Back to selection

Back to selection

PAIRING FILMS AT IDFA

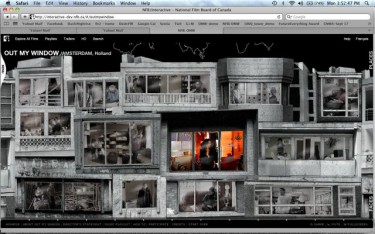

For a docu-phile, attending the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam — with its nearly 300 films to choose from — feels less like being a kid in a candy store and more like being stuck in Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory for a week and a half. In addition to being Europe’s biggest fest for nonfiction flicks IDFA boasts round the clock events. (Literally — if you were still revved at three in the morning after IDFA Dance Night a program called “Docs Around The Clock” continued until 9AM, breakfast included.) In between screenings at the Pathe de Munt or the gorgeous Pathe Tuschinski, named for the movie-loving Polish immigrant who built the stunning Art Deco cathedral before perishing in the Holocaust, there was enough to keep even the most ADD-addled attendee busy. You could go to debates and panels in the afternoons, and “Guests meet Guests” meet-and-greets at Brasserie Schiller followed by talk shows and a free surprise film screening at the Escape Club in the evenings. There was also an art exhibition titled “Expanding Documentary” that starred the dynamite “HIGHRISE/Out My Window” (pictured above), an installation featuring an international array of 360-degree images from Webby Award recipient Katerina Cizek. And I haven’t even mentioned the brunches, dinners and after-parties (nor the master classes or various markets if you came with a doc to pitch).

Needless to say, shaping an article out of this much cinematic material begins to feel a lot like making a documentary itself. So after sitting through hours and hours of footage trying to craft a cohesive whole (and concluding that the world series of filmmaking belongs to Romania and Denmark), I’ve decided to take what I’ll call the helpful, Netflix “If you like this, you’ll love that” approach and apply it to a list of buzz films and their below-the-radar equivalents.

Will Play in Peoria? Davis Guggenheim’s indictment of America’s public education system Waiting for Superman is a thousand times more personal and heartfelt than his An Inconvenient Truth, and the harrowing sequence in which the mostly inner-city kids he’s been following finally face Judgment Day in the form of a lottery drawing sealed the film’s Oscar nod. But Tyler Measom and Jennilyn Merten’s Sons of Perdition (which I happily discovered at Tribeca after walking out of a screening of the tedious Feathered Cocaine, also inexplicably selected for IDFA), ups the youth-in-peril stakes tenfold. Acquired by the Oprah Winfrey Network this year the doc is an emotional rollercoaster ride deep inside the lives of three rural, blue-collar teens recently escaped from their fundamentalist Mormon community. While the heartbreak in Waiting for Superman comes from watching loving families tethered to a broken system, the uneducated protagonists of Sons of Perdition are destined to be forever cut off from their kin.

Bona Fide Art-house. No surprise that consummate craftsman Frederick Wiseman’s hypnotic peek inside a mom-and-pop Boxing Gym in Texas was one of the darlings of IDFA’s “Reflecting Images: Masters” program, which also featured Allentsteig, the latest from Nikolaus Geyrhalter, who rendered industrial food processing riveting in Our Daily Bread. Geyrhalter is at it again, this time revealing the inner workings of a military training ground originally set up by the Nazis that also happens to hold a nature preserve. The odd and often humorous juxtaposition between soldiers and wildlife, not to mention the rural townsfolk whose homes are occasionally the targets of collateral damage, makes for a filling philosophical stew.

Asian Displacement. Lixin Fan’s Sundance 2010 hit Last Train Home is a small and tender portrait of the largest human migration in the world, when factory workers annually return to their villages during Chinese New Year to children they often barely recognize. But also in the IDFA mix this year was Jia Zhang-Ke, who brings the same effects-of-globalization theme and fiction artistry of The World to doc form with I Wish I Knew. While elderly men and women recount their daily lives in Shanghai at the advent of the Cultural Revolution the director subtly represents these tales through brief reenactments, well-placed ambient sounds, and montages of modern-day street images, and period photos and footage. (Plus, for the hardcore film buffs the doc includes interviews with Hou Hsiao-Hsien and with several leading ladies from the era.) The result is as if Wong Kar-Wai met Wim Wenders in a waking dream.

