Back to selection

Back to selection

Moonshot: Todd Douglas Miller on Apollo 11

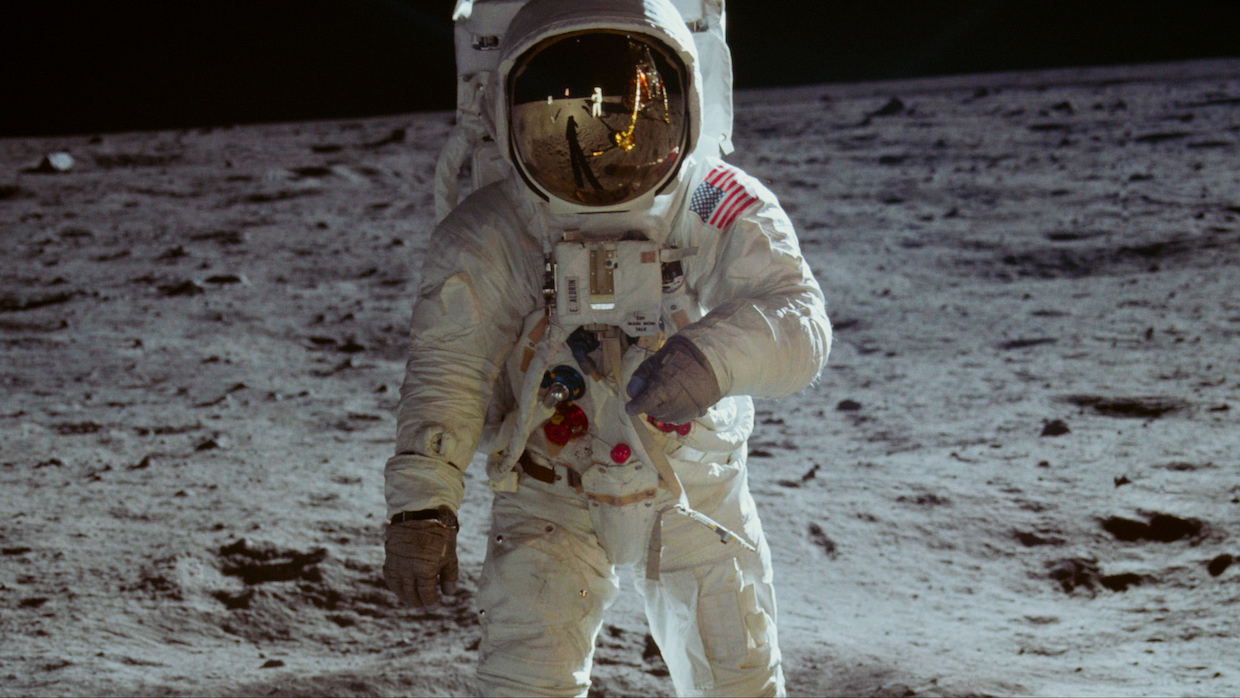

Apollo 11 (courtesy of Neon/CNN Films)

Apollo 11 (courtesy of Neon/CNN Films) Todd Douglas Miller’s Apollo 11, which premiered at this year’s Sundance, originated from the simple idea of using archival footage to revisit, in time for its 50th anniversary, the first moon landing. For those who’ve grown up watching the same images trotted out over and over—Neil Armstrong bouncing on the moon, a burning ring of fire propelling itself backwards toward Earth as Apollo leaves the planet—the premise seems tedious and redundant, an ossified staple of Baby Boomer montages regularly intercut alongside clips of Woodstock and the Vietnam War, now freshly recharged by nationalistic rumblings about a space force. And as far as feature documentaries go, this ground was covered 30 years ago, when it was only the landing’s 20th anniversary, in Al Reinert’s For All Mankind. What else could there be to see? As the archival assembly of Apollo 11 demonstrates, plenty.

