Back to selection

Back to selection

Dispatches from Park City — Tuesday, Jan 29th: The Farewell, American Factory, Luce and More

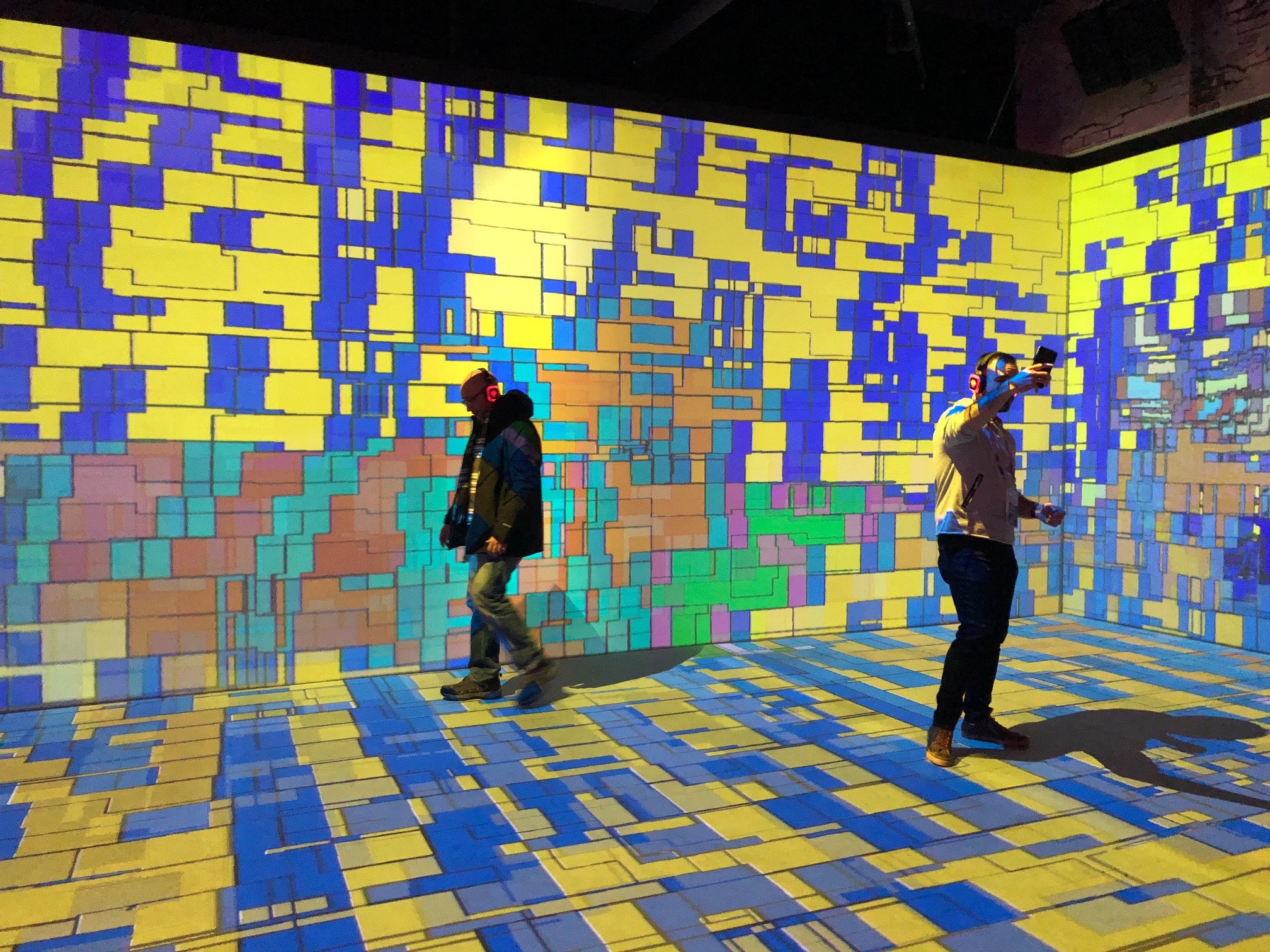

"analmosh", Matt Romein's generative sound and color installation at new 3-sided interactive projection stage @ New Frontier

"analmosh", Matt Romein's generative sound and color installation at new 3-sided interactive projection stage @ New Frontier Welcome to Day Six of Sundance. The $70 parking lot sign has been marked down to $50, the first-weekend scrum of parties is history and Main Street is emptier. Time to get down to serious viewing in the days that remain.

Sundance routinely programs about 120 features. (112 this year.) My personal best—four screenings a day, seven or eight days straight—is about 30 films. The math tells me that I see a quarter of Sundance each year. In other words, no two people see the same Sundance. What follows are notes on films I feel are notable.

