Back to selection

Back to selection

Prometheus Screenwriter Jon Spaihts

Telling the origin story of the creature that terrified us in Alien over three decades ago, Ridley Scott’s Prometheus is one of this summer’s most hotly anticipated films. But somewhat surprisingly, the origins of the screenplay came as much from a screenwriter’s general meeting as the story material developed for that original movie. At a meeting in the offices of Scott’s production company, Scott Free, screenwriter Jon Spaihts was asked to riff on the possibilities of a film that would revisit the Alien universe. What resulted is Prometheus, with a script credited to Spaihts and Damon Lindelof. Below I ask Spaihts to tell us his own origin story — his background, how he became a professional screenwriter, about his Black List hit Passengers, and his thoughts on working in today’s Hollywood.

Filmmaker: When did you start writing screenplays? How young were you, and how did you decide that was what you wanted to do?

Spaihts: I’d wanted to write stories for a living since I was a child, and for most of my life I expected to become a novelist. But in my twenties after college I had a production company in New York City with an old college friend, and we did documentary video, largely for museums and interactive media. For the first time I held a camera, edited video, scripted, directed and shot; I learned the vocabulary of film. Almost instantly, all my writing aspirations translated from prose to screenwriting.

Filmmaker: Tell me a little bit more about your work with this production company. What kind of video did you do?

Spaihts: We did a big contract for the Museum of Natural History in New York City on a project called Gist2, which is an ice-core project. They drill into the Greenland ice sheet, and they can tell very detailed things dating back to 250,000 years about Earth’s atmosphere — detecting signals from forest fires, meteorite impacts, and even stray atoms of lead from Roman lead smelting 3,000 years ago. It’s an incredible record of the atmosphere.

Filmmaker: Did you start the company having a base of knowledge in the art or science worlds? Or did you just look for clients who would respond to your video skills?

Spaihts: Well I had been a freelance writer up until then, including some museum work, and my college friend who was my business partner had been a video producer and had done a lot of commercial work. So I brought the expository and explanatory skills to the table, he brought the video vocabulary and between the two of us we set to making this media. We did some work with the Natural History Museum, including covering the case against James Earl Ray, the assassin of Martin Luther King Jr. One of the things I had to do for that job was go down into the archives of the Memphis Courthouse, put on white gloves, and handle and photograph all of the evidence against James Earl Ray, which included the rifle that fired the fatal shot, the bullet broken into three fragments that was removed from the body of Dr. King, and a lot of creepy paraphernalia that had belonged to James Earl Ray when he was apprehended, including cans of beer and boxer shorts and his hair brush. It was dark and disturbing and in some ways the closest thing, handling this bullet, that I have ever come to a religious experience. It was probably the most powerful physical object I have ever touched.

Filmmaker: Were you trying to write novels during this time?

Spaihts: I was writing. I always had an active notebook and kept a file of stories and was breaking them out into detailed outlines, elaborating scenes and particular bits of business. But I can’t say I was writing chapters of novels; I was working too hard. That was always the way in which I shot myself in the foot — I never had an undemanding day job around which I could write. I was always working long hours and taking my work home with me. I was a terrible aspiring writer in that way.

Filmmaker: The first thing I know about your bio is The Black List and Passengers, but there must be something between what we’re talking about right now and that.

Spaihts: The media and production company I had with a friend of mine was acquired by a dot-com, an education technology company called Teachscape. so we went off to be dot-com executives and devoted our skills to that company. I was a dot-com executive for five years, and that was exciting and challenging and intellectually demanding and rigorous and lucrative, and in all those ways a terribly dangerous job because it was just satisfying enough and lucrative enough, and it led me down a path towards becoming a technology company CEO at some point. I could see myself getting stuck in it. I knew that if that happened, to the end of my days I would look back and wonder what would have happened if I had really pursued writing and chased that dream. I would have been wistful until I was old and grey, and I didn’t want that to happen to me. So while I was being a dot-com executive I saved my money into as a big a pile as I could and finally quit my job and spent a year writing. I wrote this one big screenplay called Shadow 19. I taught myself the screenplay format on that script, and I rewrote it 27 times until I thought it was kind-of bulletproof. Finally I started showing it to people. I networked a little bit, I got lucky and in very short order I met my current manager, Lawrence Mattis, over at Circle of Confusion. He loved the script, met with me and decided he wanted to represent both me and the screenplay. Before I even had agents he sold it to Warner Brothers, and I moved to Los Angeles to make a go of it.