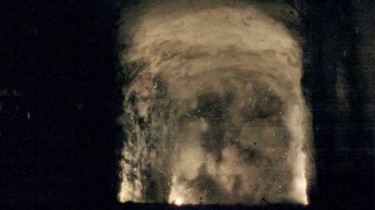

Danish Environmentalism. Ondi Timoner is one of those slick, hipster-friendly filmmakers I grudgingly admire. Her latest, Cool It, a fast-moving global trek with the Danish “skeptical environmentalist” Bjorn Lomborg to uncover alternative solutions to the current climate change policy, may have Moby on the soundtrack but it also manages to make the arcane visual. (Too bad Timoner wasn’t one of the directors on another IDFA doc, the uneven omnibus Freakonomics.) But the film that rightly nabbed IDFA’s inaugural Award for Best Green Screen Documentary, Danish director Michael Madsen’s Into Eternity, goes beyond a simple cinematic exploration of Finland’s nuclear waste storage facility, Onkalo. Madsen instead has crafted a cold, existential nonfiction film that plays like a Halloween horror flick. With his aptly titled doc he leads us on a creepy, jaw-dropping journey that resembles nothing less than Lord of the Rings meets 2001: A Space Odyssey. HAL meet Onkalo.

Damsels in Distress. Tabloid is classic, practically retro — its leading lady would have felt right at home in Gates of Heaven — Errol Morris. Taking as his jumping off point the real-life tall tale of what the British press dubbed the case of the “manacled Mormon,” Morris meticulously tries to piece together the truth about one Joyce McKinney, a still bubbly and vivacious ex-model who decades ago was accused of kidnapping and raping the religious object of her obsession. It’s a delightfully wild romp that leaves one wondering why Herzog hadn’t made this material into a feature years ago. But the Danish mother-daughter duo at the center of Eva Mulvad’s The Good Life is every bit as riveting as Ms. McKinney. Mulvad’s riches-to-rags film has been compared to the great Grey Gardens, but that’s a bit misleading since both the eccentric fifty-something daughter and her octogenarian mother are undeniably sane. “The newly rich are doing well but we old rich are the new poor,” the daughter laments now that they’ve spent all their wealth and reside in Portugal on her mother’s meager pension. (“I’d rather die than work,” she explains.) But at its heart The Good Life is a respectful portrait that addresses universal issues of growing up and having to face mortality, of losing everything and having to start over. The surprisingly hilarious, too-good-to-be-true dialogue and breathtaking shots of the Portuguese seaside are simply there to soften the blow.

In The Mood For Lust. Alex Gibney’s Client 9: The Rise and Fall of Eliot Spitzer smartly doesn’t dwell on the salacious and overly reported aspects of the former governor of New York’s downfall following his public outing as a high-end escort john. Instead, Gibney trains his lens on the much more alluring he said/he said between Spitzer and the titans of Wall Street he’d gone after during his Attorney General days, all of whom had been waiting for the chance to push the button at the demolition of his career. While steamroller Spitzer may have sacrificed higher office for sexual fantasy, the subjects of British director Julie Moggan’s lighthearted and poignant Guilty Pleasures are fully able to separate their realities from a Harlequin novel — one of which gets sold somewhere in the world every four seconds, as we’re told at the beginning of Moggan’s doc. The film follows three female romance readers (a married office worker from England, a Japanese housewife and an Indian woman separated from her husband); a balding British gent who happens to be one of Harlequin’s most prolific writers; and the muscle hunk that’s graced around 200 covers. But what’s most titillating is how Moggan takes her time setting up the clichés only to then meticulously tear down our preconceived notions of these “types” one by one. In the process, she reveals that a loving reality can be better than an unattainable fantasy. Something I’m sure the former governor would now agree with.

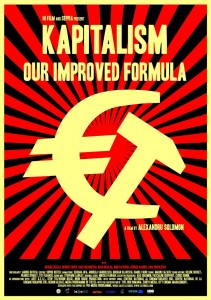

Economics Gone Wild. Much like interview subject Eliot Spitzer once did, Charles Ferguson, the levelheaded director of Inside Job, boldly takes on the people and policies that led to the global economic meltdown of 2008. Then he goes one step further to explore the culture that allowed government and corporate corruption to grow and thrive in the first place. The conclusions reached are terrifying. Indeed, Ponzi schemer Bernie Madoff’s crimes (the subject of another IDFA doc, Jeff Prosserman’s pointless The Foxhounds) pale in comparison to the shenanigans going on in Washington and on Wall Street. Today America’s wealth inequality is higher than in any developed nation — and our banks are now bigger, more powerful and more concentrated than even before the economic collapse! Something a nation like Romania — which has the smallest GDP of any former communist country and the most millionaires — can surely relate to. In Kapitalism: Our Improved Formula, director Alexandru Solomon interviews Romania’s version of Russia’s oligarchs, refreshingly forthcoming men (most with former ties to the Securitate), to uncover an economic system that seems to have adopted the worst of both ideological worlds. Nikolai Ceausescu, Solomon assures us, would have been proud.

