Back to selection

Back to selection

Focal Point

In-depth interviews with directors and cinematographers by Jim Hemphill

“Imagine How Angels Would Look at Us”: Wim Wenders on Restoring Wings of Desire

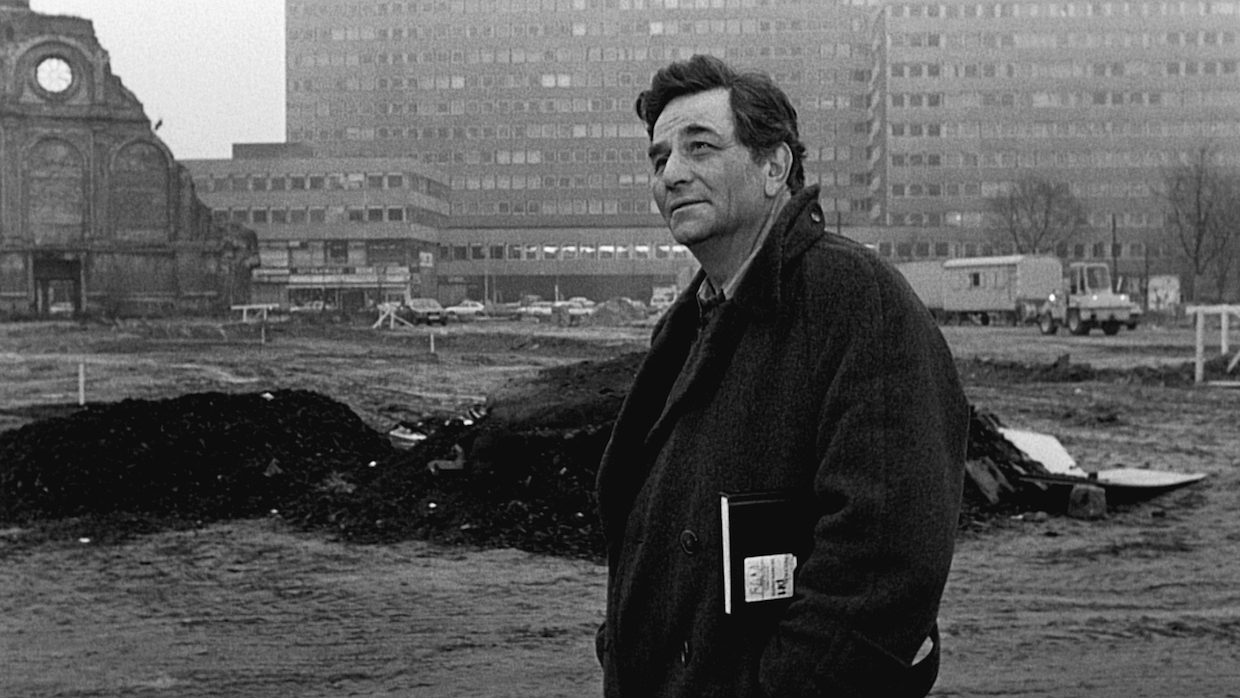

Peter Falk in Wings of Desire

Peter Falk in Wings of Desire As a longtime Wim Wenders fan and devoted admirer of his masterpiece Wings of Desire, I would never have thought it possible that the movie could look better than it did when it was released in 1987. Gorgeous in every sense of the word, from the shimmering black-and-white photography of Henri Alekan (the maestro behind Jean Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast who Wenders prodded out of retirement to shoot the film) to the profoundly romantic story of an angel who wants to fall to earth and experience the human condition, Wings of Desire was a stunner when it came out and it’s only gotten better with age. Its level of ambition and accomplishment is staggering, as Wenders combines lyrical fantasy, intimate character study, and an epic portrait of a city and its culture without shortchanging any of these disparate elements—it’s a movie for the head, the heart, and the eye that ranks with the greatest achievements in the history of cinema. Yet Wenders and Alekan had always been dissatisfied with the ways in which the technology of the time compromised their intentions, a problem that has been rectified by a beautiful new 4K restoration currently playing at Film Forum. On the eve of the release I interviewed Wenders about the making of the film and its restoration, and I began by asking him what prompted a return to life and filmmaking in Germany after several years in America, where he directed his 1984 Palme d’Or winner Paris, Texas, among other great movies.

Wim Wenders: A very simple and basic thing: after seven years of living in America, I started to think (and dream) in English. I noticed the effect with lots of immigrants; they slowly lose their first language. I didn’t want that to happen. And also, my seven years in San Francisco, Los Angeles and New York had taught me that I could never become an American, let alone make “an American film.” I was a hopeless German romantic in my heart, and a European filmmaker by profession. Apart from Hammett, which had been a studio production by American Zoetrope, my other films in the US at the time (Lightning Over Water and State of Things) had been financed and produced out of Germany anyway. Paris, Texas, too, was strictly a French-German coproduction. So I figured it was time to go home. And home was not really Germany as such, but the city of Berlin. That was where I wanted to go back to. I had my production company, Road Movies, there from 1974 on.

