Back to selection

Back to selection

“Twelve Hours Later and a Few Glasses of Wine to the Good and the Sequence was Finished”: Untouchable Editor Andy Worboys

Untouchable

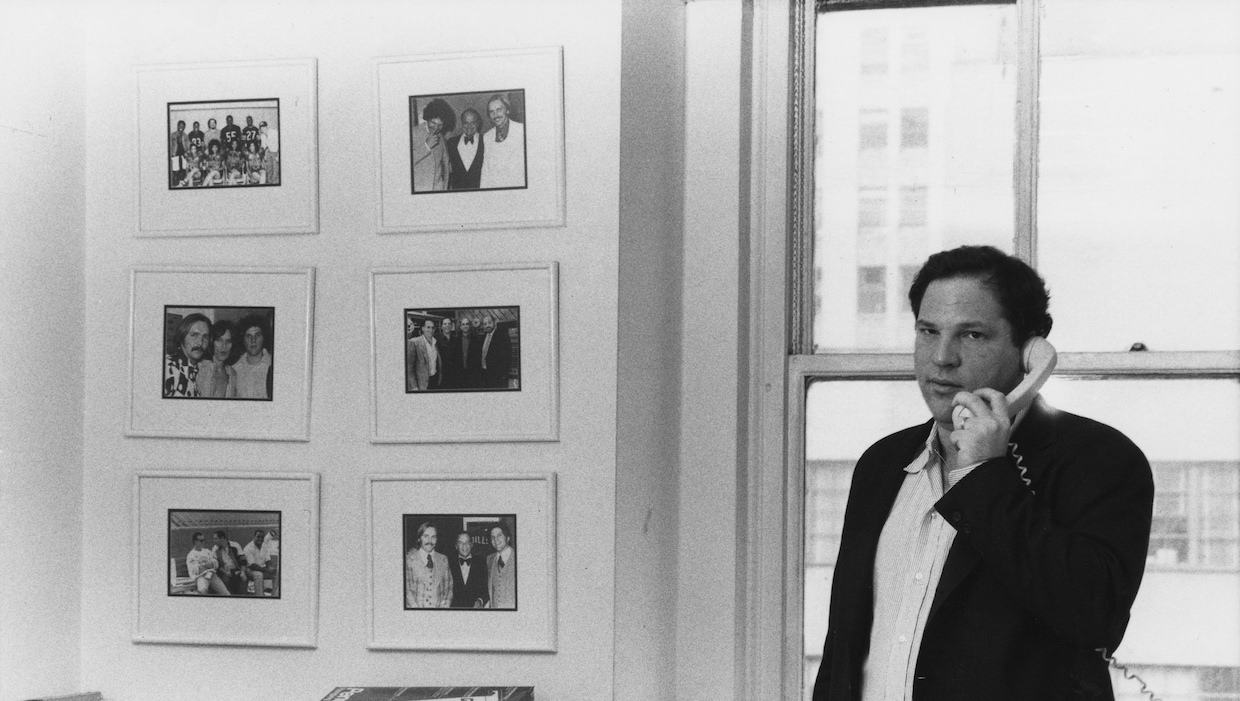

Untouchable The first Harvey Weinstein documentary post-Weinsteingate, Ursula Macfarlane’s Untouchable examines the mogul’s fall through the fresh testimony of many of those he assaulted. Intended first and foremost as a work of journalism, Macfarlane’s film was edited by Andy Worboys, fresh off his work on the TV documentary Hillsborough, a re-examination of the death of 96 people during a 1989 soccer match. Via email, Worboys discussed his work preserving the testimonies of those who spoke on camera for Untouchable.

Filmmaker: How and why did you wind up being the editor of your film? What were the factors and attributes that led to your being hired for this job?

Worboys: I landed the job as editor on Untouchable through fortuitous timing and connections through previous projects. Ursula Macfarlane’s usual editor had a job that clashed which left an opening. Thankfully I knew many of the team from my work on Bart Layton’s The Imposter. Having just won two BAFTAs for my work on Hillsborough, it was enough to convince to meet for a coffee. It all fell into place pretty quickly from there.

Filmmaker: In terms of advancing your film from its earliest assembly to your final cut, what were your goals as an editor? What elements of the film did you want to enhance, or preserve, or tease out or totally reshape?

Worboys: In dealing with a narrative that was and still is unravelling, it was important for us to make a documentary that wasn’t out of date before the film had even been released. It was clear from the raw testimonies that came back from the shoots that that energy within these brave and heartbreaking interviews was key and not to be lost in an overly complicated story. Keeping it simple became the edit mantra.

Filmmaker: How did you achieve these goals? What types of editing techniques, or processes, or feedback screenings allowed this work to occur?

Worboys: Ursula made a choice early on that there would be no dramatic recreations—an easy choice to turn to when there’s zero footage of a story. Two-camera interviews allowed us to create drama and pace in a different way. A key decision was to allow the victims the time to tell their stories of abuse without cutting away from the room. You’re with them: “they can’t leave, so you can’t leave” was the idea. It hopefully adds a visceral layer of uncomfortableness for the viewer.

Filmmaker: How did you achieve these goals? What types of editing techniques, or processes, or feedback screenings allowed this work to occur?

Worboys: Coming from a working class background I often feel like an outsider looking into the industry. It’s an area which has now been recognised and which is slowly improving in the UK, but the industry does tend to live in a bubble and makes films for the fellow bubble dwellers to approve of. So my influences aren’t so much what I’ve seen but where I’m from. I always look at how we can make a story more entertaining and understandable for those outside the bubble.

Filmmaker: What editing system did you use, and why?

Worboys: I’ve almost exclusively used Avid throughout my career. I love the intuitiveness that FCP and Adobe have brought and for shorter formats I often prefer the creative freedom they give you. But with a long format edit that can last a year or more Avid’s more rigid approach to media management is so important to me and my assistants when dealing with hundreds open hundreds of hours of material.

Filmmaker: What was the most difficult scene to cut and why? And how did you do it?

Worboys: We had a structure pretty quickly in the edit, with several characters able to recount their stories without being too heavily cut. However, the director was adamant that we don’t lose any of the contributors who were brave enough to be interviewed. The film was in danger of becoming way too long and losing any intensity we had created. We decided to make a virtue of the fact that many of the stories overlapped and would be enhanced by trying to tell them all together. I went into the edit one Saturday when I knew there would be no one around and the phone wouldn’t ring. Twelve hours later and a few glasses of wine to the good and the sequence was finished. It’s a sequence that barely changed from first cut to the film’s completion.

Filmmaker: Finally, now that the process is over, what new meanings has the film taken on for you? What did you discover in the footage that you might not have seen initially, and how does your final understanding of the film differ from the understanding that you began with?

Worboys: I feel very lucky to have worked with a director and team that had a very clear idea of the film they were trying to make. No matter how many times you read these stories in print, you’re still not quite prepared for the emotional journey you go on in the edit when contributors reveal their stories. It’s always a privelage to help tell their stories which can help change perspectives and hopefully inspire others to speak.