Back to selection

Back to selection

Sundance Notes: Disarming a Film Festival

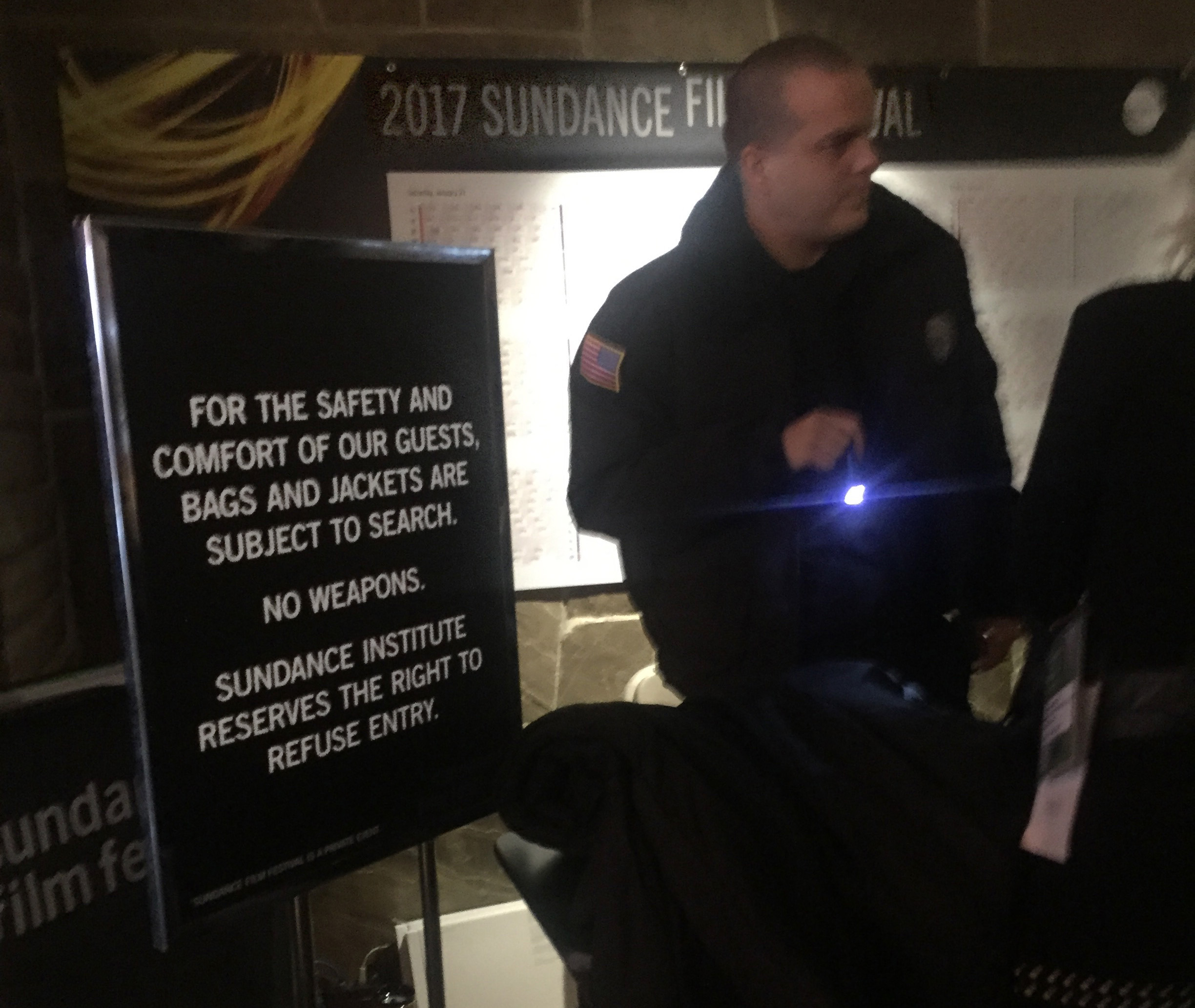

Prospector Theater, 2017 Sundance Film Festival. (Photo David Leitner)

Prospector Theater, 2017 Sundance Film Festival. (Photo David Leitner) On Friday, January 27, as I attended the second half of Sundance, Trump signed an executive order barring Syrian refugees and citizens of seven Muslim-majority nations from entering the United States.

“We’re not willing to be wrong on this subject,” said White House chief of staff Reince Priebus on Face the Nation two days later. “President Trump is not willing to take chances on this subject.”

The following Monday, The New York Times reported that senior White House officials “were proud of taking actions that they said would help protect Americans against threats from potential terrorists.”