Miller premiered his previous documentary, 2014’s Dinosaur 13, at Sundance after a break from feature filmmaking. During this time, he’d started a production company, Statement Pictures, and was working on a short for CNN about the final moon mission, Apollo 17. That project coincided with the rediscovery of a trove of 70mm Apollo 11 footage, the bulk of it previously unseen by the public, that had been shot during the mission. The footage had once rested in NASA’s storage facilities, and while some of it had been used (albeit cropped from widescreen to a 4:3 ratio) by Theo Kamecke’s 1970 documentary Moonwalk One, the bulk had been relocated into the National Archives’ vaults, unseen and semi-forgotten. At the same time, thousands of hours of audio recorded on 30-track recorders from Mission Control had been sorted through by Stephen Slater, a 31-year-old independent archivist whose labor of love was to try to sync this audio (recently digitized by engineers at UT Dallas) with silent mission footage.

Edited and directed by Miller, Apollo 11 begins in the immediate hours before liftoff, as the rocket is towed out toward the landing pad. The massive visual scale of the enterprise is restored, the sound all-encompassing, reawakening a whole dimension of spectacle that’s been removed through overfamiliarity. In montages crafted from newspaper headlines and stills, Miller tersely fills in the backgrounds of the three astronauts—Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and the perpetually underrecognized Michael Collins—but focuses on the experiential aspects of the event rather than the psychology. (For those haunted by recent footage of Aldrin standing behind President Donald J. Trump and barely keeping his face from collapsing into disgust during a recent press conference about Making NASA Great Again, the footage of Nixon calling and congratulating the crew on their accomplishment is a useful reminder that perhaps not much has changed, merely worsened in the same ideological direction.) Talking heads are not an option; graphics are limited to a single recurring illustration of the spacecraft’s trajectory to the moon and back.

Made with the help of NASA and the National Archives, Apollo 11 evolved from just a documentary into a full archival digitization project that’s also an unusual example of an American public–private partnership, in which the corporate monies used to restore and freshly digitize footage on a variety of formats serves the public end of preserving the footage for future citizens. A Midwesterner who now lives in Brooklyn, Miller spoke about the considerable archival challenges of assembling Apollo 11, now in release from Neon/CNN Films.

Filmmaker: I looked at your IMDb resume this morning, which specifies that your first film, from 2001, had a $12,000 budget. I don’t know where that number came from.

Miller: I didn’t even know that was on there.

Filmmaker: After that there’s a narrative film, then a gap during which you started a company that works on short films, archival, IMAX. You came back around to features with Dinosaur 13 and now this. So, your entire production model has changed, and you assimilated a lot of skills working with archival and large format over the years. Can you talk about that trajectory?

Miller: The first documentary I did was Gahanna Bill. It started in film school, at the Motion Picture Institute, outside of Detroit. I went to Eastern Michigan University, and it was a lot of film theory. We’re talking about the late 1990s, the last century. They shut down the production department, got rid of all the Bolexes, Rex 16s. There were a couple of filmmakers, local guys who worked with Sam Raimi, one of whom was Douglas Schulze, who opened up a training school. It was one of the few, back before there were a million of them, and it was great because they had all new equipment, new lights, new cameras. We were shooting on 16 at the time, and had a bunch of Arri S’s. Gahanna Bill started on 16, [then] we shot a little 35. I followed a middle-aged, mentally handicapped guy in Columbus, Ohio, the town I’d grown up in, for about four years. He was kind of the town mascot, and it became this community inclusion piece. We went from a somewhat big film school–esque crew to everybody wearing every hat. By the time I’d finished, the VariCam had come out [and] the Sony CineAlta, so we were finishing on video and digital with some of the first big boy cameras. Long story short, it was a good little film to learn how to make movies on.

I really wanted to be in narrative, so my next film was Scaring the Fish. We shot it in six days in upstate New York, from a script that we’d gotten through a theater company, MCC, written by Ben Bettenbender. We wanted to shoot it with two cameras and just go, so we shot very quickly, like 20 pages a day. It was a fun thing and really didn’t go anywhere. We just did it as an experiment to see if we could do it. And then, I always have to eat, so I’ve been doing freelance directing and producing gigs along the way for years. I’ve done stints at various production companies where they have large format films [and] shot large format digital for a lot of corporations. Being in and around Detroit, there was a lot of car shooting that went on, both on film and in large format, so I was always exposed to that side of the industry.