Lulu Wang’s The Farewell confirms that Awkwafina’s screen wattage in Crazy Rich Asians wasn’t a fluke. Shot mostly in Beijing, the story has Awkwafina’s lead character, Billi, Beijing-born but scraping by as a young creative in Brooklyn, following her parents to Beijing upon learning her beloved grandmother has been diagnosed with stage 4 lung cancer. The plot revolves around the Chinese practice of not informing the terminally ill of their imminent demise. Instead, Billi’s family (an excellent ensemble cast) concocts a sudden wedding to explain the presence of far-flung family members descending on the grandmother all at once. Despite its terminal premise, the film’s atmosphere is never sad but instead awkward-funny, warm, at times almost joyous. Hip, rebellious Billi alone insists that her grandmother should be told of her condition, and the pushback she encounters leads to a new outlook on the value of traditional practices and family bonds. If properly handled, this film could find a wide audience.

The Farewell unexpectedly introduces a Baroque-inflected score, a high, clear female voice tracing a haunting melody. Similarly, Julius Onah’s Luce is underscored by a portentous Baroque theme played on an organ. I don’t know if this signals a mini-trend, but it’s high time the somber, dramatic pull of Baroque music finds its way into thought-provoking films. It’s a hand-in-glove fit.

Luce is the story of a white couple (Naomi Watts, Tim Roth) living in upscale Virginia, who must come to terms with the fact that their son, a refugee Eritrean boy they adopted a decade earlier (who, it’s implied, was a child soldier), and who now appears to be the equivalent of class valedictorian at his upscale high school, is not the idealized student, all-star athlete, and perfect son they thought he was. Actually, I got all that backwards. Luce is the story of a young Eritrean (Kelvin Harrison Jr.) renamed Luce by his adopted parents, who is suffocating under the expectations placed on him by those who will never—can never—understand him. How Luce navigates this fundamental existential dilemma is the meat of the screenplay, which I believe was adapted from a play. Which may explain why this is one of the most searing, incisive, layered screenplays I’ve seen in years, examining with surgical precision the intersection and inevitable collision of trust, loyalty, hierarchy, family, race, culture, and gender roles. No easy answers are implied or entertained.

Luce’s bête noire (no pun meant) is his school teacher, Harriet, played by Octavia Spencer, in what may be the finest role of her career. This is a staggering performance, more than Oscar-worthy. Harriet’s sister, Rosemary (an incredible Marsha Stephanie Blake), a paranoid schizophrenic who drifts in and out of anger and lucidity, explodes in a scene that would by itself mark this film as unforgettable. But the raw, final confrontation between Luce and Harriet that strips the social and psychological costs of racism in America to its bare bones is beyond devastating and will continue to haunt the audience long after the lights go up.

Speaking of bête noires—A. J. Eaton’s David Crosby: Remember My Name captures inadvertently a portrait of the artist as a young asshole (apologies to Joyce), who somehow survived to be the grizzled ancient asshole we encounter onscreen despite a lifetime of pharmaceutically assaulting his body. Don’t get me wrong, one of the first LPs I ever owned was Crosby, Stills & Nash, and I still treasure the subsequent masterpieces of CSNY. In fact, I was actually at the roadhouse in Houston in August, 1986, when Crosby, shorn of hair and mustache, performed his first night out of prison (which is referenced in the film). I hold his musical contributions in high esteem, but there’s a reason not one significant person in his life, all former bandmates included, with the exception of his current wife, will speak to him. As Graham Nash put it a few years ago, “I’m done. Fuck you. David has ripped the heart out of Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young.” Watching David Crosby: Remember My Name, you’ll glimpse what justifies Nash’s blistering anger after a lifetime of friendship and creative partnership.

For anyone glued to MSNBC or CNN these days, two documentaries about late journalists who were created in their own molds, who each managed to make a dent in the fabric of the universe, will be required viewing. Avi Belkin’s Mike Wallace is Here, made entirely of broadcast clips, is admirably taut and enjoyable simply from a craft perspective, as a paradigm of incisive editing. But it also delivers, unfolding the tightly-wound Wallace in all his inglory, which means depicting his rudeness, fierceness, intensity, audacity, and ultimately, integrity—to thrilling effect. Because Wallace was adamantly private, shielding the very sort of personal information he routinely ferreted from others on camera, the film, try as it might, doesn’t manage to penetrate Wallace’s underlying drives and motivations. It does, however, broach his struggle with depression (if not bipolar disorder), which did impact his functioning if not output. Ultimately what matters about Wallace were his singular achievements in TV journalism, and the astonishing scene in which he flies to Teheran and skewers Ayatollah Khomeini in person is so breathtakingly bold, it’s worth the price of admission. The man had brightly polished brass balls.

Janice Engel’s Raise Hell, The Life and Times of Molly Ivins demonstrates that writer, journalist, and columnist Ivins had solid brass balls, too. A wry Texan humorist in the Mark Twain tradition by way of Smith College, Ivins took no prisoners, gad-flying, muck-raking, pin-pricking, roasting, taunting. and otherwise humiliating, with trademark lacerating humor, hapless state and national politicians who wandered into her gunsights. She famously could outdrink many of the pols she covered in the Texas state house. After being reminded by the likes of Rachel Maddow, certainly one of Ivin’s offspring, and Ivin’s fellow Texan, Dan Rather, of how singularly compelling Ivin’s voice was, all I can say is McConnell and Ryan should thank their lucky stars Ivins passed from the scene from breast cancer in 2007, before their ignoble rise to power (see Peter Principle).

