Back to selection

Back to selection

Interactive Video in a Gallery Experience: Lisa Truitt on National Geographic Encounter: Ocean Odyssey

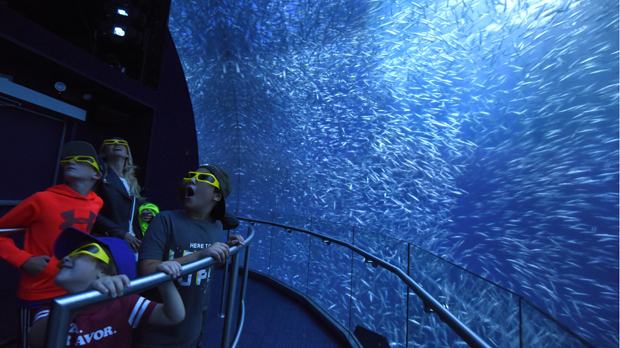

The 3D Bait Ball room at National Geographic Encounter: Ocean Odyssey

The 3D Bait Ball room at National Geographic Encounter: Ocean Odyssey For years the space at 226 West 44th Street in Manhattan was known as Discovery Times Square; it served as a tourist-oriented gallery space that housed temporary exhibits that alternated between artifacts like the Dead Sea Scrolls or Chinese terracotta warriors and contemporary pop—and film—culture like The Avengers, Harry Potter and The Hunger Games. By and large these relied on physical items and held little relevance to those interested in film and video. On October 6, however, the space reopened as National Geographic Encounter, and the first exhibit there, Ocean Odyssey, relies entirely on interactive video, motion-tracking gaming technology, 3D animation and intricate sound design to create a multi-gallery exhibit that will interest anyone concerned with expanding a film-like experience into a real-world space. Its immersive take on the traditional nature documentary genre is equivalent to, say, Sleep No More‘s take on a traditional performance of Macbeth.

The exhibit is made up of ten rooms, with a handful of visitors entering every few minutes (one downside is the inability to linger or proceed at your own pace, but this is presumably a necessity of crowd control and safety issues). The narrative arch through these galleries is a trip eastward across the Pacific, with shallow-water daylight episodes bookending nighttime events in the deep and open ocean. The first gallery is an orientation room with video presented on six screens. The second has a video projection on the wall and floor of the fauna near the Solomon Islands — fish, bluespotted ribbontail rays, spinner dolphins, a tiger shark — in which the animals react to your movements, darting away from underfoot if you try to step on them, for instance. Third, a coral reef at night features displays of bioluminescence on rocks and video screens; motion tracking allows you to create phosphorescent trails on the monitors. Fourth, the open sea at night is a nearly dark experience, despite two large video screens on the wall, that relies heavily on sound design to create the feeling on the open ocean. Fifth, a gallery with wall-sized screens on parallel walls allows two giant Humboldt squids to fight each other darting from one side of the room to the other, with their images projected on the ceiling overhead as they move past the viewers. Sixth is a kelp forest that relies on physical sculptures of kelp and, in a nod to old carnivals, a maze of mirrors, with kelp winding between the sheets of glass, that approximates the experience of swimming through a real kelp forest; the advice to pretend like you’re swimming with outstretched arms is apparently primarily to keep you from walking straight into a mirror, something I managed to do a few times anyway. The seventh goes from this low-tech experience to one that is essentially a video game: motion tracking connected with about five vertical screens allow visitors to control a California sea lion, as it copies your movements or obeys commands to spin, flip, or clap. Eighth is a simple ramp with a remarkable sculpture of a school of anchovies and an audio narration, but it essentially acts as a waiting area for the ninth room, which is a room with an enormous domed video screen (shown above) with a 3D animation of a bait ball — a group of tightly packed fish that predators like birds, dolphins and an enormous humpback whale attack. This is the climax, as the tenth and eleventh galleries provide informative videos about National Geographic and ocean conservation and individual games geared towards children, such as learning about a shark’s anatomy or cleaning up a polluted ocean environment. Near the exit is a station where visitors can make and share a video pledge to take concrete steps — there are several suggestions — to preserve the ocean.

National Geographic of course has a long history of exploration, conservation, and documentary filmmaking about marine environments (such as Mission Blue, for which I interviewed Sylvia Earle when it was released on Netflix in 2014), all of which was brought to bear on this new type of experience. With the release of the BBC Natural History Unit’s Blue Planet II on October 29 (it will air in North America in January) and a steady stream of virtual reality documentaries like The Click Effect, Journey to the Deep, Ocean Rift, and Under a Cracked Sky, National Geographic Encounter: Ocean Odyssey seems to herald a new age of marine nonfiction filmmaking, one that uses new tools and technologies to tell stories that could never be told before and that could have profound effects on public opinion on oceanic conservation precisely as the ocean enters its most critical period yet.