Dinosaur 13 was an attempt to make an art film about paleontology that evolved into following one particular paleontologist’s story. Plus, it was a great excuse to get out of New York City for a while and live out of a tent in the Badlands of South Dakota and Wyoming. After Dinosaur 13, we were approached by a lot of people to do things. I’ve had Statement Pictures with my producing partner, Tom Petersen, for a while now. We really like doing our own thing; we’re quality over quantity kind of people, so we knew our next project was going to take years. At the same time as I was working on Dinosaur 13, I had a couple of other space-related projects. One was a CNN short film called The Last Steps [about the Apollo 17 mission]. And we were working on another space-related documentary, but we needed to let the story play out, so it was going to take years. Doing that film, we needed to find the provenance of one particular moon rock collected on Apollo 17, the last mission to the moon. That gave us an entry into the archive system with NASA, the National Archives, and also I was introduced to archive producers and archivists.

In the time we were working on that film, CNN had approached us: “Hey, if you want to do any short, any idea you want, we’d be interested.” And we came up with this idea to do Last Steps, just because we were exposed to this wonderful archive. The archive producer I was working with out of the U.K., Stephen Slater, had done all the synced sound stuff with 17. So, once we finished that, he goes, “Look, I’ve got a ton of stuff synced for 11.” I initially said “No, I’m done with space because I’ve been doing it for a couple of years,” but I looked at a lot of his stuff. After seeing some of the things that we could use to supplement his synced project, I realized that there hadn’t been a major effort to rescan any of the original materials, whether they were ground based or space related, in more than a decade. That’s how the project really started.

Filmmaker: As an editor, I don’t know that you’d ever had to work with this much archival footage at one time.

Miller: No, not at all.

Filmmaker: So when you got started organizationally, how did you do it? Did you let somebody else watch all the footage and log it? Did you watch it all and log it yourself?

Miller: There’s only one way to do it, and that’s do it all yourself. We did that for the short film. It wasn’t as intense as it was on this, but we had to create timelines for every single day of the mission. One of the rules that we had, rules I put upon myself, really, was I didn’t want to see—I always hated watching space films where, if you see guys in mission control, it was always generic cutaway shots. You would see a guy in a blue shirt in one edit. Two seconds later, he’s in a white shirt from three days later, and he hasn’t shaved.

Stephen had started syncing up all this mission control stuff into days and locked it on, basically, a 24-hour timeline. [The goal] was to look exactly minute by minute, frame by frame, [at] what was happening. For the first few Apollo missions, it was all MOS. So, if you got lucky, the cameraman would pan to, like, a clock in a room, and then you could match it. But for the most part, it was all just listening, knowing what was going on in the mission, and then trying to lip sync it all. It was nearly impossible at first, but as the months went along we chipped away at it. [Stephen] did the lion’s share of all of that. So, by the time I had started editing, we pretty much had all the mission control stuff down. But it’s pretty boring, you know? So, it was more about filling the gaps and what were the big moments in the mission. Simultaneous to when we were discovering the footage, this audio got dropped in our lap through NASA. That was 11,000 hours for Apollo 11, and we did a divide-and-conquer approach. The goal was to identify things that were interesting, [to see] if we could use them supplementally with all the major things, and if there was anything new. So, we would be walking to work, Tom, my producing partner, and I. We threw that 11,000 hours on our iPhones and listened to it literally around the clock until we found something good.

Filmmaker: The custom scanner built to get the footage re-scanned, did you get involved on the tech side of that?

Miller: Yeah. Initially, the idea was to re-scan all the 16 and 35 millimeter.

Filmmaker: The 16 and 35 were coming from what? 35 is once they’re actually out in space?

Miller: [That’s] all 16. There was very [little] 35. A lot of the 35 was traditional 35, Academy formatted, in and around the launch pad. All the 35 was ground based. The only thing they took into space was a digital acquisition camera, custom built by Westinghouse, that was 16 millimeter. And for 11, it wasn’t their mission to actually capture anything. They did have a couple of Hasselblads, 70-millimeter 4×5 medium format cameras—beautiful, beautiful imagery. All the other missions, they were trying to document what they were doing. 10 had paved the way; they documented the hell out of that. With 11, their goal was to just get there, land and take off, so a lot of the documentation was secondary. Having said that, with the Hasselblad imagery, there were 1,025 still images spread across seven different magazines, so that’s a lot to work with. I knew that no one had utilized those [in a movie] in a really innovative way. I’d go down to the Museum of Natural History, to the Rose Planetarium, [and] they have it plastered all over the planetarium’s walls. They’re gorgeous, in this incredible 70-millimeter medium format. So, I knew that that would be a central part of what we would use once we were on the lunar surface. They also used those cameras inside the capsule and inside the lunar module.