Filmmaker: When you were networking that script, who did you get it out to? People you knew from the dot-com world, or were you able to make industry connections?

Spaihts: While I was at the dot-com I worked briefly with a guy named Richard Brick, who was Woody Allen’s line producer. He was film commissioner of New York for a while, and he came in and did some consulting with this company and we became friends. Even after he and I had both moved on, we would meet occasionally for a drink and catch up because we liked each other. He was my solitary contact in the film industry, and when I finally felt I had a screenplay worth showing I sent it to him and he loved it. It was a short chain of handshakes from there to Lawrence Mattis.

Filmmaker: What was that script about?

Spaihts: It is a hard science-fiction action epic about an elite soldier in the far future who is sent on a suicide mission to a hellish planet again and again until he gets it right.

Filmmaker: Tell me a little about your interest in science fiction. Was that an interest growing up when you were a kid or something that developed once you decided to write for Hollywood?

Spaihts: When I was very young my reading tastes were exclusively fantastic. I read fantasy and science fiction as voraciously as possible and absorbed an enormous amount of source material that way. By the time I got to college my tastes had pivoted and I was more interested in literary fiction and that was what I was expecting to write. But I still had these mountains of science-fiction stories that I ingested in my formative years, and when it came time to think about what I wanted to write for film, I was thought of the films I loved back then, and a lot of them are these seminal science-fiction classics.

Filmmaker: Which ones?

Spaihts: I love early sci-fi films like The Day The Earth Stood Still and Forbidden Planet, I was completely drawn in by 2001, the first two Alien films, the first two Terminator films. There is so much extraordinary science fiction in film, when I went through my notebooks looking for filmic notions and trying to figure out what to write first I had all manner of things, from highly conceptual character-driven stories to period pieces set 1,000 years ago to far-future sci-fi epics. And I guess I just chose the notion that seemed most compelling and most unique, and that was Shadow 19. That also placed on the Black List, though less auspiciously.

Filmmaker: Who were some of the literary fiction authors you were reading after your science-fiction period?

Spaihts: I had an intense Robertson Davies period, I think Norman Rush’s Mating is as good a book as has been ever written. I adored Joseph Heller, had a big period diving backward into classic pulp stories, Raymond Chandler… I read everything — Ralph Ellison, Zora Neal Hurston, and the Harlem Renaissance was also really important.

Filmmaker: Your writing process today, is it very much different now than it is when you started writing scripts?

Spaihts: I don’t think it’s ever modulated that much. I’ve always been an outliner. I start with concept. Well I can’t say that — sometimes I’ll start with concept, sometimes with characters, sometimes with a seminal image. It varies from project to project, where the first seed is, but in general if you begin with character that character’s nature or fate will call a conflict out of the ether and that will be the right kind of conflict for that character. And if you start with a predicament it will invoke generally the sort of protagonist you want to invoke in that sort of predicament. Basically, the one thing calls the other. Whatever the seed is, it tends to make the others feel necessary.

Filmmaker: How about just the physical process? Are you someone who writes four hours a day? Eight hours? One hour?

Spaihts: I wish I had a tidy answer to that question, I’m still a mess. I know people who work bankers’ hours, who write like clockwork and turn off the internet and exist in what sounds to me like a Neverland of perfect discipline. I am not there yet. I want to be, but I am honestly still trying to find the form of work that works for me reliably. There are things I have written mostly at night, and there are things I have written around the clock driven by white-hot deadlines. There have been things I have managed to get done in bankers’ hours every day, working steadily and comfortably and seeing friends in the evening. There is no consistency to it yet for me, I am still looking for the durable form. Maybe the durable form is an illusion, maybe it’s like this for all writers. Some projects come easy and some you have to drag out of yourself like lifeblood. I don’t know. All I know is that for me that it’s never been the same way twice.

Filmmaker: So what happened after Shadow 19? Was Passengers the next script after that?

Filmmaker: So what happened after Shadow 19? Was Passengers the next script after that?