The Untouchables. Kim Longinotto’s Pink Saris follows the unconventional feminist founder of the “pink gang” who fights for lower caste female rights in India. The loudmouthed and aggressive Sampat, whose chosen modus operandi is bullying, is the outrageous opposite of what women are supposed to be in a patriarchal society that demands absolute submission and obedience from the fairer sex. Her hyperbole — “I’m the Messiah for women,” she threatens one guy — is matched only by her cult-like charisma. Indeed, perhaps the most disquieting scene in Pink Saris occurs when Longinotto lets her camera linger on a girl who’s been saved by the media savvy Sampat after a broken engagement. As the leader approvingly looks on the budding teen speaks of her newfound activism in the tone of someone reciting from a script. You suddenly realize that for this girl “freedom” is nothing more than simply trading obedience to the malignant men in her life for submission to the benign pink saris. Sampat’s method of deprogramming is simultaneously its own form of indoctrination. On the other hand, Seong-Gyou Lee’s My Barefoot Friend approaches the subject of India’s impoverished class, referred to as “untouchables,” from the male POV, following a rickshaw driver in Calcutta for a period of ten years. Indeed, simply knowing how much time the filmmaker spent with Shalim and his colleagues puts a different gloss on the startling opening sequence in which the family man at wit’s end rages at the director to stop shooting him and to just get out of his life. Where does a filmmaker draw the line once he’s developed a relationship with his subject? Is the director being exploitative by refusing to stop shooting? Or is Shalim, by ordering that filming cease, trying to change the rules and now direct the movie himself? Who’s manipulating whom? That the director is brave enough to pose these questions without pretending to have the answers allows for a noble activist doc to emerge.

But is it Trash? Lucy Walker’s Waste Land is another film that directly addresses an artist’s obligation to his subjects. Walker’s own subject, the artist and photographer Vik Muniz, returns to his native Brazil to engage the local workers at the world’s biggest landfill in his latest project to create art out of the very same recyclable materials they pick for a living. But Muniz hadn’t counted on changing lives to the extent that many couldn’t face returning to their former meager existence once he and his crew had left town. The artist at the center of Alexander Nanau’s respectful and poetic The World According to Ion B., however, has the opposite problem. “From the dumpster straight to the gallery!” a headline in a newspaper announces upon the debut exhibition of Ion Barladeanu, who just a couple years ago was a homeless alcoholic. Now his innovative and surprising pop art collages are shown alongside Warhol (who he’d never heard of, pop art having been suppressed as degenerate under Romania’s dictatorship. One art critic writes that if Ion’s anti-regime collages had circulated during the communist days he certainly would have been a wanted man.) By digging right through the hype Nanau’s doc (backed by HBO Romania) exposes a socio-politically aware artist who feels safer anonymously sleeping on the streets with a bottle of liquor — the only means of keeping the psychological fallout from Ceausescu’s reign of terror at bay.

It Seemed Like A Good Idea at The Time. Alas, Abel Ferrara is at it again — or rather all over the place again a la Chelsea on the Rocks — this time in Naples. In his latest doc, Napoli Napoli Napoli, he films female drug dealers, men’s prison reenactments, a youth center that includes programs for both addicts and artists, and a heavy-handed, staged storyline involving young mobsters preparing for a hit. Snort, shake and repeat. Also to be missed is Jeff Prosserman’s The Foxhounds, about a crew of white-collar finance dudes led by Harry Markopolos, the whistleblower who originally alerted the SEC to Bernie Madoff’s criminal mischief. Fancying himself James Bond with a knack for numbers Markopolos hams it up for Prosserman (who himself seems to have watched fellow IDFA director Errol Morris’s Thin Blue Line one too many times), including gamely staging reenactments of scenes that happened only in Markopolos’s own head. (Nope, his car never blew up when he turned the key in the ignition, regardless of the sound of an explosion heard off camera.) “I was like the boy who cried wolf — except there really was a wolf,” concludes the man who tried to bring down Madoff. Except he didn’t. Unfortunately, “I told you so” is not a compelling storyline.