I interviewed Lisa Truitt via email about the exhibit and how her team put it together creatively and technologically. Truitt, who served as National Geographic’s President of Giant Screen Films and Special Projects, is now Chief Creative Officer and Managing Partner at SPE Partners, the firm which oversaw the creation of Ocean Odyssey for National Geographic.

Filmmaker: This is National Geographic’s first use of this space. What was the motivation behind taking over this gallery and creating a physical presence for the brand near Times Square?

Truitt: Located in the former New York Times printing press room, this is a first-in-kind immersive entertainment experience that pushes the boundaries of typical attractions by combining National Geographic’s incredible storytelling with an innovative blend of cutting-edge visual effects and technology, resulting in a new kind of entertainment experience. For the first time ever, people can walk through the iconic Yellow Border and step into a world they could otherwise never see. National Geographic Encounter is not a museum, exhibit, movie, aquarium, or virtual reality, but takes audiences on a breathtaking undersea journey across the Pacific Ocean that begins off the coast of the Solomon Islands as the sun is setting and ends as guests arrive on the West Coast of North America at dawn.

We needed a unique space and location to realize this vision, and Times Square was always our first and only choice to launch this. It took our team many years to find a suitable space with proper ceiling heights and volume to accommodate our technology needs. The fact that the building was designed to hold those huge newspaper printing presses meant that it had some large spaces inside — perfect for our needs. And we’re thrilled to be located in the “Crossroads of the World,” where we can reach both local and global visitors.

Filmmaker: National Geographic has a long history of making documentaries about marine life, and of course there’s now the Pristine Seas initiative as well. I noticed Enric Sala in one of the video interviews at the end of Ocean Odyssey, so I’m curious about the connection between this exhibit and National Geographic’s other ocean-related work. What do you hope visitors take away from your first exhibit here?

Truitt: Encounter is a powerful way to bring science to life and also plays an important role in raising awareness of the vital importance of keeping our oceans healthy. Every part of Ocean Odyssey is scientifically accurate, and we worked with dozens of National Geographic scientists, researchers, and photographers in its creation, including Enric Sala. In fact, blockbuster new science — some of it not even published yet — was used in its creation. We worked very closely with marine biologist, professor, and National Geographic Explorer David Gruber, who was the Chief Science Advisor to the experience and who specializes in bioluminescent and biofluorescent marine animals.

Our mission at SPE Partners — the creators and producers of National Geographic Encounter — is to deliver breakthrough shared entertainment experiences that inspire people to make a difference, one encounter at a time. We do this by creating what we call “entertainment with purpose”: lots of fun, with substance behind it. We set out to push the boundaries of storytelling and create a new kind of experience, taking guests out of their seats, allowing them to walk…and share stunning ocean encounters with friends and family. At the same time, we hope they will come away with a new understanding of the richness and complexity of ocean ecosystems.

Many of us look at the ocean and see a flat surface. Yet, the ocean covers 70% of our planet and is full of so many amazing things that very few people will ever see with their own eyes. We want to cross that boundary and take people to this incredible underwater world. We want to take them to places they might never have the chance to go. Perhaps even more importantly, we wanted to create something that enables people to form an emotional connection to the ocean, which can generate a real appreciation for not only its beauty, but for the need to love and care for it. It’s human nature to care for what we love. So, if this experience can create a love for the ocean, then we have a much greater chance that we, as a collective whole, will care for it. That is what our fragile ocean needs.

Once guests have experienced Encounter, we find they are very interested in some of the amazing work that National Geographic supports, including the work of Dr. Gruber and Dr. Sala, which is featured in the experience. Sala in particular has a very ambitious goal of working with governments to create huge new marine reserves — and he’s been stunningly, wonderfully successful. This kind of good news story is great to share with our guests.

We also give visitors the opportunity to participate in ocean protection. Everyone who goes through Encounter is invited to take an individual pledge to take action for ocean conservation. We want guests to feel empowered to know that small steps they take can make a huge difference in protecting our ocean.

Finally, many visitors are choosing to “round up” their purchases in retail. That “change” will be donated back to the National Geographic Society to fund its ocean conservation initiatives, including Enric Sala’s Pristine Seas.

Filmmaker: What was the design process like for the entire space? How did you decide which habitats and creatures to include and which forms of video and technology to use to display it?

