Back to selection

Back to selection

On Finding New Screenplay Structures for Independent Films

Fargo

Fargo The below is a guest essay by Jennine Lanouette, Founder and Chief Content Creator at Screentakes Digital Publishing, who is currently in the midst of a Kickstarter campaign for a line of media rich screenplay analysis ebooks. Lanouette has taught screenwriting and lectured on story structure and script analysis for over 20 years, and much of her wisdom can be found at her site. The new ebooks use text, video and interactive graphics to provide a new dimension to screenplay study. For more details, and to donate to the campign, visit its Kickstarter page. — SM

It often seems to me that the independent film community is not entirely comfortable talking about screenwriting. Or perhaps more specifically story structure. This is not surprising considering a Hollywood Screenwriting Advice Industry has grown up over the past 20 years pushing a mono-minded model of story structure that a creative innovator could find stifling.

The truth is that the Hero’s Journey, Save the Cat, Syd Field Paradigm, or whatever is the structure template du jour, are all just variations on what any decent Screenwriting Fundamentals class would teach about our historically derived model of drama, generically referred to as Three-Act Structure. But the Screenwriting Industrial Complex does not deliver it to us as simply a beginning point that a creative person can noodle around with and push in new directions. Rather, the screenwriting advice givers drive home the message: “Stray from this model at your (commercial) peril!”

Independent film, however, exists, by definition, for the very purpose of straying from conventional models. This may explain the collective covering of the ears to shut out all that story structure noise. As a longtime teacher of screenwriting always looking to engage with others on this topic, I have to cover my ears sometimes, too. But something is lost when the only alternative to the noise is to avoid the issue altogether.

There’s no avoiding Three-Act Structure. It is the One-Point Perspective of screenwriting. Just as in drawing, you have two points on a horizon line and then a third vanishing point to create a sense of space, in filmed drama, you have a beginning, middle and end to orient the viewer in time.

However, within that three-part structure, there are infinite possibilities for what can be achieved. This is the Advanced Screenwriting class, where a healthy respect for the model handed down to us by centuries of dramatic innovators is combined with an acknowledgement that artistic evolution depends on continually seeking new ways to apply the old models. Hollywood used to be open to cultivating, or perhaps simply tolerating, such ambitious endeavors. But, considering that today’s Hollywood has sunk into a comic-book-franchise/based-on-a-true-story rut at the expense of original adult drama, I would like to suggest that the evolution of the art form is now the sole responsibility of independent filmmakers.

Indeed, there have been some beautiful examples of screenwriting innovation recently: the Coen brothers’ Inside Llewyn Davis and J.C. Chandor’s All Is Lost are two of my favorites (which I’ve written about on my website). Ironically, it was just as the Screenwriting Advice Industry was taking hold 20 years ago that Quentin Tarantino provided indie counter programming when he turned three-act structure on its head in Pulp Fiction (which I’ve often analyzed in my lecture classes). Using basic story structure principles, he created a structural system all his own. This is at the core of getting beyond the mono-minded model.

After years of studying story structure, here’s what I have concluded: It actually doesn’t matter which structural model you use as long as you have some kind of underlying structural system to your drama. You start with Three Act Structure and go from there. When you apply your structural system consistently throughout your story, the viewer will unconsciously derive security in knowing there is an underlying structure at work. All the different shapes and sizes these structures take is where the interesting conversation lies in screenwriting for indie film.

But how to frame that conversation? How to expand on the Three-Act Structure model without simply reiterating differently articulated versions of the same thing? One way is to get beyond the excessive focus on plot that we see in the conventional model and give more consideration to how character and theme can function in determining a story’s structure.

My definition of a story is that you have to go from A to B, which is to say you have to give the viewer the sense that they have ended up somewhere different from where they started. How this works in a plot-based story is fairly evident: the solving of a problem, the triumph over an enemy, or the unraveling of a mystery all reflect an A-to-B progression from beginning to end. This is what the conventional model concerns itself with.

Along with that plot story, however, there can also be a character A-to-B progression, in which we see a significant internal shift in the main character from, say, timidity to courage, or insensitivity to tenderness, or any one of hundreds of ways in which people evolve in response to life’s external challenges. When an A-to-B character progression is fully pronounced, it can exist in a structure as a distinct story line operating in tandem with the plot story line. Looking at structure this way, you already have a potentially more layered and complex story in front of you.

