Back to selection

Back to selection

“Making a Good Movie Has to Come from the Heart, Not from a Mental Understanding of an Issue”: Matthieu Rytz on Anote’s Ark

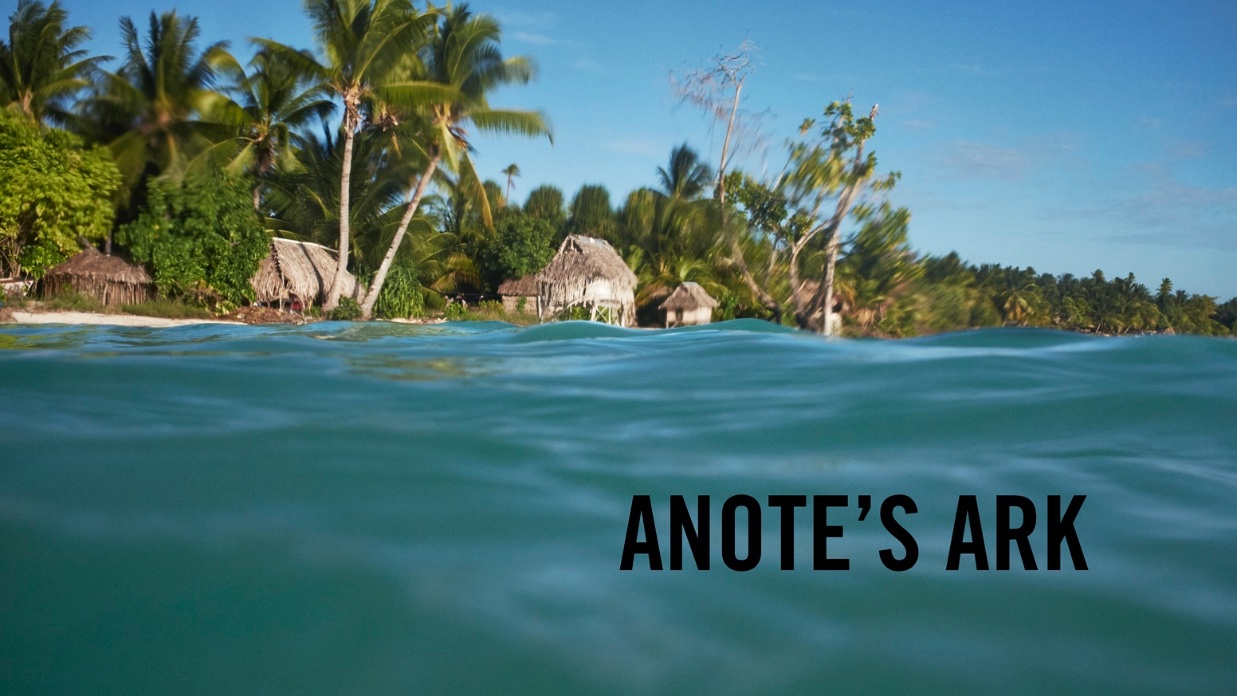

Anote's Ark

Anote's Ark Premiering at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, Matthieu Rytz’s Anote’s Ark follows the international, one-man crusade of Anote Tong, president of Kiribati. That island republic is situated smack in the middle of the Pacific with an indigenous population — exemplified here by Sermary, a young mother of six forced to choose between family and a future in New Zealand — poised to lose their 4,000 year-old way of life as climate change will soon cause the entire country to disappear into the ocean. As the title implies, Tong is less concerned with saving Kiribati itself — he’s painfully aware it’s too late for such fanciful idealism — than in a mass relocation of its citizens to a new shared homeland. That, and in sounding the alarm that Kiribati is merely the canary in a global coalmine.

Filmmaker spoke with the Swiss director, who trained as a visual anthropologist before turning to photography and documentary work, prior to the doc’s NYC premiere at the Human Rights Watch Film Festival (June 15th at the IFC Center, June 18th at the Film Society of Lincoln Center).

Filmmaker: So how did you come to this story? There are many islands facing extinction due to climate change — Kiribati being one — but it’s also a nation I’m guessing few people even knew existed in the first place.