American Factory, directed by Sundance veterans Steve Bognar and Julia Reichert, is by turns entertaining, encouraging, and unsettling. To describe the set-up, I’ll quote the festival’s description: In postindustrial Ohio, a Chinese billionaire opens a new factory in the husk of an abandoned General Motors plant and hires two thousand blue-collar Americans.

There’s no way this can end well, but it doesn’t end in disaster, either. The Chinese managers inevitably run up against Trump-country Americans, with their guns and Jesus subculture, but the Chinese are also myopic and provincial, not to mention nationalistic. Despite this, Bognar and Reichert, to their credit, avoid obvious clichés and seek to show with admirable objectivity the ebbs and flows of East-West cultural exchange, which in and of itself is an endlessly fascinating subject. Some of the Chinese genuinely try to befriend and extend their hand in understanding to the Americans, as do some of the Americans to the Chinese. The irony of Communist bosses opposing and shutting down a union organizing drive is not lost on the filmmakers either. At the end of the day, American Factory depicts two of the world’s political and cultural behemoths converging not in the high-flying realm of international politics or military might, but on the factory floor, through the working class of each country, joined in the effort (or folly, you decide) of profitably manufacturing automobile windshields. Kudos to the score that infuses much of the film’s two hours with hints of Aaron Copland, particularly in the impressive final scene that cuts back and forth between rivers of workers streaming towards the camera, alternating between Americans and Chinese, never quite flowing together.

If you’re a fan of overhead drone shots, now de rigueur for Sundance documentaries, Anthropocene: The Human Epoch is the film for you. The directors are Jennifer Baichwal, Nicolas de Pencier, and Edward Burtynsky, masters of story-telling using what I call god’s POV. Burtynsky made his name with large-format photographs of industrial landscapes while de Pencier is reknown for his aerial cinematography. This Canadian team previously together made Watermark (2013), a look at how water has carved and altered the surface of Earth. Anthropocene examines how humans have done the same, rarely to salutary effect. If a picture is worth a thousand words, this is an entire library shelf, depicting our collective destructive footprint on this fragile planet.

2019 is the 25th anniversary of the founding of Slamdance, the little alt festival that could, which stubbornly still occupies the Treasure Mountain Inn at the top of Park City’s original Main Street.

Like Oskar Matzerath in The Tin Drum, Slamdance refuses to grow up. It has never abandoned its original makeshift, DIY style, nor its two small screening rooms, which convey a rough-edge indie atmosphere long absent from sprawling Sundance with its army of 2,000 volunteers and ubiquitous corporate branding. You could fit Slamdance’s festival staff into one of those frequent Lyft SUVs drifting down Main Street, with enough room left over to squeeze in another rider or two.

This year’s featured graphic says it all: a determined little girl brandishing a Molotov cocktail, evocative of Kristen Visbal’s Fearless Girl facing down Wall Street’s Charging Bull, only flaunting the means to fight back. The illustration is by Mr. Fish (cartoonist Dwayne Booth), subject of a documentary at last year’s Slamdance. Try to imagine Sundance—where my opened jacket and bag are checked by flashlight every time I enter a screening, including press screenings not open to the public—embracing the symbol of a weapon. (As Molly Ivins put it in Raise Hell, The Life and Times of Molly Ivins, and I’m paraphrasing here: You give up liberty for safety, and all you’ve got is less liberty.)

Memphis 69 is one of Slamdance’s major discoveries this year. Imagine a blues concert held in Memphis in 1969, filmed and edited à la Woodstock (which transpired a few months later), featuring blues legends like Furry Lewis, Bukka White, Sleepy John Estes, Nathan Beauregard, Johnny Winter, and Stax Records stars like Rufus Thomas and the Bar-Kays. The Memphis Birthday Blues Festival was organized to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the city’s founding, and coming just a year after the assassination in Memphis of Martin Luther King, appears to have been a local effort to bridge racial divides through music. The audience appears to be made of mostly young, white, aspiring Southern hippies. In other words, a striking cultural time capsule. Director Joe LaMattina explained that a young 20-year-old named Gene Rosenthal organized the shoot, which involved multiple 16mm cameras and Nagras, then sat on the footage for a half century, until LaMattina learned of its existence, obtained the rights, sync’d the footage (mostly by eye, not trivial), then edited the outcome in a “period editing style” for authenticity. If you recognize the names of any of the performers above, this is a must-see.

By the way, Slamdance this year gave its Founder’s Award to one of the festival’s steadfast supporters, Steven Soderbergh. Despite the fact that Sex, Lies, and Videotape, which put Soderbergh on the map, famously made its big splash at Sundance, he subsequently premiered 1996’s experimental Schizopolis at Slamdance and has returned repeatedly since. This year’s edition of Slamdance brings the world premiere of Soderbergh’s High Flying Bird, naturally shot on an iPhone, and the North American premiere of the anticipated Scottish film Beats, which Soderbergh exec-produced.

May Slamdance never reach adulthood.