Spaihts: It was. Keanu Reeves was attached to Shadow 19 when I was developing it at Warner Brothers, and he and I came to a version of the script we both loved and wanted to get made. And we couldn’t convince the studio to make it. The studio moved on and hired other writers and the project took off in a direction we didn’t like. So we both went on about our business and a month or two later I get a call from Keanu’s people saying, “Hey, he wants to find something else to work on with you, let’s pick a project.” So we met, and I threw a few of my ideas at him. One of them was a hardboiled noir cop story set in the present day that took a big sci-fi hook at the end. He was intrigued by it, and we talked about it for maybe six weeks. It was a very bleak dark story and in the end he said, “This is too dark for me.” But it featured prominently the image of a man stranded alone in space. He couldn’t let go of that image, and his business partner called me and said said, “Look your story is not for us, but we love this image. Is there a happier story that can be told?” It was a powerful question. I had never asked it of myself but it was one of those moments where a story seemed to leap from my head fully formed and one idea seemed to lead to the next with a beautiful necessity. In about half an hour I riffed the spine of the story that became Passengers. They hired me to write it, I wrote it, and we are still working hard on getting it mad. Things are not looking bad these days though I can’t say very much about how it is going.

Filmmaker: At this point, you’re living in L.A.and pretty much set as a working screenwriter. What happened after that?

Spaihts: I wouldn’t say I was set. I was certainly becoming known. I took a great many meetings and was talking about a lot of things. There was a funny happenstance where Passengers was released into the world not long before the writers strike. The writers strike happened and no new material hits town for month. During that period, Passengers passed from hand to hand and spread across Hollywood, was very widely read and it was acquired a big fan base. It might have done so anyway, but I think it benefitted from the absence of competition for a few months time. It travelled laterally from friend to friend just based on recommendation to such an extent that, even now, with Prometheus coming in for a release, if I walk into a meeting people are just as likely to talk about Passengers as anything else. In the small town of Hollywood it’s kind of what I’m famous for.

Filmmaker: What are your thoughts on maintaining your focus or your sanity after you have that kind of initial interest but you haven’t made a film yet? I know many writers who seem to get stuck in an endless cycle of development meetings.

Spaihts: Well people take many roads into the industry, and I hesitate to pontificate because all I know is how I came in. I don’t think I know a right answer. There are people who come in, get a studio job right off the bat, are well paid for it, are launched, and never have a hard season. I have had a hard season. I took meetings for more than a year, and everyone was incredibly complimentary, everyone was flattering, engaged, keen to work with me, eager to be in the Jon Spaihts business, and then I went more than a year without getting a job. And that’s an adjustment, because every fresh writer coming to town off a spec sale or an option and starting to do the meeting circuit thinks that every meeting is a job interview that might turn into that wonder gig. In fact, most of those meetings are merely introductions. They’re just people getting to know you — seeing what you’re like and what it’s like to talk to you. Most of them were never going to be jobs, even on their best day. You have to adjust yourself to that notion and realize that you’re building a constituency; you’re meeting everyone, you’re learning what it’s like to talk to these people, and they’re learning what it’s like to talk to you. If things go well, you’re building a fan base. I actually think it’s a very important point in your career. But it’s a lean time, when you’re doing more talking about work than actually working. It’s a kind of coming out. Most of the writers I know have been through it. In a very real way, when I did start getting jobs, to some extent I owed them to whatever pitch I made in the room that day, to my take on the story, and then to some extent to the reputation I accumulated just by chatting with people.

Filmmaker: This may be an impossible question, but what do you think people thought of you when you came in? What are you like in the room?

Spaihts: I don’t know, because I don’t know what other writes are like in the room. I can only make guesses based on what people have said about me. From what I gather, I seem well-read and the stories I write seem “novelistic.” That’s a word I keep running into. I write “novelistically,” apparently. So I suppose that tells me something about what I’m up to which I suppose is that I’m a nerd and that I write complex stories.

Filmmaker: What was between Passengers and Prometheus?

Spaihts: I rewrote a film called The Darkest Hour for New Regency, that was subsequently rewritten by its director and a couple of punch-up guys. I wrote an original called Children of Mars, for Scott Rudin, a story that I still love and hope to see made. I wrote a version of George and the Dragon for Doug Wick, producer of Gladiator. And I think that’s all I got done for studios before Prometheus came along.

Filmmaker: So how did you get Prometheus?

Spaihts: I went to a general meeting with Scott Free. They just wanted to meet me on the basis of things I’d written that they had read. As is often the case in general meetings we shot the breeze about a lot of different possibilities. They owned the rights to certain books, they wanted to rewrite certain movies. They wanted to know if I had original ideas. Late in the meeting, they said that Ridley had been thinking for a long time about returning to the Alien universe. Since no one could see how to continue the existing franchise forward it would have to be a prequel, something set before the time of the first film, and they asked whether I had any ideas. I hadn’t been asked to prepare anything for the meeting or really thought about it before but I found that I had a lot of ideas. I talked for maybe 45 minutes and when I was done I had outlined a story, main characters, set pieces, a mythology and sort of fleshed it out in the room. The guy I was talking to, the head of Ridley’s company, asked if I would write the idea down so Ridley could take a look because he was still in post production on Robin Hood at that time. You’re not supposed to write down your stories and leave them behind as a screenwriter if you’re not being paid, but it was Ridley Scott so of course I did. Something like ten days later, maybe two weeks, I was sitting in a room with Ridley Scott and the co-chairs of 20th Century Fox, and we were doing a deal. From there I was outlining and then writing the script, and I worked through five drafts of the screenplay with Ridley Scott over a number of months.

