate enough to catch up with the legendary Hoop Dreams director right before the film’s May 19th theatrical release at NYC’s IFC Center. James will also be teaching a masterclass co-presented by IFP and DCTV on May 17, for which tickets are still available.

Filmmaker: I believe it was your producer Mark Mitten, who knows Vera Sung, who first brought this story to your attention. Which makes me wonder if you went into production convinced of the family’s innocence from the get-go. Or were you skeptical at any point?

James: From talking with Mark, and also reading the introduction in Matt Taibbi’s book The Divide, where he detailed the indictment against Abacus as an example of the unequal application of justice in America, I came to this story and meeting the Sungs certainly wanting to believe in their innocence. And after spending several days with them, I became convinced of it.

Still, I was very clear with them that we were going to do everything in our power to include the DA’s office in the film and lay out the case against them. (Which we ultimately did.) I took it as a very good sign that this didn’t rattle them. They said they had nothing to hide, nor fear, from our making the film.

Filmmaker: The doc is an infuriating look inside our politically influenced justice system, which also made me think it’s much more overtly activist filmmaking than what I’m used to with your films. Did this feel like any sort of departure for you?

James: I think you are right that the film is a departure in several ways. First, it’s a film that is looking at an overt story of injustice. Most of my films come at injustice, or social issues, more obliquely through detailing the lives of people on the margins of society. All my films have points of view, but often they emerge through the accumulation of scenes and editorial choices.

Abacus was different. Because of what this story was, I felt it was necessary to articulate a clear point-of-view of the film from the beginning. There aren’t, in my view, two sides to this story that carry equal factual and moral weight. However, that didn’t relieve us of the need to lay out both sides to this case. I don’t know that this film is, in and of itself, “activist.” By telling this story, the film gives viewers plenty to be actively angry about. I do think it’s a film that could serve activists, of which I am supportive. And that’s been the case with several of my films.

Filmmaker: New York County DA Cyrus Vance Jr. comes out looking pretty despicable in the doc. And I don’t think he did himself any favors by being so opaque. But was there anyone you wanted to interview that refused to go on camera? Or had to be left on the cutting room floor?

James: We tried, and failed, to get Ken Yu, the DA’s “star witness,” to consent to an interview. That is the one person whose point-of-view I miss being in the film. We also did interview a former federal regulator who was part of the team that evaluated Abacus Bank after it dutifully reported that they’d discovered fraud. But right before the interview, this regulator spoke with his former employers who effectively discouraged him from saying anything of significance to us. I feel that was mostly due to the need for regulators to maintain good relationships with the DA’s office. So that interview ended up on the cutting room floor.

Filmmaker: As a white guy who often shoots in urban minority communities, were there any specific challenges to gaining access to Chinatown that you hadn’t experienced in, say, inner city Chicago?

James: Because I’ve spent far more time in besieged neighborhoods in Chicago, I’ve developed more of a comfort level there. But it’s still true that whether it’s Englewood in Chicago, or Chinatown in New York, the key to access is having film subjects who help you navigate them. When we went around Chinatown in the company of Mr. Sung doors opened. People knew why we were there, and they were supportive of both the film and Mr. Sung because of his revered place in the community.

Filmmaker: The film is full of intriguing twists and turns, but what was the biggest revelation you personally encountered during production?

James: My biggest revelation wasn’t the twists and turns of the case and story, which were indeed plentiful. It was the Sung family. If you handed this story to a scriptwriter and said, “Write a script about a family going through this incredible ordeal that threatens to bring down the family bank,” I doubt the writer would come up with such a winning and humorous bunch. And at the same time, the pressure and anxiety they feel is palpable. The appealing complexity and unpredictability of people, even in times of crisis, is really why I love making documentaries.