At first, after Paris, Texas, I tried to get the film off the ground that I had interrupted in 1977, when Francis Ford Coppola had invited me to come to San Francisco to do Hammett. That was a science-fiction film which later became Until the End of the World. After trying for two years and traveling extensively to Australia and other remote parts of the world, I realized that this project would need much longer to finance and prepare. And I hadn’t shot a film for almost three years. So I felt the itch to make a film soon, and very spontaneously so.

Filmmaker: Given that Wings of Desire is such an ambitious film, both conceptually and visually, I was surprised to hear that it came together rather quickly. How did the idea first come to you, and what were your initial steps toward writing a script?

Wenders: The idea strictly came from wandering around Berlin and feeling inspired to make a film that would tell the story of a city that had seen hell, and that was now a very unique place on Earth, an island city divided by a wall. A film that would show as many aspects of this city as possible, and that would also go diagonally through its history. I was looking for characters through whom I could tell the city, because I didn’t want to make a documentary film. Fiction is the best way to preserve places, I feel. I thought of firefighters and mailmen and God knows what sort of people, and I finally ended up with the only idea left that would allow me to explore the city in almost infinite ways: with the help of some guardian angels. And one of them would fall in love with a woman and decide to become a mortal. The angel idea was really suggested by the city itself, so to speak, as it has those angel figures everywhere, and by my nightly reading of Rilke poems. As I was trying to find my German language back, Rilke seemed the best teacher. And his poetry is inhabited by lots of angels.

Filmmaker: How did the script evolve once you brought your co-writer Peter Handke on board?

Wenders: I traveled to Peter, who was living in Salzburg at the time, to ask him for help. He listened to my story, as little as it was, of guardian angels, of a trapeze artist in a circus, of those angels watching us people without being able to interfere, listening to our thoughts. At the end, Peter shook his head. “I can’t help you with this. You have to face that music yourself. And besides, I’m deep in this novel and don’t want to interrupt it.”

So I traveled home. I tried to write for a while, but realized it would take an eternity. Solveig Dommartin had learned all she could learn on a trapeze, I had the greatest director of photography in Henri Alekan, and two fabulous actors with Bruno Ganz and Otto Sander. I figured I could just as well start without a script. The material was so strange and “poetic,” for lack of a better word; any plot or any elaborated story could only ruin it. So I started from one day to another. All I had was a wall full of pictures of all the places I knew I was going to shoot in, and another wall with ideas for scenes. Endless ideas. These angels really were an abundant source of scenes you could imagine. We really shot on a day to day basis.

Then a little miracle happened. I got a big envelope in the mail with about 20 pages. Peter had felt bad that he had sent me away without anything, and he had written a dozen dialogues—well, some of them were monologues—about scenes he remembered I had told him about. The first time the two angels would talk about their day’s work and compare notes, the first time the woman and the newly-born man/ex-angel would meet, another long dialogue of the angels walking through the city, and a handful of interior monologues for the character Peter had liked best, some sort of arch-angel of story-telling whom he had named “Homer.”

So all of a sudden I had these dialogues that Peter had written on spec, without really knowing if they would fit or not, and they really saved me. The film overall was like flying without instruments, at night, but every now and then there was a lighthouse, and it was a scene for which I’d have great words. That’s how we fought our way through the entire film. Lots of nightly writing, lots of improvisation, and every now and then the actors had some real solid dialogues.

Filmmaker: What were some of your literary and cinematic influences on the film?

Wenders: Well, there was Rilke. No other literary influence other than that, and Peter Handke, of course. And in terms of movie influences, I dedicated the film to my three “archangels,” Truffaut, Ozu and Tarkovsky, because they had all ventured into such “transcendental” territory. But I don’t think I had any particular film in mind that influenced us.

Filmmaker: The film has so many striking deep-focus compositions, and I’m wondering if you could talk a little about the choice to shoot primarily with wide lenses.

Wenders: We shot Wings on an ARRI 35mm-camera, a BL (yes, just one) and used Zeiss primes. The bulk of the film was shot on 28mm or 32mm lenses, but for close-ups I usually went for 40mm or 50mm. The use of any other lenses was extremely rare, maybe inside the WWII air-raid shelter we used a wider angle for some establishing shots. With very few exceptions (like for a “Vertigo-effect”) I do not carry zoom lenses in our equipment, as I basically never use them for their zooming capabilities. And as you have a better optical result on prime lenses, I stick to those.

Filmmaker: What was your philosophy about camera movement and blocking in Wings of Desire?

Wenders: As we very often had to “translate” the angels’ point of view, so to speak, we were extremely keen on moving the camera as much as possible. In the absence of Steadicam equipment we worked a lot on tracks, with dollies, cranes, jib-arms etc. But we also built ourselves devices so we could move through the air from one house to the next, for instance, and we shot the opening sequence on a helicopter, which was highly difficult in West Berlin at the time, as there were no private companies flying, just the Allies with their respective army pilots. We ended up shooting with a British pilot in an army helicopter without a proper camera mount. Today, you would do these things with gyroscopes and such.

