Back to selection

Back to selection

Shutter Angles

Conversations with DPs, directors and below-the-line crew by Matt Mulcahey

“They Referred to a Letter They’d Gotten from Spielberg”: DP Caleb Heymann on Stranger Things‘s Season 4

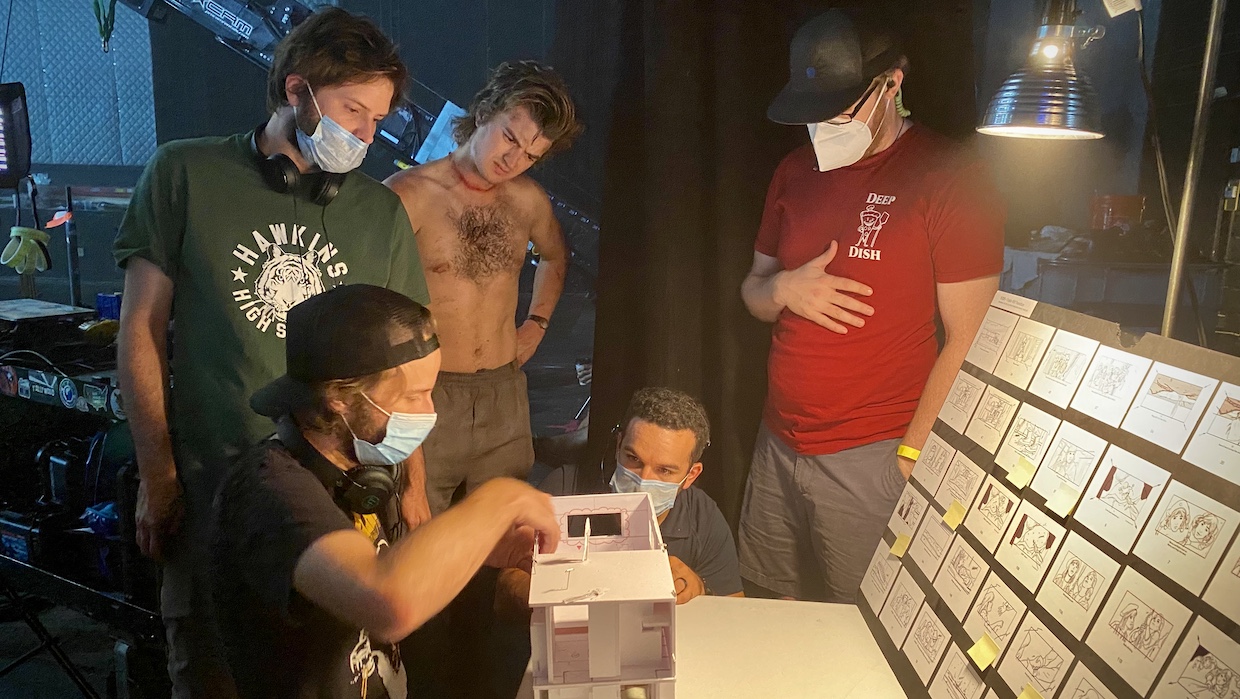

On the set of Stranger Things, season four (photo by Caleb Heymann)

On the set of Stranger Things, season four (photo by Caleb Heymann) In the penultimate season of Stranger Things, the characters find themselves scattered beyond the small town confines of Hawkins, Indiana for the first time, spread out to different, countries and cliques.

Winds of change swept into the camera department as well. After three seasons of Red cameras and Leica lenses, the latest batch of episodes employed the Alexa LF paired with rehoused vintage 1960s glass. The cinematographers wielding those tools have changed too. With original series cinematographer Tim Ives not returning, Caleb Heymann shot seven of the nine episodes, sharing the season’s work with Brett Jutkiewicz (Scream and the upcoming The Black Phone) and Lachlan Milne (a returnee from season three, who also shot the Oscar nominated Minari).

With the first batch of season four episodes now streaming and the final two super-sized offerings coming July 1st, Heymann spoke to Filmmaker about lensing Netflix’s flagship series.

Filmmaker: The last time we talked was for the Fear Street trilogy, a pretty epic shoot that lasted over 100 days. So, you wrapped up photography on that trio of movies in September of 2019. At what point did the offer come to work on the new season of Stranger Things?

