Back to selection

Back to selection

Extra Curricular

by Holly Willis

Better Living Through Cinema

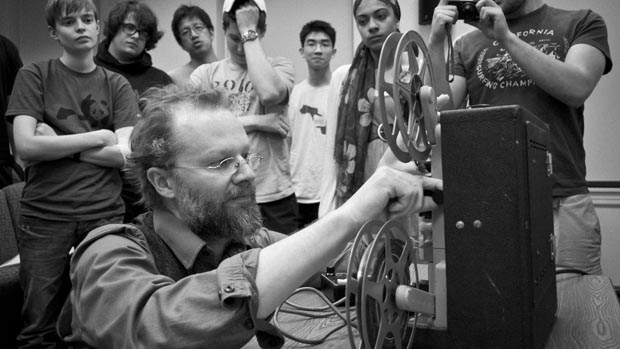

It’s a Friday morning, and David Gatten is very tired, having taught both Wednesday and Thursday evenings. Like many filmmakers, in addition to making movies, Gatten also teaches. Indeed, the experimental filmmaker boasts the title “Lecturing Fellow and Artist in Residence” at Duke University’s Arts of the Moving Image program, where he lectures during the spring semester, before returning to the old mining cabin in Colorado’s Four Mile Canyon where he lives with his wife — filmmaker, writer and editor Erin Espelie — for the rest of the year. His courses? AMI 101: Introduction to the Arts of the Moving Images: Better Living Through Cinema, which is based on the idea that films can show us how to exist in the world, and AMI 370S: Matters of Life and Death, which explores the most intense experiences humans endure.

Gatten, who is known for a body of films dedicated to discerning the very essence of cinema, isn’t simply showing movies and lecturing on the history and theory of cinema. Instead, he’s bringing the rigor and attention to creating an indelible experience that characterize his own filmmaking to the structuring and presentation of his courses. For Gatten, teaching a course is a deeply creative act.

Take his syllabi: each starts with a collage of quotations. For Better Living Through Cinema, there’s a snippet from Rebecca Solnit on how to get lost, a poem by Norma Cole about false maps scrawled by sleep, a pithy statement about form and aesthetics from Fredrick Sommer and an eloquent analysis of spectacle by Guy Debord. The Matters of Life and Death syllabus features quotations from the writings of Maya Deren, John Cassavetes, Geoff Dyer and Henry James, among others. The words are more provocative than instructive; they ask you to enter the experience of the semester with curiosity and attention.

“I almost never introduce the film by talking about the film,” says Gatten about each class session. “I introduce the film by reading philosophy or playing a piece of music. The students don’t know why I’ve done that until 30 minutes into the film, when they start to understand why they got this other information.

“I do think of these as compositions,” Gatten continues, explaining his philosophy of both each class session and the structure of the courses across a semester. “The courses are intellectually and artistically satisfying in the same way that making a movie is. It’s like working in the long form of 14 weeks.”

Gatten explains that his students are not film students — there is no major in film at Duke. “They’re not coming to get job skills,” he says. Instead, students who enroll learn about ethics and aesthetics. “In Better Living Through Cinema, we’ll look at 27 different films, from three-and-a-half minutes to four-and-a-half hours in length, all different kinds of work, from Hitchcock to Painlevé. Last night we watched Window Water Baby Moving by Stan Brakhage and Claire Denis’ L’Intrus (The Intruder), a 13-minute film about birth from 1958 and a 130-minute, first-person film about a heart transplant. That’s the kind of combination I like to put together.”

For Matters of Life and Death, Gatten has tried to view the entire semester as a structure in itself. He explains that the course focuses on instances in which filmmakers deal with extreme subject matter. “They must resort to extreme formal gestures to really deal with the content,” he explains, “and I believe the films accumulate in a certain way week to week.” Gatten explains that the first and 14th weeks of the semester speak to each other. Then the second and 13th weeks also speak to each other, and so on. “The class sessions are like a series of nested parentheses, and they build to a core at the center of the course.” He adds that for each session he writes a 14-page essay, which he then memorizes and presents as a monologue. “We meet for class from 6:00 to 10:00 p.m. Then we have a dinner from 10:00 to 2:00 a.m., when there is discussion.”

Gatten links his efforts in designing and presenting his courses to his own work, which consists of a collection of short films that he began making in 1999, several of which are part of a nine-part film cycle, Secret History of the Dividing Line, based on William Byrd II, his 1728 book The His tory of the Dividing Line Betwixt Virginia and North Carolina and his vast library. Gatten’s films are about reading, writing, thinking and knowing, and they deal explicitly with the material of film — emulsion, light and dust, for example. In 2012, however, Gatten also made a three-hour digital work, The Extravagant Shadows, that invited the artist to explore a new form of writing and cinematic composition, as well as more extreme forms of duration.

“I don’t think I could have made a three-hour movie without having done these courses,” Gatten says. “Almost for the first time in my life, the way I’ve been thinking about structuring the classroom space into these four-hour blocks and the way I was thinking about structuring a long movie started to align. They started to feed each other.”

Having viewed much of Gatten’s body of work in Los Angeles last October as it traveled across the country as part of Texts of Light: A Mid-Career Retrospective of Fourteen Films, organized by Chris Stults of the Wexner Center for the Arts, and having had several conversations with him about films and filmmaking, I can’t help but envy a group of undergrads in Durham, N.C.,right now.