Blocking has always been my department. Henri kept out of it completely, and I did it with his operator, Agnès Godard. I have done shot lists for complicated sets, but usually I decide on location in the morning how we design the shots. I prefer to see the actors rehearse it, before I commit to any blocking.

Camera moves weren’t the real challenge, though, for finding the angels’ points of view. It dawned on me early on that our camera had to do a more complex job. I told it to Henri. “Those angels have a very loving look at us humans. We have to find a way to teach our camera to look more lovingly.” Henri just stared at me as if I was out of my mind. “How do we do that?” Well, I didn’t know of course. But I figured we had to invest more care and love ourselves into every shot that represented what the angels saw. And that’s it, in the end. A camera can reflect on what you invest into its act of seeing. That sounds pretty lofty, I guess. But it does rub off, I tell you, if you try to imagine how angels would look at us. After all, they were some sort of metaphor for me for the better persons we carry inside ourselves, or for the children we somehow preserved in ourselves.

Filmmaker: Given what an unusual story this was, was it difficult to raise financing?

Wenders: That wasn’t too difficult, given that Paris, Texas had been such a success. I got a lot of credit, so to speak. But I really didn’t want to repeat myself, so with Wings I made a film that was the sheer opposite.

Filmmaker: I love the idea of Peter Falk playing himself as a mortal man who was once an angel. Where did that idea come from?

Wenders: Peter’s part was never scripted and came as an afterthought. We were already shooting for two weeks, when my assistant Claire Denis and I were brooding again one night in front of our walls with photographs and scene ideas. I said to Claire: “Don’t you think these angels take themselves too seriously? Don’t you think we’re lacking some humor in this production?” She nodded. That night, we came up with the idea of an “ex-angel” who would have gone through the exact experience that Damiel was going through, a man with a “sixth sense” for any angel who’d be tempted to make the leap. And that night, we came to the conclusion that Peter Falk was the ideal cast. And that night, through some miraculous help by some angels who had their hands in this, I got Peter’s number from John Cassavetes, and that night Peter answered the phone, laughed his heart out at my silly proposal to come to Berlin right away and play the unscripted part of an ex-angel, and said the most beautiful thing I ever heard from an actor: “Okay, I’ll be there this weekend. You know, I did my best work this way.”

Filmmaker: Did Falk have any involvement in writing his own internal monologues that we hear as voice-over?

Wenders: Peter was in a recording studio in Los Angeles, I was listening on a line in Berlin. I had written a few pages of interior monologues for him to try. He went through it, and eventually said: “You know what, Wim? I’ll stop reading your lines and just close my eyes and give you some rambling thoughts. You’ll find something in there.” And then we recorded for half an hour, non-stop. It was all I needed—except that a lot of Peter’s thoughts involved his grandmother. We laughed a lot when we realized that ex-angels don’t really have grandmothers. I still used some of it. It was just too good.

Filmmaker: What kind of work was done in the new 4K restoration and sound mix?

Wenders: In order to answer the question properly, I have to quickly explain where we were coming from with Wings of Desire. The film was shot in 1986/87, so it was obviously all done on 35mm film. Three quarters of the film were shot on black and white negative, one quarter (especially the ending) on color negative. Those color elements appeared in each of the 7 reels, due to the underlying idea that the angels would be seeing the world in black and white, while people were seeing it in color.

Technically, to make a long story short, that meant that the entire film had to be printed from a color negative, as the film also contained complex visual effects (all done on film, of course). This meant that the first combined print of the film was six generations removed from the camera negative, the Cannes festival print just as well as any other print since. Now, you can imagine that in the analog age, six generations represented a huge loss of detail and resolution, but most of all it meant that Henri Alekan’s gorgeous black and white was no longer printed from a black and white negative, but from a color negative that had already been duped several times. Our director of photography—after all, the authority in the world on black and white film—was heart-broken, and me, too. I had seen the splendor of Henri’s black and white in our rushes, every night after the shoot, but that was all gone in the prints. All black and white scenes now had a slight bluish or sepia touch, necessarily so. We made the most of it, of course, but had to live with the result that only Henri and I knew was far from what we had dreamed of.

30 years later, in the digital age, we could finally rectify this. We scanned the entire film from the original camera negative (which we had saved, each and every bit), and then had to redo each and every cut, as well as every optical and visual effect, and thus rebuilt the entire film, identically, frame by frame, only that it was now from the very negative that had run through Henri’s camera. The difference is stupendous, and only seeing is believing. Henri, watching it now from cameraman’s heaven, is happy, and so am I. The film does not differ from the original, not in a single frame, but it just looks infinitely better.

It also sounds better. Wings of Desire was my first film in stereo at the time. But today’s standards are much better than what we were able to mix in 1987 on tape and on optical sound. As we still had all original tracks (better: tapes) and as the music was recorded in stereo anyway, we were able to be completely true to the film’s original soundscape and not only present the film in 4K now, but also in contemporary 5.1 stereo.

Jim Hemphill is the writer and director of the award-winning film The Trouble with the Truth, which is currently available on DVD and Amazon Prime. His website is www.jimhemphillfilms.com.