Heymann: Toward the end of shooting the 1978 Fear Street film—the second film [released], but the last one we shot. Leigh Janiak, our director on Fear Street, is married to Ross Duffer and we had a lot of the same people working on both—in the art department in particular—and were also shooting in Atlanta. Ross would come to visit set and we got to know each other through that. he had seen a lot of the dailies.

Just as we were about to start shooting, COVID hit in March [of 2020]. We started back up in August and I’d had the scripts for almost a year at that point, anxiously anticipating it and ready to go. The COVID break did provide, from a production standpoint, one silver lining, in that the Duffer brothers got to finish writing the remaining scripts and they just kept getting bigger and crazier with each new episode that would come in—not just in terms of pages and number of scenes, but also in the amount of complexity. Stunts, VFX, the Upside Down and inter-dimensional travel: it was all in there. So, luckily, we had some time over that break to get together and start shot-listing, and I had time to put together lookbooks and moodboards for all these new locations, which was really helpful because there were 800 pages of script to wrap our heads around. I spent a lot of time developing moodboards for each location. I really love that part of the process early on, when you’re free to dream.

Filmmaker: Did it come down to the wire to get this first part of season four done in time for the May release date?

Heymann: Oh yeah. The edit started over a year ago, while we were still shooting, but an insane amount of post work went into this season. It’s thousands of VFX shots and effectively the length of six feature films that the Duffer brothers were working on simultaneously. I know episode seven was down to the wire. When we went to the premiere in Brooklyn where they just showed episode one [a week before the season debuted on Netflix], the Duffer brothers introduced it and said, “We really should not be here right now. We should be back in L.A., because we’ve got like 500 VFX shots that we need to be signing off on.”

Filmmaker: Where else did you shoot outside of Atlanta as the characters scatter away from Hawkins this season?

Heymann: Some of the exterior work for Russia was shot in Lithuania in February of 2020 by Lachlan Milne. My work was centered around Atlanta, which ended up being where most of the season was shot. That included huge stage builds like the Russian Kamchatka prison. Exteriors for the California scenes were shot in New Mexico, outside of Albuquerque. Originally, New Mexico was going to be a huge chunk of the schedule, but in the end it got whittled down to basically just stuff that had to be shot there, because of the impact of COVID on our schedule. We were constantly having to shift things around. We couldn’t just stick with our plan of dealing with distinctive blocks of two episodes at a time. So, having more of the work consolidated into Atlanta made sense.

Filmmaker: The cinematographer credits for the show are interesting and certainly reflect a difficult schedule. There’s multiple episodes with co-cinematographer credits.

Heymann: Yeah, originally it was going to be a little bit more traditional. Pre-COVID, I was going to shoot episodes one, two, five and six, and Lachlan was going to do the rest. So, we were each going to shoot two blocks. On this show, because there’s so much complexity with the amount of work going to go into each episode, and the amount of new locations and stunts and visual effects, it does require prep as you go. So, sticking to this block system made sense for us initially, so that you could have one unit shooting while the other one would be prepping. What ended up happening post-COVID was that Lachlan wasn’t able to finish the show. He had to leave early. So, I took over the Block 4 episodes (seven, eight and nine) and Brett Jutkiewicz came on to take over Block 2 (three and four). For me, it was about a year of non-stop shooting once we started up again post-COVID.

Filmmaker: Where are you based out of when you’re not spending an entire year in Atlanta? Did you get to go home much between Fear Street and Stranger Things?

Heymann: I live in L.A. After Fear Street I made a point of taking a big international vacation where I took over a month off, traveled around and caught up friends. I did that again after we wrapped Stranger Things. It’s necessary to stick to your guns [and take that time off] when the chance comes so that you remember that there’s more to life than shooting films.

Filmmaker: Let’s talk about the process of taking on a show like Stranger Things with a well-established look. You do have the advantage in season four of quite a few new locations, but what aspects of the show’s legacy look did you feel like you had to stay true to, and where was there some openness to change?