Filmmaker: What do you think accounted for your ability to do that on the spot? It is because you area a huge fan of the Alien films and remember their world so well? I’m a big fan of those films too, but to be honest it’s been a long time since I saw them and I don’t think I’d be able to jump into that universe at a moments notice.

Spaihts: I think, yes, Alien and to a slightly lesser extent Aliens, have lingered in my memory, and so I did have some facility about the universe. But I also think some of it was pure blind chance. I don’t think I have some magical power to whip out a fully-fledged screenplay idea at the drop of hat every time I’m asked a question. This was just a question that hit me at a crossroads of my own fascinations. It was the right question to ask me. I’ve been asked the wrong question hundreds of times in interviews. I really don’t mean to claim some superpower — it was just a question that landed near a lot of things I love. So I was able to make connections between them and find my way into a story and mythology I found really compelling. It worked for me because I got excited.

Filmmaker: What were some of those things? You talked a little bit about Passengers and the previous script, but what were some of those things in that crossroads?

Spaihts: It’s difficult for me to say very much about Prometheus without getting spoiler-y, so I’ll talk with some delicacy. I had the insight that if you were to try to reach back in time for the history of the universe we glimpse in the original Alien, you are inevitably concerning yourself with the affairs of non-human beings. Both the deadly predator that is the through-line of the Alien franchise and the enigmatic dead alien giant that is the great mystery at the beginning of Alien. Those are interesting entities not fully explained, but to keep an audience interested in those things it couldn’t be abstraction, it couldn’t be a purely “alien story” about things we can’t relate to. It was going to have to be connected to our own story. Somehow the story of those creatures was going to have to be connected to the human story, not just our history but our fate to come. I looked for ways to make those connections, and that’s where I got interested.

Filmmaker: Prometheus is in 3D, right? Did that format affect you as a writer, or was that purely on Ridley’s side?

Spaihts: I can’t say it affected me much as a writer. I was looking for a spectacle in any event because it was Ridley Scott returning to the Alien universe to tell a new story and to create a new mythology. So I was gonna go big, to look for visual spectacle in any event. You can’t work for Ridley and not find yourself embroiled in visual spectacle because that is his trade. I think where 3D really hits the creative process is at the storyboard level, where you break a narrative down to a series of shots and images. That’s where you really want to be able to compose the film both to take advantage of 3D and accommodate the burdens that 3D imposes on the viewer. There are quick-cut sequences that I think work in traditional flat film that are hard to watch in 3D. You need a little more time, as a viewer, to digest a 3D shot and to explore the frame of your eye. There are ways it calls for a different kind of cutting and a different visual composition. But that’s all in Ridley’s department. All I can do is sit over here being a fanboy and speculating about how he’s doing what he’s doing. It’s not really something I added to.

Filmmaker: Were you involved very much during the production process?