Rytz: I started the whole project as a photographer, initially covering the global issue of the rising sea on assignment for The New York Times. There are indeed a few places in the world that are affected, but only the Marshall Islands, Tuvalu, and the Republic of Kiribati are entirely made of atolls with an altitude of only one meter above sea level.

I went to the Guna Yala (formerly San Blas) in Panama where they are experiencing huge losses of lands, too. Then I basically took the map of the Pacific and started learning about those nations. When I discovered that in the middle of the ocean there’s this country called Kiribati with an oceanic border the width of the US that I’d never even heard of I was amazed. I told myself that I definitely needed to start working on Kiribati’s issue.

Filmmaker: I actually experienced the VR companion piece (at Hot Docs) before I watched the film. Can you discuss why you decided to create this in addition to the doc and how that experience differed from shooting the film?

Rytz: While I was travelling with the president, Anote Tong, he was always telling people, “Please come and visit Kiribati so you can witness the issues for yourself.” By saying this, he is making a very important point that Kiribati is absolutely on the frontline of climate change. Most people don’t really understand what that means as they are not really affected by it. The very survival of the people of Kiribati is at stake.

So I thought that by using VR technology it would help people understand the reality of what is happening in Kiribati. VR is an incredible teleportation machine that allows people to witness reality in a way that traditional documentaries can’t. I think it’s a very good companion to the movie, as it allows people to virtually travel to Kiribati after they watch the film. Ultimately, I hope it will build a sense of empathy towards the people of Kiribati, see the faith they have.

Filmmaker: As a non-indigenous filmmaker how did you gain the trust of your subjects? Were they wary of an outsider coming in to tell their story? Did your ethnology background help?

Rytz: In order to gain the trust of my subjects there wasn’t any special trick, but only one fundamental ingredient — time. As a white, privileged, straight man I couldn’t just show up in the most remote place on the planet and pretend that I know them and what they are going through.

The only way to be truthful with the process was to have a lot of patience, and to keep going back again and again. That’s why it took me four years of filming. The most important thing was to work very closely with the people I was filming. It was extremely important for me to have a good representation of Kiribati culture. But I also quickly realized that I had this huge responsibility to tell Kiribati’s story to the world, as it will be the first major documentary on the subject, with a widespread audience.

I suppose having an ethnology background helped me in the process of representing “the other,” and in the intellectual understanding of post-colonial issues. But ultimately, making a good movie has to come from the heart, not from a mental understanding of an issue.

Filmmaker: As your title implies, (now former) President Anote Tong is at this stage more focused on getting his people relocated, as he believes it’s too late to save Kiribati. Is there tension between islands (and islanders) that idealistically want to stay and fight to save their homeland versus the realists who understand that regardless of what they do it’s just a matter of time before that homeland disappears?

Rytz: It’s a very complex question. The scientific data is saying that all of the island will be submerged within the century, and that we have already passed the tipping point. Basically it means that it’s too late for Kiribati, and that regardless of what the world is doing to bring down emissions they will have to be relocated.

On the other hand, the rise of the sea level is gradual — and most of the islanders don’t have a foreign education that can give them the intellectual tools to understand modern science. They are connected to nature with an empirical understanding of the changes around them. They do absolutely see that things are changing, but it’s very hard for them to believe that it will get to the point where their homeland will become inhabitable. So yes, there is a tension between traditional knowledge and modern science.

Adding to that is the fact that lately a lot of Mormons are coming to all of the Pacific islands with a lot of financial support to convert people. The conversion rate is very high. And unfortunately, Mormons are climate change deniers, and are teaching the people of Kiribati that they don’t have to worry about climate change since God will ultimately take care of them.

So in order to keep a strong electoral base, the new government is now embracing climate denier rhetoric, and is fighting against Anote Tong’s legacy. Of course, this also happens in the US, Australia, and in other parts of the world where climate change is being used for electoral purposes. But as Mr. Tong is constantly saying, “Climate change should not anymore be taken as a political issue, because it’s about the future of our humanity that is at stake.”

Filmmaker: I assume you have an impact campaign planned? How are you reaching policymakers that can actually make a difference with regards to climate change?

Rytz: I don’t have a specific impact campaign planned yet, as most of my work has involved supporting Anote Tong’s campaign that has been in place for over ten years. Mr. Tong is also traveling with the movie, and his presence has become a very important tool in continuing the fight.