Heymann: It’s really exciting to come on and have the opportunity to establish so many new locations and new storylines that take us well outside of the world of Hawkins. In terms of the visual language of the show and what traditions we wanted to continue, the lensing tends to be on the wider end, really putting the viewer in close proximity to the characters and action. We used a lot of 28mm and 35mm, which especially on the larger format cameras give you a pretty wide field of view and a sense of being very close to the actors. It gives an immediacy to the frame but also accentuates the camera movements. The eyelines are generally very close to the lens. When you have an actor reacting to somebody off-screen, the off-screen actor is often basically hugging the camera, straddled underneath the matte box to get that eyeline as close as possible. Those are all things that the Duffer brothers and Tim Ives established as part of the visual language of the show, very much the DNA that we continued on with.

For this season, the Duffer brothers love moving the camera. From our very first shotlist meetings, we talked about doing more oners this year and less coverage. We really wanted to make use of moving masters, where the shot starts as one thing—a detail of a car whooshing by, a phone getting slammed—and then pivot around and develop into a medium two shot that might hinge into a profile closeup, then later pull out into a wide shot. That doesn’t mean that we weren’t getting additional coverage for the scene, though. Steven Spielberg, who of course is a huge influence on the style of the Duffer brothers, is such a master of blocking actors to camera and how that dance is choreographed. With each season, the Duffer brothers have gotten more and more masterful at that as well. For this season that meant that often we’d be shooting these shots that moved around 270 degrees, sometimes even a full 360. As a cinematographer, I love that challenge, because it really keeps you on your toes with lighting. It’s not just about making it look good in one direction. You have to make it look good in all directions and also keep your lights out of the shot. We were also very lucky to have such incredibly talented Steadicam operators on board in Nick Müller and Ben Semanoff.

We also had more handheld this season, something that hadn’t really been part of the aesthetic of the show before aside from maybe some fight scenes here and there. With regards to the lighting and the color palette, the Duffer brothers definitely wanted to get back to a bit of a more retro, slightly bluer hue to the moonlight. They referred to a letter they’d gotten from Spielberg where, I guess amongst other things, he’d specifically mentioned loving their retro callback to that blue moonlight in the first season. How can you argue with that?

Filmmaker: Did the Duffer brothers have a list of reference films they wanted you to check out?

Heymann: I was expecting there to be more of that, but it wasn’t actually much of a thing. We would talk about specific films for specific moments and sometimes do a little rabbit hole down YouTube trying to find a particular shot. For example, the very first shots of episode one are referencing this YouTube clip that’s actually called “I Was a Great Newspaper Boy in the ‘50s.” When the Duffers were initially sort of pitching the season to me, they talked about it having elements of A Nightmare on Elm Street, Hellraiser and a bit of Evil Dead. So, as I was reading the scripts, I started going back and rewatching some of those films, in particular the third Nightmare on Elm Street movie Dream Warriors, which takes place in 1986, the same year as this season. That was a big touchstone influence. You see it right away in Chrissy’s house at the end of episode one.

Filmmaker: After three seasons of shooting on Red cameras, the new episodes have switched over to the Arri Alexa LF. What prompted that change?

Heymann: Lachlan and I tested the Arri LF against the Red and tested about seven different sets of spherical lenses. It’s always been a spherical show, which helps the camera get super close to the actors without using diopters. The decision to shoot on Alexa was driven mostly by our experience with that camera and the reliability that it offers, as well as its beautiful highlight retention and how it handles color contrast in underexposure. Originally, the decision to shoot Red for the show had a lot to do with Netflix’s 4K requirement. At the time in 2016, there wasn’t a 4K Alexa option. That said, each season had been shot on a different sensor anyway. Season one was Dragon, Season two was Helium, and Season three was Monstro. So, three different flavors of the Red sensor. Our colorist Skip Kimball showed us after our tests that the classic Stranger Things LUT—it’s always been a single LUT show—was quite easily achieved on the Arri camera as well, shooting ArriRAW. We’re kind of at a point in time where all these cameras are so good. I’ve shot a lot on Reds. I’ve gotten great result from Red cameras, too. What defines the look of a show has a lot more to do with the lighting and to some extent the lensing [than what camera you shoot on].

Filmmaker: And you changed lenses as well?