Truitt: My partners and I pulled together a world-class global team of Academy, Grammy, and Emmy Award-winning artists, including the design firm Falcon’s Creative Group (show design), and for our photoreal animation we turned to Pixomondo, the visual effects team behind Game of Thrones. The team also includes Grammy award-winning producer and composer David Kahne (sound), as well as Mirada Studios (video production), our technology integrator, Kraftwerk, lighting design by Lightswitch and set design and fabrication by Adirondack Studios.

With those folks and our science team, SPE hosted a charrette, at which we brainstormed everything from the basic, almost existential questions (What should Encounter be?) to storylines (What journey should we take?) to technology (How should we bring this to life?). SPE worked hard to unite the teams under one vision, and in doing so, we pushed boundaries in many of these individual specialties. We were proud and thrilled at how beautifully our creative group came together, enthusiastically uniting around the mission of creating something truly new.

SPE always wanted Encounter to be story-driven and to showcase some of the most amazing natural behavior that’s ever been witnessed in the ocean. And of course our number one ground rule was that everything had to be scientifically accurate. So we assembled a “wish list” of amazing possibilities, and then figured out that all of our favorite scenes could actually happen in the Pacific Ocean. We devised a journey around that, and incorporated a day-to-night-to-dawn through-line in the experience. It works well.

As a teenager, I learned to scuba dive in the kelp forests off the coast of California, and have done many hundreds of hours of additional diving in the Caribbean and off Hawaii. I’ve been lucky enough to witness nature at its most extraordinary in a long career at National Geographic (prior to joining SPE Partners). So, personal experience played a role in figuring out what animals to portray and how to bring all that to life in Times Square!

Once we knew our story line, the next challenge was to figure out the best way to bring that to life. After much analysis, we chose to create most of the visual elements through photo real animation. We made this choice for a number of reasons:

- First, from a practical perspective, we needed visuals that had enough resolution to fill entire rooms without getting grainy. There’s very little live-action footage available at a high-enough resolution for it to hold up in our spaces.

- Secondly, these situations — such as an intense battle between two Humboldt squids, or the magnificent creation of a bait ball — occur naturally in the ocean, yet are extremely difficult to capture on film. And the camera systems that can capture footage at super-high resolutions haven’t been around long enough to afford filmmakers the opportunity to capture the very rarely seen behaviors that we depict in Encounter.

- Third, the imagery had to be rock-solid steady. With projection on floors and ceilings, it’s easy for guests to feel like the room itself is moving. And were we to use live-action photography, the natural rock-and-roll of the camera system would be truly unpleasant for our guests.

- Finally, by using animation, we can give everyone the opportunity to get very close to some of the ocean’s largest and most interesting creatures at true-to-life-size and with exact scientific detail.

Filmmaker: So a great deal of work went into the visuals of the experience, and it would be easy to overlook the importance of the sound design, even though that plays just as large a role. Perhaps the room of the open sea at night relies the most heavily on sound. Can you tell me about the sound (and visual) design that went into creating that space?

Truitt: We knew that sound would be critical to ensure the environment felt immersive, so we chose to create a score using real underwater sounds and enhance it with music. Grammy award-winning producer and composer David Kahne (who has produced records for Sir Paul McCartney, Billy Joel, Bruce Springsteen, Tony Bennett, Sublime, Kelly Clarkson, and many others) collected sounds from libraries all over the world to create a state-of-the-art experience featuring a majestic ocean soundscape which graces the entire space across 230 loudspeakers and 180 independent channels.

In the room you asked about, we wanted to capture the disorienting experience of floating in the ocean at night. All around you is blackness, with maybe a glimmer of moonlight if you’re close to the surface, and the twinkling of tiny phosphorescent planktonic creatures around you. Light doesn’t travel far in water, but sound can travel vast distances. And so all around, you can hear the amazing sounds of ocean creatures, which the very talented David Kahne brought together into a kind of “ocean symphony.” The idea was to enable guests to “see” the night ocean with their ears, and to get a taste of what it truly feels like to be offshore in open ocean at night.

Filmmaker: My children really enjoyed following the dueling Humboldt squids that you mentioned as they chased each other from one wall to another. What was the animation process like to create that video on two parallel walls and even the ceiling overhead?

Truitt: That one was indeed a challenge! The overall idea was based on video captured by the National Geographic “crittercam” team, who temporarily attached a camera right onto a Humboldt squid. The scene in our space was inspired by the footage that camera captured, as well as by the stories of diving with Humboldt squid that photographer Brian Skerry has shared with us. Both sources capture how the squid come out of the blackness, their pulsing light announcing their presence as they rocket around you. It’s very weird and otherworldly.