But, for me, story structure starts to get really interesting when you find that there is also a theme with its own A-to-B progression. The place at which we arrive at the end of the theme story is a new understanding of human nature, society or the world. To find this progression in a film, you want to ask the questions, “What is the nature of the world we are in at the beginning of the story?” and, “What is the nature of this world at the end?”

I like to cite Fargo as an example. It begins in a world in which a Hardy Boys style kidnapping caper seems harmless enough to pull off with no one getting hurt and gradually progresses to a world of insatiable greed, psychopathic murder and gratuitous dismemberment. When it came out in 1996, Fargo’s contained world presented an apt metaphor for what had become of our society overall, and, therefore, resonated with critics and viewers alike. So, in the thematic A to B progression is where we can find the metaphoric meaning of the story.

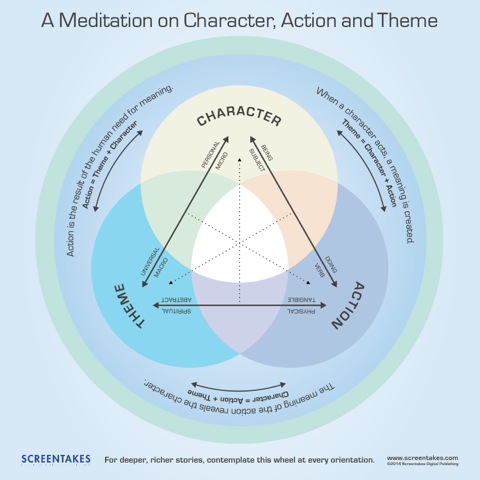

These character, action and theme story lines can exist all together or in different combinations and with different degrees of prominence. I created the infographic below as a way to describe a lack of hierarchy among them. Character is not simply decoration on the plot with theme floating around abstractly somewhere above. Rather, each exists as its own entity in balance with the other two. Plus, they are interrelated, with any two forming certain dichotomies while together having a distinct relationship to the third.

I have presented them in a circle to indicate that any one of the three can be placed at the top. In other words, you can start with a character story and build in action and theme layers to support that character journey, or start with a theme story and cultivate the action and character elements that will embody those ideas, or, what we see most often, start with plot and add on the character and theme stories to provide more depth. (I have also created digital and hard copy versions of this infographic in which the wheel actually turns to give six different orientations.)

I don’t mean to suggest, however, that this building of layers needs to happen through a conscious thinking process. Conscious thought has its place in tweaking and refining. But, most often, the deeper elements of a story come from an unconscious, intuitive place of pure imagination, sometimes to the point where not even the writer is entirely conscious of all the layers in their script. This is why it is somewhat counter-productive to attempt a proscriptive “how to” for creating stories that are character-rich and deeply thematic (and, thus, why the popular screenwriting methods stick to just talking about plot).

Nonetheless, I believe it is possible to cultivate and educate that part of your creative unconscious. The first step is opening your mind to the possibility of other paradigms than what you accept as given. I open myself to finding a new paradigm each time I study a new film for my Script Analysis class. That paradigm then becomes embedded in my unconscious and informs my understanding of other films. Two films I’ve lectured on that have taught me much about the integration of distinct plot, character and theme story lines, and, thus, are excellent illustrations of what I’m describing here, are The African Queen and Thelma & Louise. Currently, I am converting those lectures into media-rich ebooks with video and interactive graphics (which I am offering as rewards, along with the digital and hardcopy versions of the wheel chart, for the Kickstarter campaign that will help me finish making them).

But my purpose in creating this wheel chart, which I have titled “A Meditation on Character, Action and Theme,” is to offer another method for integrating a new paradigm into your unconscious. Study it, stare at it, enter into a deep contemplation on it and see what new thoughts and ideas it stimulates for you. Then, the next time you sit down to work on your own script, or read another’s script, or simply go see a movie, see if you might look at that story a little bit differently. You might see more layers in it than you would have before, or you might sorely miss the lack of them. Let me know what you experience. I’d love to hear it. I’m hoping this infographic will help us start talking about Indie Screenwriting.

Jennine Lanouette has taught screenwriting at Lucasfilm, Pixar, Film Arts Foundation, The New School and the School of Visual Arts, among others. Her website, Screentakes.com, offers in-depth studies on story structure for film professionals. She studied screenwriting at Columbia University and the history of drama at New York University. Currently, she is making multimedia ebooks of her Script Analysis lectures.