Back to selection

Back to selection

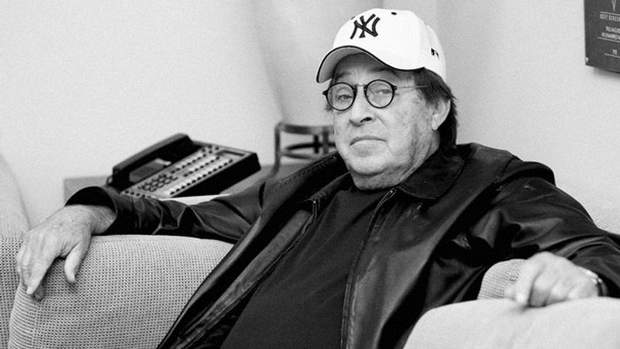

Paul Mazursky Loves Talking To Women

I don’t really know how to describe my conversation with Paul Mazursky. The phone connection was weird, his wife Betsy was trying to control the dog in the background, I was working with this new recording device on my phone and he could hear only every other world I was saying. I was late to watch my kid play soccer so I was rushing and he was so patient but I could tell he was busy too.

But halfway through the call I realized I might be in a Paul Mazursky film where everything happens at once, energy is flying all around and somehow at the end of all the chaos — we are left with something real and true.

And so “the messy” felt right.

I told him why I was calling first. I told him that Concussion had just been put in U.S. Dramatic Competition at Sundance and I owed Nick Dawson an article so we decided it might be nice to talk about what influenced the film. I told him that the character-driven films of the seventies had been my touchpoint and specifically his films that dealt with infidelity; Bob and Carol and Ted and Alice, An Unmarried Woman, Blume in Love, and then a later film I consider his masterpiece, Enemies: A Love Story.

He told me he doesn’t use those words because he’s been around a lot of “masterpieces” in his life. I kibitzed and told him it wasn’t up to him to decide what my masterpieces were and why. And he said, fair enough.

I’ll let him speak now — it’s way more interesting.

Filmmaker: Infidelity is a theme in your work which drew me to many of your films when I was writing. I watched An Unmarried Woman several times in particular. You draw women very well.

Mazursky: Well, first of all, without getting into any kind of pretenses, I always felt that women were easier to talk to than men, ’cause men are always talking to you about baseball — which I love — but men are always talking to you about baseball and who got laid, but it’s not real. Whereas women are more open and more emotional in my experience. My mother was bipolar and sometimes she would have her up days and sometimes her bad days. She would always take me to arthouse films and I loved her. So I’ve always felt very close to women. I have been married for over 60 years, and 28 of those years were just wonderful….

[I laugh for a very long time. And he starts in again.]

I got the idea for An Unmarried Women from a friend of Betsy’s — and I liked her very much too — who was divorced.

[His dog barks.]

Get the dog quiet, Betsy! Jesus. So one day she bought a house and she showed us the deed to the house and on it it said her name and next to it it said “An Unmarried Woman.” And I had never heard of a house being bought by just a man saying “an unmarried man.” So I got the idea about a divorced woman, and I started interviewing women who were unhappily married or no longer married about what it was like, and I heard some great stuff.

Filmmaker: You get consistently amazing performances from actors, and you are an actor yourself, but how do you work with the actor to capture those moments? I think of Robin Williams saying goodbye with his arms flapping, crying in Moscow on the Hudson. I think, “How the heck does he do that?”

Mazursky: My advice is I don’t give advice. I studied the Method. I don’t want them to anticipate. I just want them to think about a day in the life. And do it. I do a lot of emotional reacting. I can’t help it. When they make me cry, I cry. When they make me laugh, I laugh. I get angry, I’ve gotten angry. My advice is to not tell the actors too much, let them tell you as much as they can.

Filmmaker: How did you get Lena Olin to growl like that in Enemies: A Love Story?

Mazursky: Oh god, right? She was great. She was a great actor. She would not use a stand in. She stood in for herself. I don’t know, I guess I got lucky with a lot of stuff.

Filmmaker: Who was your favorite?

Mazursky: I think one of the best actors I ever worked with was Art Carney, who won the Oscar for Harry and Tonto. I never told him anything. Nick Nolte, for Down and Out and Beverly Hills, he’s a great actor. George Segal was great; I used to call him my Jew. I had two great Jewish guys that played my Jews — Georgy and Richard Dreyfus, both complicated guys. All the actors I worked with underneath it, were me, some form of Jew.

Filmmaker: How do you keep it as charged in your films, always packed full of funny, sexy, sad moments?

Mazursky: Fellini was a good friend of mine. Fellini got the the closest to it. When you’re doing things all at the same time in the movie, when you’re laughing, you’re happy, you’re amused, you don’t like anything and suddenly… you find yourself very moved.

That’s what Chekhov does. He has five people talking about different things at the same time. “I want to go to Moscow; we’re going to Moscow,” “I had a stomach ache this morning.” “Do you eat corn flakes?” “Have you every been to Siberia?” “Have you ever read this book?” Suddenly somebody farts. And at the end you hear a shot ring out and someone has killed himself. And you hear the wind. Life going on.

The more real it is, the better it is. It’s everything at once.