This year at Sundance I saw 31 films. Most of them not in public screenings but in Press & Industry screenings, a viewership zealously vetted, on the journalistic side at least, by the Sundance Press Office.

31 times I was stopped while entering the theater, made to open both my overcoat and underlying jacket, made to unzip my neoprene laptop bag, then searched by flashlight. So was my partner, who wore additional outer garments because of the cold and always seemed to carry several bags.

We had just flown 2,000 miles from New York City, had already had our bodies, carry-ons, and luggage separately scanned and X-rayed at JFK Airport.

Was the concern that, as soon as I had landed in Utah, I would have dashed off to The Gun Vault or Get Some Guns & Ammo or some other Salt Lake City gun emporium and loaded up on firearms before that long schlep up to Park City?

If not, what then, actually, was the reason we were searched over and over again — at an elite film festival held in an expensive resort town?

My first Sundance was 31 years ago. A documentary filmed in Poland which I produced and sound-recorded was invited in 1987 to the Documentary Competition. I’ve since had seven other premieres at Sundance, documentaries and dramas, which I’ve directed, produced, or photographed (sometimes all three).

In years in which I haven’t had a film at Sundance, I’ve attended as a journalist. I’ve written about film and independent filmmaking ever since I reviewed George Lucas’s debut, THX 1138, for my high school newspaper. That first encounter with Park City and the Institute convinced me that the annual Sundance Film Festival would become a touchstone event in American culture, not just indie filmmaking. This was a scene I wanted to be part of, participate in, and experience first-hand every year.

Since 1987 I’ve missed perhaps two Sundances. I’m hedging, because I can’t really remember missing one over the years — but over three decades, I must have. I certainly did miss last year’s 2016 Sundance, because I was sound-editing a documentary I’d photographed (about Picasso) under an intense drop-dead deadline. The sort of all-in, last-minute dash you won’t forget easily.

That’s why the incessant security searches at this year’s Sundance came as a total surprise and shock. It appears this practice began last year — but I wasn’t there and was unaware.

Before I comment further, I want to state categorically that my comments in this blog are not intended as criticism of John Cooper, Trevor Groth, Keri Putnam, the Festival or the Institute. Because I have attended so many Sundance Film Festivals, I can say with a certain authority that the Festival has never been better conceived, better run, felt more inclusive or necessary. My hat’s off to them and their incredible staffs.

I grew up in the Deep South during the first Civil Rights era. Like Charlie Chaplin’s Little Tramp, I have a life-long aversion to cops. I don’t reflexively see them as protectors, so much as enforcers of the status quo and dominant power structure. Too ready to deploy that overbearing manner that comes from a badge and a gun or Taser strapped to your side.

To a hammer, every problem is a nail. To a law enforcement officer, every person is a potential perp. Uniformed rent-a-cops like those posted at every venue entry at this year’s Sundance, albeit unarmed, are cut from the same cloth as any other cop. In fact they often are the same cop. Some were undoubtedly off-duty and moonlighting from their day jobs.

When someone has the right to order you to open your clothing and to rifle through your personal belongings, in that moment they exercise absolute power over you. You can either accede, or at Sundance, be refused entry. Seeing as I had flown 2,000 miles to get there, I had no real choice.

But encountering what amounted to a security checkpoint at the entrance of the big white Press & Industry tent, I was truly taken aback.

So I did what any other documentary filmmaker would do under these circumstances. I began interviewing.

I politely but firmly asked the uniformed rent-a-cop what he was looking for. In my naiveté, I genuinely had no idea. Cameras to illicitly record what’s onscreen? Alcohol? I’ve attended film festivals around the world and have never been bodily or otherwise searched for anything, ever, not once.

The rent-a-cop glared back at me. I knew what that look meant. Don’t challenge my authority. Do what I say or else. Don’t tempt me.

I looked around. No signs explaining what they were looking for, or what items were forbidden inside the theater. Had I missed a press release from the Festival office about new security needs? Had there been a recent proximate threat or close call?

The cop wouldn’t say. My asking only triggered suspicion. I could see it on his face.

I was shaken by this encounter. It felt peremptory and wholly out of place. After all, all I wanted to do was catch a press screening, not board a plane or attend a White House cocktail.

I continued my interviewing in the days to come, if only to uncover what motivated this surge in security. Each time I entered the P&I tent, I tried to engage the uniformed person searching me and my partner. Some were friendlier than that first guy, though no more willing to entertain questions (as if told not to discuss policy with attendees).