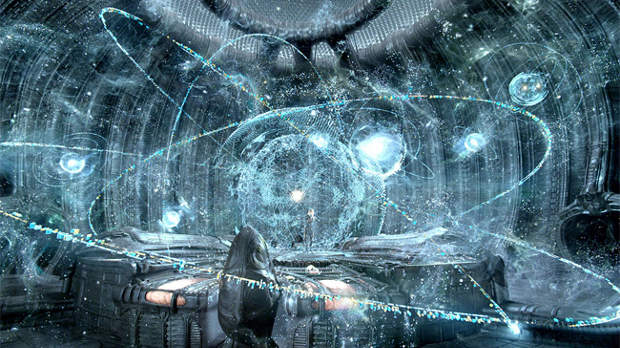

Spaihts: Yeah, we were in meaningful preproduction while I was still in the saddle, and Arthur Max, the production designer, had come aboard and was working in an office down the hall. He had at one point four different artists working for him around the clock. There were these beautiful moments where I’d hand in pages or just walk into his office and look at all the art up on the computer screen, the paintings, the 3D models, the stuff on the walls, and we’d talk about the scenes. I’d react to the art or pitch him the new scene, and we’d both talk about Ridley’s feedback, which was the guiding spirit of the entire film. The next day I’d come in, and stuff I had pitched the night before would be up on the wall as a four-foot wide painting of beautiful artistry and detail. The artists would have invented things and filled in details that I in turn would be inspired by and would then write into my pages. In the same way, Ridley would make sketches and diagrams of visual notions for me and I would incorporate them and hand him back scenes, he would respond again, and so I got to be in that beautiful whirlpool, that cycle of collaboration, the feedback cycle, and that was incredibly inspiring. It was the first time I had been really that deep into it and certainly the only time with a legend like Ridley Scott.

Filmmaker: I’m not sure how much I can ask about the movie because everyone is taking care to keeping to secret, but is there anything else you think would be interesting for us to know about Prometheus?

Spaihts: Well I can say I went to visit the set and was treated to the magical experience of walking around in locations that had their roots in my own imagination. I stood in rooms that I first wrote into existence on a page, and all of these of course were re-imagined by Ridley and his designers and his incredible creative team, but I got to see these things and these places and got to appreciate how much original movie magic is still alive and well in this age of computer graphics. Particularly on a Ridley Scott set — I think he prefers to do as much in camera as he can. And so the sets were cathedral-sized and stunning, and the rooms were exquisitely detailed. The costumes and props were perfect, and the lighting was beautiful. You could stand behind him in his director’s chair, put on your 3D glasses and look in his 3D monitors and the images you were seeing were ready for the Blu-ray. They looked perfect, ready to print, streaming live from multiple camera angles out on his sets because he is an old school practitioner of film making. He knows his light, his cameras and his frames; you can really see his gift in play right there on his sets. It was a real privilege and inspiration to see it.

Filmmaker: It sounds like you’ve made a complex movie, an ambitious adult science-fiction film dealing with intelligent, philosophical themes, and this is not really what’s being made these days. And it seems to me that you’ve been able to do this because you’ve come in under the mantle of this Alien prequel. But to some extent it seems like this could have been an original. If the original Alien didn’t exist this movie could have been invented. Am I correct in saying this was a little bit of Trojan horse? Or, to ask the question more directly, could a similar movie exist today if it was pitched as an original?

Spaihts: It would be a much harder movie to sell. Hollywood is constantly searching, it will tell you, for new ideas. But if you bring it a brand new idea, it scares the hell out of everybody. There’s a real trend in the industry right now to seek the reassurance of an existing property, known characters, known titles, known quantities. It’s hard to get the studios to invest in a brand new idea because that leaves everyone out there hanging in the wind. It means people have vouched for it standing on their own judgment. They can’t say, “Look it’s from this A-list writer, this series of A-list novels, that popular TV series, this incredibly popular cartoon.” They have to say, “I think this is good” — that’s all they have to hide behind. In the volatile industry of Hollywood that puts everyone at risk. It’s hard to punch through that apprehension, that nervousness about making big leaps into the unknown. In Hollywood’s favor, it still happens all the time. Originals are still being made and are still beginning blockbusters. But it’s always a fight, always an uphill battle. It takes a powerful patron to push those projects through.

Filmmaker: Do you think that’s going to change or is that the world we now live in?

Spaihts: I hope that we will relax a little bit in our mania for existing intellectual property. A lot of the great franchises of our day were born for the first time in a film. Luke Skywalker and Indiana Jones didn’t come from television or books; they were written to be movies. Likewise, the great characters of Hitchcock, and so many other filmmakers. So yes, I hope that we will have more faith in the ability of this medium to create.

Filmmaker: The movie has a very ambitious transmedia campaign. Did you have any input into that or was it entirely the marketing department?

Spaihts: I didn’t have a voice in the viral campaign that’s preceded the release of the film but I’ve enjoyed the hell out of it. I think most of it has been the brainchild of Ridley himself, and Damon Lindeloff, the writer who succeeded me. I’ve been a big fan of entire campaign, I think it’s extraordinary material, but it’s not a sandbox I got to play in just as a matter of chronology. But any world builder who creates a new universe and a cast of characters invariably has fleshed out backstories that will never be revealed in the film. And what could be more exciting for a storyteller of any kind to tell those extra stories, to flesh out the universe, to show you other pieces. And so if you’ve got a film, the anticipation of which justifies the creation of these ancillary materials, you just keep playing in the world you’ve made. For me, that’s a really exciting prospect.