Back to selection

Back to selection

SXSW: Five Questions for Spettacolo Directors Jeffrey Malmberg and Chris Shellen

Spettacolo

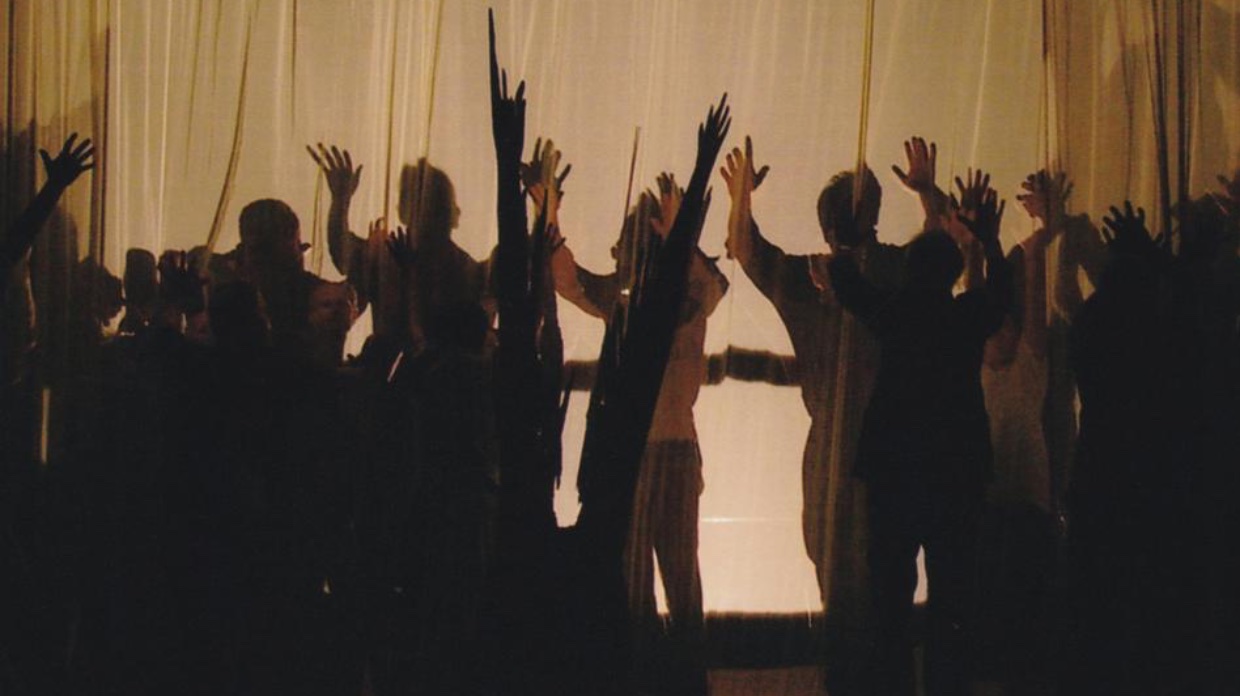

Spettacolo In Jeff Malmberg’s 2010 Spirit Award-winning documentary Marwencol, an artist constructs a one-sixth scale imaginary town, populated with miniatures, that is both his creative project and therapeutic enterprise; it’s through this work that he processes a violent attack that left him near-dead and brain-damaged. For the new Spettacolo, Malmberg, this time directing with filmmaker Chris Shellen, has focused on another individual for whom the world is a stage. Here, however, the scope is larger as theater director Andrea Cresti gathers each year the citizens of his small town in Tuscany to make a play based on their lives and histories. The filmmakers met Cresti while on their honeymoon and worked as a two-person team to capture the unique process of the town’s “Teatro Povero” (“Poor Theater”). The film premieres today at SXSW. Below, Malmberg and Shellen discuss the role of EU politics in the film, working as a tiny crew and how they incorporated their subjects into their filmmaking process.

Filmmaker: I know you’ve been working on this film for some time, and its production and post-production must have transpired alongside the recent political changes in Europe and the EU, including the migrant issues and rising nationalist tides. How did the contemporary political landscape enter the work you are documenting here — if indeed it did at all?