Heymann: In years past it has always been a Leica show. This time, we ended up going with some vintage rehoused lenses, primarily Canon but a mixed set of vintage lenses from the ’60s. There were twelve primes in total that gave us a lot of choices for the wide to middle range of focal lengths. Our camera house was Keslow Camera in Atlanta, but we also got to work with Camtec, another great rental house based out of L.A. They gave us some rehoused Falcons, these customized lenses only available through them that were originally developed for Bradford Young for Solo. They’re great because they’re lightweight, small and they’ve got great close focus. Some are very unique—the 45mm is a favorite lens of mine. It’s super fast and has a very dreamy look when you shoot it wide open. So, you’re able to either shoot everything at around 2.8 and get a pretty consistent look across the set, or go a little bit more open with certain focal lengths and get something a little bit more abstract. We also used Lensbabies for some of the hallucinatory moments with Eleven in the missile silo and in the Hawkins lab.

Filmmaker: Going back to the references for this new season, the most Elm Street-esque sequence for me is the first episode scene in Max’s trailer park, where we first meet the new villain, Vecna.

Heymann: For the trailer park exteriors we really leaned into the color contrast you get between sodium and mercury lights, where you’ve got the really deep orange of the sodium against the cool cyan of the mercury lights. That trailer park was a giant set, so we came up with a plan to checkerboard those light sources so you would always be seeing one of each [color] in frame. That also meant once we got inside of Eddie’s trailer, we’d already established the mixed color temperature thing happening outside and could carry that inside, with cyan light coming in from the windows mixed with really gnarly greenish fluorescents and warmed up tungsten practicals.

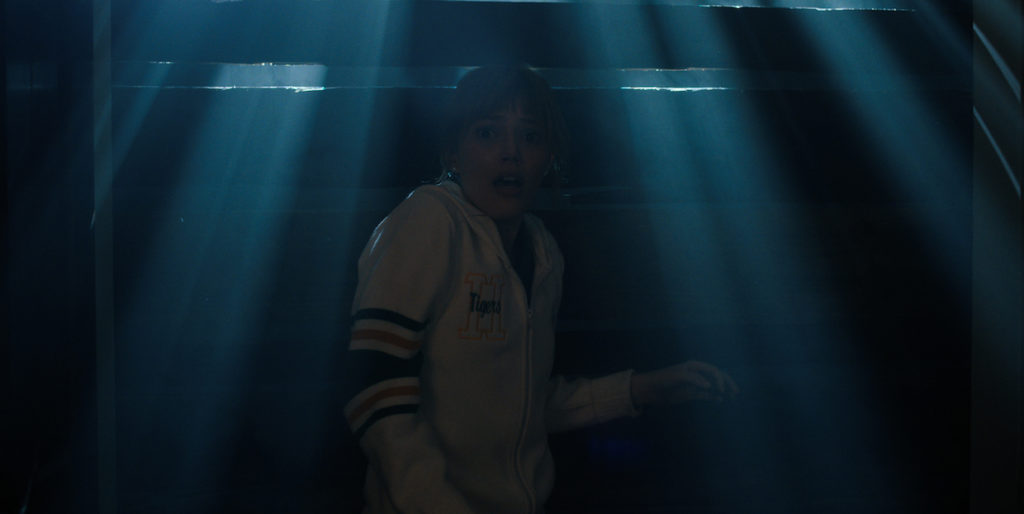

Then we transition into Chrissy’s nightmare.We wanted to use this idea, like in A Nightmare on Elm Street and some scenes in Hellraiser, where the reality almost seamlessly transitions into the nightmare. Once we’re into the nightmare version of Chrissy’s house, the lighting starts getting more and more theatrical, and by the end there’s these crazy shafts of completely unmotivated blue light coming in from windows. You’re kind of questioning, “Does this look too much like a shitty old ’90s music video?” [laughs] We talked about really leaning into the more retro horror style for those scenes while still trying to keep the rest of the show more grounded, which is important when you’re dealing with all of these supernatural phenomena. You want things to visually feel grounded, but we weren’t afraid to have some fun and be bold with the lighting.

Filmmaker: One of the iconic shots from the original A Nightmare on Elm Street is Tina on the ceiling, which they accomplished by building the set on a gimbal that could be rotated. You have a similar effect in that trailer park sequence with Chrissy. How did you pull your shot off?

