Back to selection

Back to selection

“Just Because It’s Not Online Doesn’t Mean it Doesn’t Exist”: Tips on Finding and Using Archival Footage from DOC NYC Pro

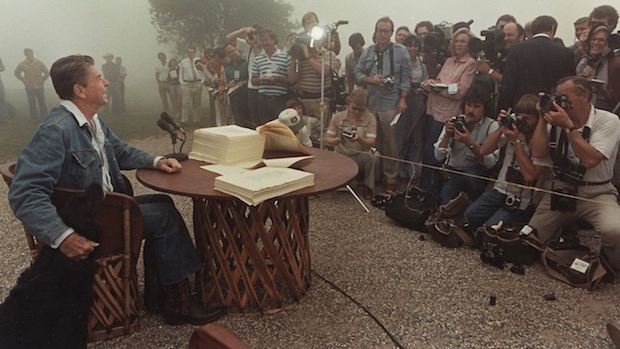

The Reagan Show

The Reagan Show Sitting in the audience at a DOC NYC Pro Masterclass just days after the election, I found it impossible to separate the discussions and stories from the story of our country at this moment. Everything going on in film seems so important and relevant to how we see ourselves and the world, and nowhere do we see this as directly as in documentary. This was brought home by producer, director and archivist Sierra Pettengill (director, Town Hall; archival producer, Kate Plays Christine) in a panel taking place Sunday, November 13 called “Getting Creative With Archives.” Pettengill showed a clip from The Reagan Show, the documentary she’s directing with Pacho Velez, in which the former president pardons a Thanksgiving turkey. It’s pure performance, the sort of innocuous, camera-ready act that politicians occasionally engage in to remind us that they are just normal people like us and that everything is okay. These acts are rituals of normalization, the same sort of thing that People magazine and other publications have taken heat for in recent days in regard to Donald Trump’s bigoted speech and impending inauguration as President of the United States.

Pettengill says she and Velez have been working on their film for three years, and that the turkey clip was found in the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library at the National Archives. She noted that the footage is public domain: “This is our footage, we all own it, and [with it] we are able to show that the skills of a performer and actor are the skills that Reagan brought to the Presidency.” She continued, “I’m thinking a lot right now about the office of the Presidency, and how, in the times we’re in now, we can look back to history to figure things out.”

Matt Wolf is the director of Teenage, a history of youth culture. It was a film that was always conceived of as utilizing a lot of archival material. The archival team, which included Pettengill along with Rosemary Rotondi (archival researcher, The Freedom to Marry, CITIZENFOUR) came on very early, and the material they found informed the development of the story.

When making a film that’s reliant to some degree on archival footage, Pettengill advises that it’s important to give yourself a long lead time. Building relationships with archival sources can take years, and it can be more cost-effective to negotiate footage rates early in the process. If you only start as you’re nearing the end of the process, it tends to be more expensive because you’re putting out fires instead of making a long-term rate plan for your budget and staying on top of it as you go.

Rotondi agreed: “The more you develop relationships with the archives, it makes a big difference — many archives have minimums, and then they’ll start to negotiate, but that can be a long process.”

Archival researcher and producer Amy Schewel (Soundbreaking: Stories from the Cutting Edge of Recorded Music) added that sometimes rates go down the longer filmmakers have a relationship with a particular archive. While companies can implement rate increases over time, they will also sometimes cut breaks for filmmakers whose seriousness they are impressed by and whose projects they’ve become emotionally involved with. Adds Wolf, forming relationships with the archives that may be providing footage to your film is as important as forming relationships with subjects or funders.

The panel’s moderator, Karen K.H. Sim (editor and producer, Nothing Left Unsaid) brought up archival materials as really being a creative issue of coverage: “There are a lot of stories you’re going to want to tell, and you’re not always going to have literal coverage of it, so you have to think of creative ways of telling the story.”

Schewel suggested using as illustrative footage something that’s not necessarily the literal thing being discussed, but something evocative of it. She also reminded that film is not just footage — it’s audio, it’s ephemera, it could be a page from diary, a map, a poster or illustration, a headline, a newspaper article from long ago, illustrated manuscript, or any still image that is not a photograph. And then, of course, there are also home movies and snapshots.

As the panel neared a close, the conversation returned to the topic on my and most people’s minds right now: the election and this moment in our history. The idea was raised by Sim that if history repeats itself, the ways in which we participate as filmmakers and people is going to be important.

On that point, Rotondi had a surprising tip about approaching sources: sometimes calling yourself a documentary filmmaker can be a bad thing. While working on Inside Job, she called the Federal Reserve to get a copy of a paper written by a subject of the film. She initially identified herself as a documentary filmmaker. They hung up on her. A few days later she called back and just said she was looking for a paper because she was researching the subject and his work, and she was immediately directed to an obscure internal website that had published the paper.

Rotondi also reminded that the National Archives in Washington, D.C. is a valuable resource. While there are transfer costs, the footage itself is free, and these materials can replace more expensive footage a filmmaker might otherwise license. However, the National Archives does not have that much digitized or already online, so filmmakers either need to hire someone who works there or go in person. Either way, going there first will likely save money as commercial libraries may be licensing the same footage, but not for free.

And Sim had one other important and final reminder: just because it’s not online doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist.