Back to selection

Back to selection

Storytelling, Memory and Alternate Worlds: Michael Almereyda on Marjorie Prime and Escapes

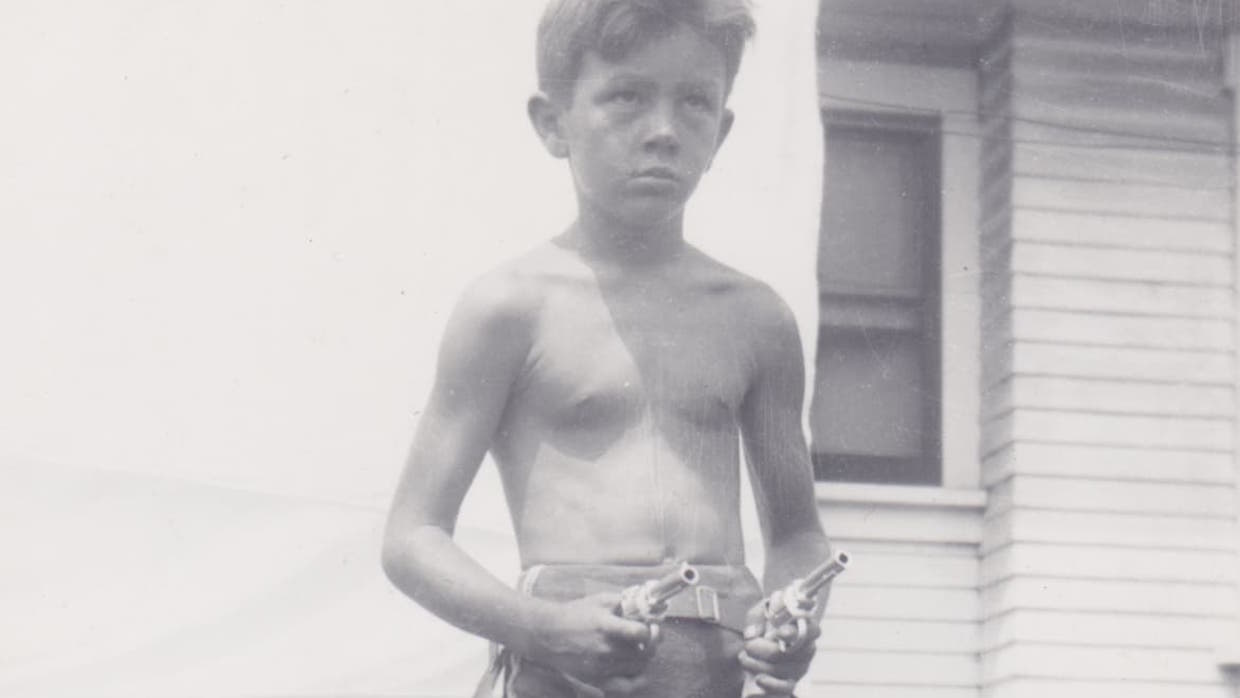

The young Hampton Fancher in Escapes

The young Hampton Fancher in Escapes Michael Almereyda has two films this year, the curiously rhyming duo of Marjorie Prime and Escapes. The former, as I wrote from Sundance, is “a heavily modified adaptation of Jordan Harrison’s play, customized to fit the ever-adventurous Almereyda’s tastes and frames of reference. The premise is both simple and tricky: in the future, your deceased loved ones can be brought back as holograms for company. Marjorie (Lois Smith), aging and losing her memory, has her late husband Walter (Jon Hamm), eternally in his 40s, for company, a development which makes her daughter Tess (Geena Davis) a little nervous. From this low-key sci-fi premise, Marjorie gets complicated — best to keep the rest under wraps.” Escapes cedes the screen to screenwriter/director Hampton Fancher, who tells some very long, extremely entertaining anecdotes from an adventurous life to the visual counterpoint (don’t call it an illustration!) of still photos and films/TV shows from his life and those of his friends. Escapes opens today at NYC’s IFC Center, with more dates to follow; Marjorie follows on August 18th, with a limited NY/LA release followed by an expansion. I met Almereyda last month to dive into both.

Filmmaker: I don’t know if the two projects were parallel or converged at a certain point. They’re coming out at the same time, but that doesn’t mean anything.

Almereyda: The first scrap of footage for Escapes was from November of 2012, so it’s been a long time in the works. I asked Hampton to recount a story about the making of Blue Hawaii, a breezy Elvis movie in which Hampton’s girlfriend at the time, Joan Blackman, was co-starring. Joan Blackman’s the one Hollywood starlet who didn’t sleep with Elvis. The story Hampton told was enjoyably outrageous, and I wanted to make a short out of it, using Hampton’s voice running parallel with clips from Blue Hawaii, describing things you couldn’t see in the movie. But as Hampton told more stories, I put that one aside. I began to feel there was a structure, a mounting point to putting certain stories together, and this had to do with how Blade Runner almost never happened. It could have been easily derailed — Hampton’s life could have been cut short, the project could have eluded his imagination. But as Escapes found its shape, I saw episodes winding along this improbable path towards Blade Runner. That became the organizing structure.

Filmmaker: You started in 2012. How much time did you spend purposefully filming him?

Almereyda: Not much, maybe five visits. We’re friends — I see him all the time, and occasionally it made sense to fill in a blank, sharpen a corner. The movie was self-generated, almost a hobby, constructed in the editing. Nobody was going to finance it, or watch as many episodes of Flipper as I was willing to do. And I wasn’t really watching them, I was fast-forwarding — I knew the sorts of images I wanted. At any rate, I enjoyed it — delving into this foreign matter, finding young Fancher adrift in obscure TV shows, then sharing the images with my editor. I’ve compared it to making a bird’s nest. I tend to bristle a little when people say we’re illustrating Hampton’s stories. An effort was made to go against the grain of the stories, to open and subvert them, with images circling around what he’s saying, or veering off altogether.

Filmmaker: That’s maybe a good way to loop back to Marjorie Prime. In Late August, Early September, there’s this line where a woman who’s very angry tells a man, “Time, History, Memory — these are just words.” The idea of capital-m Memory often seems vague, but in Alain Resnais’ films it’s very concrete — there’s an actual scientist in Mon Oncle d’Amerique and fictional scientists in Life is a Bed of Roses. Did that inform your thinking?

Almereyda: I want to believe there’s an affinity, but I don’t feel I’m a student of Resnais. These two movies, and others I’ve done, are related to memory because I think it’s a central component of consciousness and life. I don’t remember that part of Olivier’s movie, but to me, time, history and memory are hardly abstractions — they’re like eating and sleeping, essential parts of being alive. How you lean on memory, avoid it, share it – this is all very human and particular. So I don’t see myself hanging onto Resnais as a handrail, or even as a conscious reference. I showed [DP] Sean [Williams] Muriel when we were setting out, and he got impatient it. He didn’t like the lighting. He prefers William Fraker. We also spent a fair amount of time looking at films by an earlier, unscientific Frenchman, Renoir.

Filmmaker: How did the play come to your attention? Are you a regular theater-goer?

Almereyda: No. I tend to go to plays that my friends are in, and Lois is one of them. She was so excited about this play, describing it before it was produced, so I was already hopeful about it, just for her. And when I saw it — at the Mark Taper Forum, in Los Angeles — elements started arranging themselves in my head. It was a very spare production, and I guess that allowed me to recognize various open possibilities, things that might be layered in. Lois and I had a drink afterwards, and I asked if she could imagine doing a movie of it, because I wanted to work with her. Then she contacted Jordan Harrison. He was receptive, but too busy to write a script himself; he’s been writing for Orange is the New Black for the last three years — but he trusted me and gave us his blessing.

Filmmaker: How did you go about adapting it? Did you mentally take a sledgehammer to it and then build it back up?

Almereyda: It’s a very respectful adaptation, really, with a few sharp alterations to make it a movie, my movie — changes that felt both intuitive and logical. Jordan’s structure is basically the movie’s structure, built out of elliptical leaps in time. No sledgehammer was necessary. I liked his concision, his characters, his dialogue. You have to be paying attention to who’s alive and who’s a hologram of a formerly living person. It’s a story about storytelling and the stories we tell ourselves, stories we hold onto, change, or suppress. In this way, yes, it’s related to Escapes. I changed the setting, brought it to the beach and introduced flashbacks, and weather, and the character of Julie the caretaker became more central — in the play she’s mentioned but not seen. And I added another generational layer: the great-granddaughter who surfaces at the end.

Filmmaker: I was wondering if there’s any similarity with the process of adapting the Shakespeare plays, but that may not make sense.

Almereyda: I would never rewrite Shakespeare. I was tenderly imitating Jordan Harrison — as a writer, I was consciously trying to be in Jordan Harrison mode, but trying to be in Shakespeare mode is idiotic. George Bernard Shaw tried it — he rewrote the last act of Cymbeline, and this was not his most impressive achievement. For me, the challenge in adapting Shakespeare is to winnow things down – the language is so dense, it’s worthwhile to compress and sharpen the text, in places, but I’d never add my own dialogue. In this case, I was slightly more bold.

Filmmaker: You’ve been very clear that it’s not a filmed play, it’s a film, but did you have theatrical rehearsals in terms of blocking and establishing the space?

Almereyda: No, because the movie was shot in 13 days. We had one extra day for exteriors once we’d taken some equipment away from the roof of the house; the actors weren’t around. It’s the nature of this kind of movie that the actors have to be at the ready and invested. You find it as you go, so things are blocked organically, scene by scene. I went in with ideas, but I didn’t insist on anything. I’ve learned how to be flexible, and Sean is good at being fast, and the actors were all charged. They were there because they wanted to be there, and they were equal to the occasion.

Filmmaker: Did you make any attempt to shoot it in order?

Almereyda: Not really, because of actor availability — people were coming and going. It’s actually two houses. We were combining two houses that were almost across the street from each other — one with an ocean view, one without.

Filmmaker: What about the use of The Gates?

Almereyda: Christo’s piece is in the play. It’s a sweet coincidence that Sean trained with the Maysles, and I think he may have worked on editing The Gates, which documents the piece. Jordan Harrison may not have known this movie exists, but it opened a window for me, for this film. Christo also happens to be an important reference point for me, the way he embraces the challenge of bureaucracy and makes art out of it. At any rate, Sean owns Albert Maysles’s Aaton camera, he inherited it, so it’s a nice connection that grew organically. We were lucky to get the rights to The Gates and to My Best Friend’s Wedding – which wasn’t a personal reference for me. I had to admit to Jordan that I hadn’t seen the movie and he said, “Oh, it’s just some silly ’90s comedy, you can put in another one if you want,” but then I looked at it and really liked it. I was glad he chose that one.

Filmmaker: Was there a particular kind of tone or sound that you wanted the house to have?

Almereyda: I’d finished the first draft and then, the next day, saw Ex Machina, and was sort of horrified because there were too many things that were similar. So I worked hard to make this movie distinctly different, and one of the differences was to move it to the beach. I’ve only visited people who live on the beach, but even as a visitor you get seduced by the presence of the water, and particularly the sound of waves, even if you can’t see them. The sound becomes a pulse, an inner clock, infiltrating how you think and feel.

Filmmaker: So what’s the relationship between Marjorie and Escapes for you? Did you sense the affinity immediately?

