Back to selection

Back to selection

“High Security Was Essential, In Order to Protect My Sources, My Crew and the Ability To Complete the Film”: Alex Winter on The Panama Papers

The Panama Papers

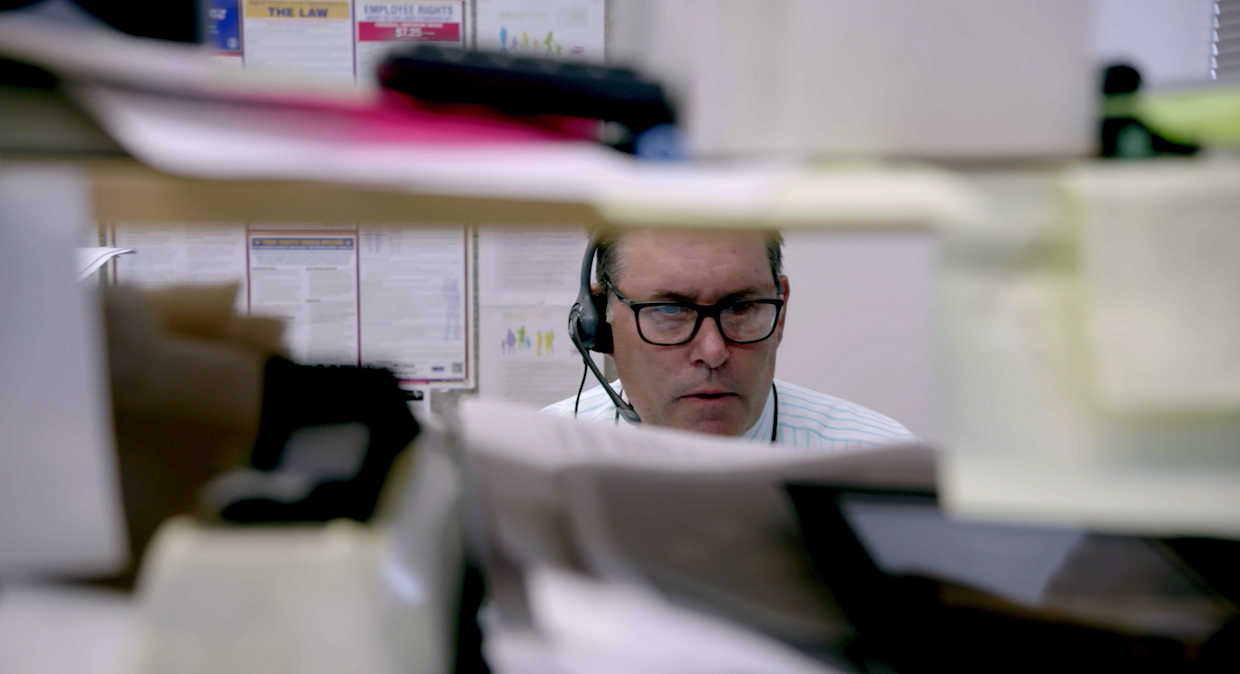

The Panama Papers Alex Winter’s The Panama Papers is a globetrotting, newsroom-hopping peek inside the multinational process, which ultimately brought together over 100 media organizations in 80 countries under the auspices of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ). That led to the 2016 mass publication of documents from the highly secretive, Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca — which in turn brought down heads of state and business leaders the world over, and cost the lives of at least two reporters affiliated with the leaked trove.

I was fortunate enough to catch Winter’s film at this year’s IDFA (in the stunning Tuschinski Theater, no less, which Winter proclaimed the grandest venue any of his films had ever played in), especially because the post-screening chat featured a conversation with not only the director, but also three of the journalists who’d worked on the exposé. (That included Pulitzer Prize winners Bastian Obermayer, whose Munich-based newspaper initially received the tip, and Icelandic journo Jóhannes Kr. Kristjánsson, whose work on the project led to the resignation of his own country’s prime minister.)

Prior to the film’s Epix release on November 26th, Filmmaker spoke with Winter about his logistically challenging, filmed-in-secret film.

Filmmaker: Can you talk a bit about the origin of this production? I notice you’ve got Field of Vision onboard (with Laura Poitras and Charlotte Cook EP’ing).

Winter: I was extremely interested in the story when it broke, because of the size of the leak and its implications, and also because of the unprecedented coordination of so many journalists working together around the world and in secret. It was also clear that despite the significance and scope of the story, it was being suppressed. That motivated me to make the documentary and shine a strong light on both the story itself, and the journalists who broke it. I’d made two short films for Laura Poitras and Charlotte Cook’s Field of Vision and enjoyed that collaboration enormously. So I approached them about being involved. I admire them a great deal artistically and love working with them.

Filmmaker: The journalists you follow seem pretty forthcoming with their blow-by-blow accounts of what went down leading up to the publication of the papers, but I’m also wondering if these reporters set any ground rules for access to them. Did anyone refuse to speak with you, or were certain investigative methods or subjects off limits?

Winter: I spent several months working on research, and reaching out to journalists and people on the inside of the scandal. It was a sensitive operation as, while the main story had broken, it was really just the beginning and many indictments and other consequences were still to come (as they still are). So yes, some people refused to go on camera and some wouldn’t speak at all, but in the end I was very satisfied with those who did participate. And no one set difficult boundaries for discussion, which was appreciated.

Filmmaker: The film retraces the steps these journalists took to publication – that’s not filmed in real time. So why did you have to shoot in secret? And how exactly did you go about doing this?

Winter: The film is a combination of retrospective reporting and real-time documentation. I was only halfway through production when Daphne was assassinated. From the beginning I was well aware that the initial newsbreak of the leak was only the very beginning of a story that would remain active for several years at least. So high security was essential in order to protect my sources, my crew and the ability to complete the film without being obstructed. That required a similar workflow to my prior feature Deep Web: fully encrypted media, encrypted communications, and a press blackout until we were completely done.

Filmmaker: Have you faced any legal — or even ethical — issues with the film? There are stories yet to be published, not to mention people still fighting charges stemming from the revelations.

Winter: We rigorously vet our films, all facts and statements. There’s noting stated in the film that isn’t legally verified. Many of the revelations are quite damning and shocking, reaching across all sides of the political landscape and to the highest levels of power, but the facts are the facts.

Filmmaker: Are you working with the ICIJ on any sort of impact campaign for the film?

Winter: We are presenting the film at festivals around the world with many of the journalists participating in panel discussions. And in addition to a strong TV rollout, we will be getting the film into schools around the world, as we do with all our docs. The ICIJ has a great web-based platform for those interested in digging deeper into this story [which can be found here].