Getting back to the 16 footage—it’s one of the most documented events as far as launches go. We had access to all the 16 millimeter and a ton of 35. All of the stuff in mission control, that was primarily two cameramen, “Bird” and this other guy, “Bear.” They both had two 16 cameras apiece. Sometimes, they would throw down and shoot 200-, 400-foot daylight spools, and it was very quick—they would throw a camera down, pick up another one, rifle off a couple of shots if somebody was talking, put that camera down, grab another one so they wouldn’t have to change mags. It was very chaotic to get through from an editing standpoint because once the rushes were put together, they were all over the map. So we had stuff from, like, day three that was combined with day one, stuff from day seven combined with day two. That was really tough to get through.

The initial idea was to scan all of this 16 and 35 at 4K. We had a 4K scanner, one of the fastest that had been manufactured, made by a company called Digital Vision. Our post house, Final Frame here in New York, had a very close relationship with them, so we felt really good about that workflow. We got in a meeting at Final Frame with the National Archives and government people. And the owner of the company, Will [Cox], who’s my colorist—I’ve known him for years—said, “You know, if we wait six months, we can do 16K.” And I went, “Oh god.” I’d known from being a student of large format what that meant. At the time, we had discovered the 65 five-perf stuff, and we also had 70-millimeter 10-perf military-grade engineering film, which is all the great close-up stuff of the rocket taking off. So we knew we had that, but to wait six months, from an editing standpoint, was going to be pretty tough. Everybody looked at me, and I just laughed. And I said, “Well, you only get one shot at this. What the hell.”

So, we waited six months. That turned into eight. At one point, Final Frame looked like the back room of one of those car shows that you see on cable. There were pieces of things everywhere, and we had two scanners, a 4K and an 8K, going at one time. One was to service the other one, really. The way the scanners work is, on one scanner you have a camera that’s looking down, and then you have a separate camera that’s looking [horizontally] making sure all the perfs are aligned properly—basically looking at the film and making sure it’s going through the scanner properly. The cool thing about this particular scanner was, the actual plates were interchangeable. So, depending on the different gauges of film, it could do all the way from 8 millimeter up to 70 millimeter. So, we knew that we’d have to get into machining plates if we didn’t have them. There were just so many different flavors of film we were throwing at it that we knew things would break. At some points, there were screws that would come off, and everything’s custom. So it helped to have a second [scanner] there. Important to note [that] with the audio, it was very similar. NASA [did] what’s been called the 30-track historical voice recordings, which was 11,000 hours. They had one machine built that was capable of recording that back in the ’60s, and they had another machine that was created just to service that one in case it broke down. So, it was a very similar setup. If you’re doing anything with prototypes, it always helps to have two. It’s like that scene in Contact when they build the alien blueprints: “We built two. One’s in a secret location.” We had one hardware guy and one software guy literally working around the clock for a few months at Final Frame, handwriting code and getting the sensors and camera systems to work. We were machining parts here in Manhattan to make the plates work because all of the different large formats there; every reel we got was a little different, so we would have to make sure that the plates themselves could fit the film.

Unlike a lot of the other scanners in existence, this wasn’t pen registered, so at no point were there any moving parts actually touching the film negative. It rode on a cushion of air the entire time, so it was very tough to get that pressure right depending on what part of the reel you were on. A lot of this footage hadn’t been touched, a lot of it was B-wound, so we had a lot of technical obstacles with it. Once we got into testing some of the footage, we found that there really wasn’t a need with the 65 five to go any higher than 8K. There was a diminishing return, which greatly affected our workflow. I believe the numbers were like, instead of having a terabyte a minute, we went down to 500 gigs, something like that. So, we knew we could scan it. The next thing was workflow storage. We were looking at, or close to about, a petabyte at 8K with all the footage. But surprisingly, there’s not a ton. It’s approaching 30 hours on the large format side of things. The 16 and the 35, re-scanning all of that—again, initially, we were going to do it all in 2K, but we actually found that there was some more information to be gained. So, we ended up scanning it in 4K.