To create the animation, we had to map out the action from an overhead view, as if you were looking down on the room. That allowed the animators to figure out when each squid would leave one screen, travel across the ceiling, and then enter the opposite screen. We watched that overhead view side by side with the two different “screens.” Watching and trying to judge that on a computer monitor was really difficult, and so our animators also rigged up a small-scale mock-up of that scene which allowed us to actually stand inside a physical space and feel how the flow worked. We also created a virtual reality version of that scene and others, so that we could get closer to imagining how it would feel to be in an actual space. Finally, we also mocked up screens in a warehouse in Austria, which allowed us to test the multiple high-resolution projector set-ups. All of this got us through the time period when the space itself was under construction, and we had no “real” space in which we could adequately rig and test our footage.

Filmmaker: It’s interesting all the work that went into something like that, because perhaps my daughters’ favorite part was the mirror maze designed as a kelp forest, which was also the lowest-tech component of the entire experience. How does a gallery like that relate to the other spaces that feature cutting edge video and motion tracking technology?

Truitt: As I mentioned earlier, I learned to scuba dive in the kelp forests off the coast of California and I remember well how disorienting it can be to swim through one, like swimming through a vast cathedral full of columns of kelp. The use of the mirror maze was an effective and fun way to convey this sense of vastness for our guests. We combined an age-old carnival trick with high res footage on multiple video screens interspersed with the mirrors, so that the animals of the kelp forest would reflect in the mirrors and “populate” the maze. We also added the sounds of the animals of the kelp forest, and some moving “caustic” lighting to create an experience that audiences just love. We ended up with an original twist on an old trick, with the tech part of it playing a more of a “supporting” role.

Filmmaker: Can you tell me about Ocean Odyssey’s use of motion tracking, because you use it in a few different ways? It’s used in the first room with fish and rays in the shallow water of the Solomon Islands, with bioluminescence in a coral reef at night, and in controlling an individual California sea lion character off the west coast of North America. What was different or the same about all of these experiences?

Truitt: They are all twists on the same idea, but each had to be programmed and individualized to be effectively used in each space. Obviously every scene tracks visitors from different vantage points. For tracking on floor surfaces, we had to use multiple projectors to minimize the interference of shadows. And then in each space, our animation team wrote a great deal of software to get the intended effect. With the sea lion in particular, we were aiming to make the sea lion act almost like A.I.; each one reacts slightly differently, and they seem to have individual personalities.

Filmmaker: Can you tell me about the final room? It uses both a curved/domed screen and three-dimensional projection to create as immersive an experience as possible. Viewers stand on a platform extended into the space so that they see 3D animation above them, below them, to the sides, and, through some mirrors on the rear wall, even behind them. How did the visual, aural, and physical components all come together to achieve that affect?

Truitt: The 3D Bait Ball scene is a real guest favorite. This is one continuous shot, nearly four minutes long, and is a unique piece of content. It was created at 8K resolution and at 60 frames per second in 3D in order to give as much clarity and realism to the scene as was technically possible. So, each second of 3D footage in this scene contains 120 frames, each of which took up to a day to render because of the very high resolution; the entire scene has roughly 14,000 frames. We used facilities in multiple countries over a period of several months just to render this one shot at such. Our Emmy and Academy-award winning animators aren’t aware of another single shot ever created that has so much data. In fact, the head of our visual effects team said that creating this scene was a ‘game changer’ and one of his biggest visual effects challenges to date.

Filmmaker: Were there any unforeseen challenges that you had to overcome or that will influence the next exhibit you create in this space?

Truitt: The biggest challenge was finding a venue/real estate with a footprint capable of handling our immersive layout so as to accommodate a seamless guest flow of up to 25 people every five or six minutes, as well as allowing our designers to build and install a 40-foot dome.

The other challenge was designing an immersive experience within the confines of architecture. We had to deal with ceiling heights, columns, and other structural limitations and we had to figure out the workarounds to make these things essentially “disappear.”

Then we also had building codes. So for example, we had to find a material from which to make simulated kelp, but it had to meet NYC fire code standards while still achieving the right look. We went through five or six options before we found something that was acceptable aesthetically, though it didn’t have the softness we’d originally wanted.

Finally, it was an unbelievable challenge to create media for giant spaces that didn’t yet exist, and for which we had no space in which we could accurately test the media during creation. That a lot demanded patience, and ingenuity!

The good news is that when we bring another theme into this space, we will have already tackled these challenges, so that integration should be much simpler. But of course, there are always surprises!