Back to selection

Back to selection

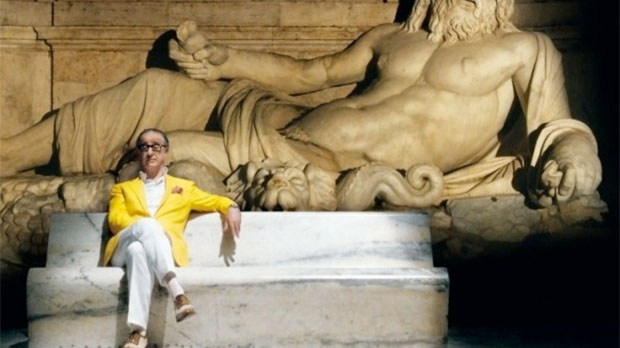

“The Misery of Some People:” Paolo Sorrentino on The Great Beauty

The Great Beauty

The Great Beauty Since its premiere at last year’s Cannes Film Festival, Paolo Sorrentino’s The Great Beauty has enjoyed much critical and theatrical success — alongside the more unwanted La Dolce Vita comparisons and projected criticism of the Berlusconi era. In speaking with the filmmaker behind this alternately bombastic and meditative examination of a writer adrift in the eternal and ostentatious city, however, one senses that Sorrentino’s intentions were not nearly as biting as some have gathered. Yes, there is a Bishop more infatuated with food than God, a woman who strips for the love of the profession, a child who earns millions by having a temper tantrum on a canvas, but these are all, Sorrentino suggests, heartfelt amusements more than caustic critiques. Above all, The Great Beauty strives to find the loveliness beneath the surface.

Filmmaker: The film has a near novelistic structure. It’s a character study, but it also deals with an ensemble and it’s a portrait of a particular place and time. How did you sort of craft those distinct planes in writing the script?

Paolo Sorrentino: If you think it worked, I was lucky. The structure, as you said, is the structure of a novel. That’s the way I set out to structure the film. It follows the evolution that a novel would follow and it borrows a lot of elements, stylistically of what a novel would be like. For example, the length of each scene, or the fact that there’s all kinds of deviations or side stories, or the introspection of the main character, that’s very novel-like and so, yeah the novel-like style was what I’d call a lighthouse guiding my work.

Filmmaker: What was your entry point? Was it the character of Jep (Toni Servillo), or did you start with the bigger picture?

Sorrentino: Well, first off, I had a lot of notes on the world around the main character, and I didn’t have a main character — I just had all these observational-type notes and then I found this character that could navigate well these worlds, and then I moved on to the emotional component of the story. So that’s the approach.

Filmmaker: For me, the film is very interesting tonally, because there are some sardonic elements, but it is also emotionally heavy at times. There are a lot of scenes that can be read as critiques of modern Roman culture: the absurdity of Talia Concept, the performance artist, the child who paints, the basement botox scene. Were these intentionally included as ironic depictions?

Sorrentino: About the botox culture or a certain type of performance art, first of all, I’d like to point out, I don’t think it’s just Roman, it’s really across the border, it can be found in many other situations and many other worlds. But my attitude about those things is mainly, not critical as such, I don’t even think I’m all that critical in the way it’s depicted. I think my outlook towards those worlds is more of a surprise or amusement to some extent. These are all forms of the modern world, of modernity, that I don’t think should be criticized. I think they are because I see them as an expression of human weakness and/or human frailty. For example, you know, the botox culture, wanting to preserve youth at all costs, or wanting to be an artist at all costs, even though one doesn’t have the talent or caliber for it. This is something that’s very human and it’s something that I may smile at, but the smile that’s full of tenderness.

Filmmaker: There’s a sense of loss throughout the film. When we first get a sense for Jep, his true person, is when he learns of the death of his first love. There’s the whole notion of him having been this one-hit wonder with the publication of his only novel, but he seems to be okay with that. Something that I was curious about is how in our current society, which is not just exclusive to Rome, but it moves so quickly, it carries a great pace. How do we continue to uphold what was important to us in the past?

Sorrentino: It is very true that the movie is a lot about loss, actually with the passing of time, so many things fade away or get lost. But you were saying in your last comment or I guess it was a question, ‘How do we uphold the things that are important to us?’ I wish I knew, if only. You know, I think upholding what is important to us is indeed what one should strive for. A person can be called mature when they learn to be more selective, when they learn to only hold on to those things that are truly important, when they learn to distinguish what is and what isn’t and when they manage to free themselves, rid themselves of what is not essential. But how that is done? I wish I knew.

Filmmaker: One of my favorite scenes in the movie is when Jep dresses down Stefania and puts her, which also deals with the passage of time, as it can present the opportunity for self-reinvention. She has this deluded image of herself, but Jep is able to get to the truth of it right away. I guess this isn’t really a question, but I liked how you did that.

Sorrentino: [Laughs.]

Filmmaker: Is that what sets Jep apart from everyone else — that he’s so honest with himself about his personal history?

Sorrentino: Yes, that’s probably the way it is. Maybe, that scene, I don’t know what I can add. What you said was right.

Filmmaker: Something I wanted to ask about are the religious aspects in the film that come out especially towards the end, with the a saint and the bishop, because I feel like American audiences, or foreign audiences, maybe don’t necessarily know how to read them in the way that an Italian one would. To me, at some points, it plays like satire, but then at the end, there’s a very profound moment Jep shares with Sister Maria. He is there to interview her, but she sort of turns the tables on him. Is there a clear way that we’re supposed to understand this religious character?

Sorrentino: The Saint and the Bishop characters are there because in that context, the protagonist, Jep, uses irony and makes jokes against them the way he does, against everybody else around him, that’s his weapon – irony is his weapon that he uses to limit and to turn people around him into smaller people, to put people in their place and to really limit them, and the only time that this strategy, this coping strategy that he always utilizes doesn’t work, is with this Saint, Maria, because that person, the Saint, was more powerful than his irony ever was. And basically, this allows him to set this coping strategy, based on irony, aside and to start asking himself true questions. So, rather than talk about a religious component in these characters, I would focus on the fact that this 100 year old woman has managed to really distill her existence into what is truly essential, truly fundamental. And she only says vital things, and therefore, these things are very simple. And this clashes with or happens at the same time as the crisis that the main character goes through and he was living this life that was so interconnected with emptiness and this meeting with this person triggers the resolution of this crisis, and the crisis was linked to the fact that he felt that emptiness or nothing envelops his life.

Filmmaker: Right, yeah, that’s interesting. I’m curious though how, especially with the bishop, because he loves to derail every conversation into food and recipes, if in Italy, if that’s being read as some sort of underhanded critique of the Church. I mean, I don’t think that, but I don’t know how it’s viewed at home.

Sorrentino: Yes, some people did read it that way, but it was not like that at all from me. If I wanted to criticize the Catholic Church, there would be so much more material. You know, the Bishop talking about food is nothing — it would be, things that are a lot more troubling. Sincerely, having a Bishop that talks about food all the time, is very funny to me and I like to make people laugh, and so that’s why I did that.

Filmmaker: Who, or what, for you is the great beauty?

Sorrentino: Everything is the great beauty. A little bit of everything: the city itself or the misery of some people or the greatness of people that can build or create a city like that. If one takes one’s look away from people as such, and turns it into all that is round, everything has beautiful components, and that’s what the film sets out to do, to try to find the beauty everywhere.