Heymann: We shot some of that trailer park scene at a practical location, but for that shot we were on the stage version of Eddie’s trailer. We were able to do that effect with just stunt rigging. We had both Grace Van Dien, who plays Chrissy, and her stunt double suspended in a harness. Grace was able to do the initial levitation practically in camera, then her stunt double hit the ceiling. It was more a matter of how long [the actress] was comfortable being up there in a really uncomfortable position, ratcheted to the ceiling. You could only really shoot for ten seconds or so, then we’d need to let her down and give her a break. When the stunt double ratcheted up to the ceiling she hit it so hard the whole trailer shook. So, fortunately we got that in one take. It’s only when you get into the last couple shots with the twisted limbs where VFX takes over.

Filmmaker: Episode seven begins with an extended sequence in the Upside Down, this sort of mirror dimension intertwined with Hawkins. How do you create the Upside Down look, with its blue ambiance?

Heymann: That features, basically, a five-minute long walk and talk. The Duffer brothers really wanted to be able to shoot it uninterrupted, so we had to light up enough forest so they wouldn’t have to cut. We walked out [the route] with the script and figured out about how much forest we were talking about. Interestingly, that was the first thing we shot from Block 4 [of episodes seven, eight and nine]. Because of the curveball of COVID production, we weren’t able to shoot any of the big crowd scenes early on. So, we actually did that opening of episode seven in the Upside Down when we were shooting the Block 1 episodes, just so we would have something to shoot without crowds. So, that got pulled up and shot completely out of sequence, which is a little scary because you lock yourself into some things continuity-wise and it was the biggest stretch of Upside Down lighting that had ever happened on the show.

It was quite a task to light about six hundred feet of Upside Down forest for the actors to walk knowing we’d be looking in all directions. There were at least six Condors lighting the background and about 12 helium balloons. The Upside Down, from a lighting standpoint, is kind of this liminal space between a normal moonlit night and a bit more of a twilight look, where you do have a certain amount of rich blue light coming from the sky. The sky is dark, but it’s still luminescent. So, it does require a lot of balloons to create that look. You have to figure out where you are going to hide all these helium balloons and which trees to tie them down to. We also need to account for the red lightning flashes in those scenes. It ended up being quite a rig.

Filmmaker: What were the units?

Heymann: We used SkyPanel 360s with a Vulture, a moving head that allows [the unit] to pan and tilt remotely. In Atlanta, the weather can change so quickly and you don’t want to have to send up people to man these Condors unless you absolutely have to. Fortunately, we’re in an era now where we could have the 360s remotely pan and tilt, then we would have a couple of these SolaFrame 3000s with moving heads. That allows you to do everything from the ground: pan and tilt, flood and spot, throw in gobos. That could all be controlled by the board operator without having to physically go set something up. We could hit somebody with a backlight or throw a highlight into a background, all at the touch of a button. There was also a unit called the Chroma-Q Color Force that was pretty useful when we needed red lighting to carry longer distances.

Filmmaker: What do you want to finish up with? Any other scene you want to talk about?

Heymann: One of the main challenges to deal with was all the work around the water and underwater, the stuff out at Lover’s Lake. There were a lot of conversations about where to shoot that, because we had the location of the boathouse actually on a practical lake. We actually had to go back to that location a couple of times based on the temperature of the water and the way the trees looked. Initially, the water was too cold for the actors to actually get in, then there was also an issue around wanting the trees to not just be completely dead in winter. So, we had to come back and shoot certain angles when it was closer to spring and there was some vibrancy to the trees.

That water work was like all the worst things to deal with happening at the same time—shooting around water, doing it at night, dealing with stunts and having minors. Episode six necessitated building a water tank for certain shots. So, we were able to get a water tank built on stage to our specifications and that allowed us to do both the underwater stuff that we needed, but also had the additional perk of giving us more control for some of the stuff that happens on top of the water as well. The complicated thing was then matching the topside stuff—shot on two different practical locations in two different seasons around this lake—with what we were doing on stage. The look of it and the different eyelines all had to match up. We had to storyboard that stuff pretty carefully so that we didn’t completely drop the ball. It’s just always a challenge when a single scene is getting broken up and shot over so many months, but hopefully you never notice.