Always I was polite, and one cop at the P&I tent eventually learned to recognize me. He once let me pass with a cursory glance. “I know you, you’re good.”

“Knives, guns… dangerous animals?” a light-hearted volunteer cracked one day, while my P&I check was underway. This was the first time it dawned on me that guns were the object of inspection.

Later, outside a public screening at the Prospector theater, I noticed a sign in front of the theater’s entrance, the first such sign I’d seen: “For the safety and comfort of our guests, bags and jackets are subject to search. No weapons. Sundance Institute reserves the right to refuse entry.” At last, a notice of explanation.

I spied a particularly diligent rent-a-cop checking people’s clothing at the theater’s return entrance, and struck up a conversation. I hit pay dirt.

He was in uniform like the others, a smaller man however, compact in build but wiry like a coiled spring. His intense, ever-watchful gaze didn’t miss a trick. He wore a thin mustache to match his short dark hair, several weeks past a regulation military cut.

He described himself as a “redneck” from Layton, Utah. I asked what exactly he was looking for. He told me hidden firearms. This was my first verbal confirmation that guns were the concern.

I thanked him for his candor, and he replied that he liked to talk about guns. He seemed relieved to have someone to talk to, who seemed interested. Ask me anything, he said.

I asked if there were an actual imminent threat, made by an individual. He told me not to his knowledge, but that screening for guns at Sundance had begun the previous year.

Had any guns actually been found? Yes, he said. He’d found two himself. In both cases people were cooperative about it. They had Utah permits to carry, they just didn’t realize that Sundance theaters had become so restrictive. In an effort not to miss the beginning of the film, they tried to sneak them in.

With pride he told me that he could even spot a gun hidden in the small of the back, because he’d tried that trick himself. Naturally, I followed up. How come? Where?

This opened up a conversation about carry laws in Utah. Whereupon I learned that to obtain a permit for “open carry” of a loaded gun, one must be 18, but for “concealed,” one must be 21.

[Some background: Utah was ranked the 4th most gun-friendly state by Guns & Ammo in 2015. No permit is required to own a gun, only to carry a loaded gun in public. If it’s not loaded, you can openly carry any gun in public without a permit. You also have a right to have a loaded handgun in your home or vehicle without a permit, even if you’re just 18. A law from 2004 enables anyone with a concealed permit to carry a loaded gun into any public school. Concealing a loaded gun without a permit is a Class A misdemeanor. You must be 18 to possess a fully automatic weapon or machine gun.]

He said he often carried a concealed gun, sometimes into places he shouldn’t. He didn’t elaborate much, mentioning only a big box store that once made him leave. He showed me how hiding a concealed handgun in the small of the back affects your gait, the way you move, adds a tell-tale bump to the back of your jacket. That’s how he caught one of the gun owners slipping into the theater.

He told me he’d spent two years with the Marines in Iraq as a military police officer. He’d killed exactly four people there. Stateside he’d been involved in two active-shooter situations where his firearm proved useful. In one situation on a military base, a PTSD victim shot four or five people, then discharged the gun into his own head. In another case, a soldier “lost it” on a firing range and begin wildly shooting at others. He had to shoot the soldier. Luckily he survived.

He said he lived for his gun collection. He even has an AK-47, he told me, which he fires in the desert. Next he wants to buy a military-style gun I wasn’t familiar with. With his thumb and forefinger he indicated a cartridge about an inch in diameter, which qualifies as an anti-materiel rifle or small cannon.

I asked how he could afford to fire off such a costly beast. He said “dry fire,” which is the honing of your trigger skills by “firing” a gun with an empty chamber.

My film about to start, I asked him, rhetorically, why would anyone pull a gun in a theater at Sundance? Had there been recent incidents in movie theaters in Utah? Not that he knew of, he said. He could recall only the 2012 mass shooting in Aurora, Colorado.

My final question: were other large public events in Utah hiring security guards to screen for guns? Yes, he said, it’s happening a lot now. Plenty of employment opportunity for him. He smiled a thin smile.

I knew how Diogenes felt. At last an honest man.

If indeed there were no recent incidents of mass shootings in Utah, if there were no imminent threats, why ratchet up the police presence?

Something to do perhaps with new requirements for events liability insurance in Utah? A stricter special event permit from the town of Park City? A higher bond? Whatever the case, this change in festival security couldn’t have been lightly implemented. There must have been discussion about it within the Institute. Hiring multiple shifts of unarmed rent-a-cops from CBI Security Services in Salt Lake and coordinating their daily schedules represents a significant expense, an additional budget line item for which additional funds would have to be solicited from festival sponsors, adding to the fundraising load.