Malmberg and Shellen: Andrea Cresti (our main subject) told us early on that the town rarely comments on larger political events in their plays — they focus on the villagers’ experiences and reactions to those events. So we did cover the contemporary political landscape, but through the eyes of Monticchiello’s rural villagers.

At the time, they were concerned about issues like the banking crisis, government corruption, the loss of services for small villages like theirs, and the loss of funding for the arts — all issues that they’re still battling. So their play and our film focused on those. What was surprising for us was how universal and almost prescient the villagers’ experiences were. Everything the villagers included in their play has become more and more resonant in the U.S. today.

Filmmaker: How did you come across Teatro Povero in the first place, and what made them the subject of this doc?

Malmberg and Shellen: When we were in the middle of making Marwencol, we stumbled upon Monticchiello while we were on our honeymoon in Tuscany. The rest of Tuscany has become this kind of Disneyland of wine and cheese, but there was something immediately different about this town.

The only open door was to Andrea Cresti’s art studio. Inside was this man with this incredible face and presence. We just remember thinking that we wished we had our camera with us so we could shoot him. Eventually, we found out that he was the director of this really unusual theater in town, and the idea stuck with us. So once Marwencol was wrapped up and we had some headspace to think about the next one, our first conversation was, “Hey what about that little town in Italy….”

Filmmaker: In making Spettacolo, did you try to carry over any of the group’s “poor theater” concepts into your filmmaking, or to find cinematic analogues for them? Or to go in another direction? In other words, what ideas and influences informed your aesthetic choices as filmmakers?

Malmberg and Shellen: Well, we were a two-person crew, so I suppose you could call it “poor film!” That was sort of a surprise for the town actually. They were used to doing sort of Italian television hit-and-run news pieces about their theater that filmed for 20 minutes and then left, so the idea they we wanted to move there and stay for six months was really perplexing to a lot of them. Early on in the process, we actually had Marwencol translated into Italian, and we watched it with them in their small theater and talked with them about it afterwards. I think that’s when they finally started to understand our approach.

We wanted to copy their process in making the film, so we came in and we listened, and then we pieced together our impression of the experience and showed it back to them for their feedback. It was very important to us to include them along the way. That communication and discussion throughout the process is essential to their theater and it seemed like a great cue for us to think of them not as subjects to be studied but as true collaborators in the film. They were the first people to see a rough cut — we flew there to show it to them. After the screening for the whole town, they held a party in their church basement, and the entire group came together and started debating points in the film. We knew if we showed them the cut and they said, “Ah, yes, that’s very nice,” that we would’ve failed. You want a little friction there!

Filmmaker: What lessons did you learn from making Marwencol — whether those were aesthetic or in terms of the business or both — that you applied to the making of this film? And tell us about how you realized your film on a technical level — cameras, size of crew, etc.

Malmberg and Shellen: Aesthetically, the two films are fairly different. We believe the frame of a film should suit the subject. Mark’s real world was raw, grainy, and intimate, so the photography reflects that. Spettacolo is set in Monticchiello, on the other hand, one of the most picturesque locations in the world, so the film is designed to be more expansive and cinematic.

Jeff shot Marwencol largely by himself with a handheld camera, and it was crucial to establishing an intimate dynamic with Mark. We continued that on Spettacolo – it was just the two of us, two Sony EX1Rs and a Zoom sound recorder. Having no other crew or lights allowed us to be flies on the wall for their entire process.

The one big technical change we made was sound. It was easy to cover ambient noise and dialogue in Marwencol since it only has one main character, but in Spettacolo, we were covering four very different seasons and scores of characters, so Andrea dutifully agreed to be mic’ed the entire process, and we used a shotgun and other planted mics throughout town.

Filmmaker: Finally, what character in Spettacolo wound up making the biggest impression on you as a filmmaker and why?

Malmberg and Shellen:Andrea, hands down. He’s such a believer. We’re pretty sure everyone else in town was wondering what these two Americans were doing there, but he saw something in our approach. When we first made our pitch to the town, we told them that we thought their story was important and that people could learn from them, and everyone in the room laughed — everyone except for Andrea. They had been living with this tradition for so long that they were starting to take it for granted. But Andrea never stopped believing. And that’s always such a great documentary subject: a believer who’s being tested.