Almereyda: They both make use of repurposed images, in ways that, I hope, feel surprising and emotional. Apart from that, they’re both movies about storytelling. In Marjorie, Jordan constantly talks about how our identities are defined by the stories we tell about ourselves, and our ability to either hold onto them or lose them. It’s a challenging aspect of being human. If you know someone well, you know a sequence of stories, and even if they’re constructed and adjusted, these stories take on great authority. In Hampton’s case, his ability to tell stories — either writing them down or just talking them through — is one of the central facts of his life. Some of them are adventure stories: he’s probably had more near-death experiences than anyone I know who’s not in the military or a cop, and at the same time he’s a very vital, life-enhancing presence wherever he goes. In my experience, reality bends around Hampton. Things happen to him, and he makes things happen. I don’t know anyone else who determined, at age 15, to run off to Spain and become a flamenco dancer – and did just that. Similarly, he points to a photograph of a young actress and says, “I’m going to marry you,” and then more or less does it. I don’t think he’s given enough credit for Blade Runner, because he didn’t just write the first draft, he recognized the novel’s potential, met with Philip K. Dick, acquired the rights, wrote ten drafts. It’s Ridley Scott’s movie, undeniably, but it wouldn’t exist without Hampton. It’s not like he was some journeyman who got lucky; he really willed it into being. The fact that he has a shared screenwriting credit doesn’t cancel this. It’s is a Hollywood story, with a subtext: screenwriting is a rough trade. I was a Hollywood screenwriter for a few well-paid years, so I know about the odds.

Filmmaker: It felt like some of the clips were from things you wouldn’t be watching of your own accord. Is it fun to slog through all of this stuff?

Almereyda: The fun about so-called “found footage” is it’s like discovering a genie in a bottle: if you release it from its confines in a bad TV show, there can be magic to it. I was happy to keep finding images that I thought were beautiful or mysterious or poignant. I also felt I was submitting to an education in filmmaking, because if you look at early movies by Scorsese and Spielberg, there’s such authority, frame by frame. Every shot has an idea, a narrative intention, a visual signature, and TV, of course, is usually just thrown together. So it was a little bit of a film school to dredge through this terrain, especially old Westerns, at the far edge of my childhood memories. After all, you know, I limited myself mostly to movies that Hampton appeared in or that his friends were in — and Blade Runner, of course. The one exception is Straub/Huillet’s The Death of Empedocles, following from Philip K. Dick’s identification with Empedocles. So that’s a flash of high culture married to Dick’s pulp production. The guy who shot Empedocles, Renato Berta, shot my very first movie, Twister. So again, there are these interconnections, tying in to Philip K. Dick’s theory of how alternate worlds can be interrelated, can penetrate and overwhelm one another. Watching an old movie, you drop into the past and see your own reality from a new angle. Anybody who loves movies can feel some connection to the idea.

Filmmaker: I’m always puzzled by reviews that say your movies are unemotional. The last shot of Experimenter kind of kills me.

Almereyda: I thought that was an emotional movie, because I went at it through Milgram’s marriage. I tried to present a more human and intimate aspect of the man. I didn’t know him – he died in 1984 – but I got to know his wife quite well. As for Marjorie Prime, the play has a lot of heart, and I’d like to think the movie is emotionally aligned with the play. Jordan was writing about his own grandmother, who was in her 90s and had dementia. He was leaning on notebooks that his parents kept while trying to keep her company and explain herself to herself. So it’s inherently emotional territory. I don’t make a study of my reviews, but it’s possible I’ve gotten typecast a little as being brainer than I am. Emotions and intelligence are not disconnected. There’s no reason to separate them and say that they deny one another. So I hope the movies are emotional, and about urgent elements of being alive. At the same time, we all love movies because they have a certain kind of kinetic power that doesn’t have to do with words and ideas. At best, they embody ideas rather than illustrate them. I’ve been grateful when people come up to me and say they were in tears watching Marjorie Prime. I don’t normally hear that about my movies. I won’t reject it.