Perhaps someone at Sundance argued against?

For what it’s worth, gun statutes in Utah’s 1977 Criminal Code preempt all local restrictions. They explicitly permit concealed weapons in public spaces, excluding only private homes and churches, and only then when prohibition is publicly posted. There is an exemption for “secure facilities” including airport, correctional, law enforcement, or mental health. That’s it.

In other words, Utahns have been carrying concealed weapons into theaters for decades. Since well before the founding in Salt Lake of Sundance’s predecessor, the Utah/US Film Festival. Utah, a Western state, has always advertised a robust gun culture. So what changed?

Was the new Sundance security policy because of upticks in Utah gun sales after Sandy Hook, or Obama’s executive actions in early January 2016 to crack down on Internet gun sales loopholes?

Was it a move in sympathy with, or fear of blowback from, the unofficial theme of last year’s Sundance, with its spate of films tackling gun violence?

Those who decide, independently of any immediate threat, to amp up security and impose a significant police presence on public events always wrap their actions in the mantra of public safety and precaution. They feel the weight of responsibility, they say, to protect their guests and patrons from “potential terrorists.” Because, what if?

“We’re not willing to be wrong on this subject,” they might say.

Thus begins another new normal.

In a page out of Mel Brooks’ Get Smart, a nincompoop flying from Paris to Miami tries to ignite a bomb in his shoe in 2001, several months after 9/11, and 16 years later an average 630 million people a year must still remove their shoes and belts to pass U.S. airport security. That’s over 10 billion pairs of stinky feet! With no credible evidence that anyone’s ever thought of weaponizing a shoe since.

Anyone born in the last 20 years might therefore be forgiven for thinking that doffing shoes at the airport has always been a necessary ritual for flying the friendly skies, as when entering a Buddhist temple.

Then there was the Underwear Bomber in 2009. We’d probably be dropping our drawers for the TSA if full-body scanners that rendered us naked to screeners hadn’t arrived in the nick of time. (In 2012, TSA scanners were required by law to replace our naked images with cartoons of us naked.)

Speaking of the TSA, CNN in a 2015 op-ed asked if the TSA’s $7 billion yearly cost was worth it, given that the agency had just missed 95% of the guns and bombs smuggled in a test of airport security by undercover agents of the Department of Homeland Security. Bet they wouldn’t have missed a single shoe, though!

The point is, each time we are required to surrender yet another little chunk of our personal dignity and liberty, what is the larger cost? And after the threat has passed, are these encroachments ever reinstated?

I mean, ever?

“Power [over others] is not a means; it is an end.” Well-observed, Mr. Orwell.

Maybe Sundance, if bent on continuing these personal searches, could borrow a page from the TSA’s playbook. Why not institute a Pre-Check program next year? Issue a special pass? It might feature the individual’s photograph hung on a lanyard around the neck. Start with all invited filmmakers. They may be a threat to public safety, but not because they’re carrying.

Continue with all accredited press. After all, they’ve already been tightly screened by the Press Office. Next, harmless industry veterans, who by definition have loyally attended the festival for years. Sundance Pre-Check, of course, should include festival staff and volunteers too.

Also, consider intelligent profiling, borrowed from Israeli airport security. Insofar as a mass shooting has never, ever, anywhere, involved a female — what’s the gender equivalent of gunman? — all women are automatically excluded from having to zip, unlatch, or unbutton their outerwear or expose the contents of their bags. What would be the point?

These helpful tips should enable Sundance to reduce next year’s outlays on security.

Let me be clear. I am not a gun advocate or apologist. I am not arguing for the presence of guns at a film festival. Heaven forbid.

I am arguing against public panic as a basis for policy.

I don’t want to see police checks and gun searches normalized at film festivals.

I don’t want to pretend that Sundance’s new “security theater” is OK. Unless, perhaps — pardon my dark humor — it’s curated by Shari Frilot’s innovative New Frontier as participatory performance art, something in the mold of Mexican artist Pedro Reyes’ wildly popular Doomocracy, produced by Creative Time in the Brooklyn Army Terminal on the eve of last year’s horror-show presidential election, which turned the surveillance state into a funhouse ride. In which case, I’d bet there’d be a long waiting line to get searched…

Nor am I willing to yield one more inch of the America I cherish, characterized not by author Barry Glassner’s Culture of Fear but by boldness and openness, where the privileges of personal liberty and individual privacy are held up as precious rights to be defended, not abrogated. Not chipped away one new “security” measure at a time. But perhaps that belongs in my next film.

What is a police state but a policed state?