Filmmaker: What is the difference when re-scanning?

Miller: It depended on the reel and how it was shot. We would scan it first, then throw it up on a big screen and look at it with really expensive laser analysis and see if there was any more information to be gained in the pixel counts. Nine times out of 10, there was, so we would go back and re-scan it at a higher value. We did that also with the 8K. It’s almost the equivalent of an HDR process. One of the biggest discoveries was, there were actually 65-millimeter cameras in mission control. A lot of it was shot at varying frame rates—12, 18 frames per second, so it looks like Babe Ruth hitting a home run and running around the bases. We had to do a lot of time remaps with that because it was so underexposed. We think that they were exposing via frame rate on a lot of the shots. Possibly, it was too dark. Maybe they screwed up. We don’t know—unfortunately the cameramen aren’t around anymore—but the footage itself needed to be scanned at different values. We did color passes on some of the shots, then blended them together and made them look as good as they possibly could. It’s a very, very long process. The 8K prototype scanner? There’s only one in existence. It’s pretty cool, and it was made for this project.

Filmmaker: I think your only graphic is the line that shows Apollo 11’s trajectory. I don’t know if that was violating a rule, if originally you didn’t want to have any graphics in there.

Miller: Having made a dinosaur movie, I thought that that world was very cutthroat. It’s nothing compared to the space community—and I’m an honorary member. One of the first people I approached before we even did the short film was Al Reinert, who had made For All Mankind. I called him because I thought at the time no one had done a better staging sequence than what I watched in For All Mankind. And I wanted to ask his permission to use that because I just thought it was so cool. There’s not a lot to choose from when it comes to staging, [which is when] the rocket, after it launches, separates—the first, second and third stage. The way everybody always usually does that is it’s this big POW, explosive bolts that go off. But in space, you don’t really hear that. Al just had this beautiful, poetic shot inside. It was taken with a 16-millimeter engineering camera on one of the unmanned crafts. It was one of the most famous shots in space history. The camera actually ejected itself, became its own capsule, had its own parachute, went into the ocean and was collected by NASA. Which, in and of itself, deserves a documentary.

Al and I hit it off and talked a lot over the years. I knew that he had gotten flack on For All Mankind for compositing different missions and making it [look] like one mission. I personally don’t have a problem with that, and I let him know I think his film’s a masterpiece. But I asked him: “When we make this, I need to do that because I’ve talked to the astronauts, and I want to convey what they experienced. And the only way to do that is by taking things from other missions or graphical support and reinforcement.” Unfortunately, Al just recently passed away

When it came time to do 11, I knew that there were scenes in there that no one had ever put on film. [When] they light the fire to actually go to the moon after they’ve been in orbit for a couple of revolutions around the earth—all the astronauts write about it. It usually happens on the dark side of the earth. Neil Armstrong was interviewed during the 40th anniversary, and he was asked, “What was your most idyllic moment of the mission?” It wasn’t setting foot on the moon, it wasn’t landing safely, it wasn’t even getting back to earth. It was when they were coming up on the moon and they saw, basically, a solar eclipse of the moon. There was just a circle, and the moon almost looked 3D. The sun is coming up over the earth, and they’re just going into it. They call it the terminator. They go through the terminator and are on their way to the moon. I’d never seen that depicted in either a doc or a fiction film. We had a really good view of that, taken from another mission, that I knew I was going to use. I’d shown it to Mike Collins and to Buzz Aldrin and said, “Is this what it looked like?” “Yes, that’s exactly what it looked like.”

We owe a lot to the film Moonwalk One, which has become a cult classic that I can go on and on about. They had this cel animation, and I was always a huge fan of it. It simplified everything [about] what the spacecraft was doing. Initially, I’d used that in the edit, but after we started working with NASA’s history department, we knew a lot of the things were wrong, like the orientation of the spacecraft. We had to look at the data and the telemetry that was recorded. Once we [revised and] showed it to [the astronauts] they were like, “Oh yeah, that’s exactly what had happened.” So, what ended up in the film were simple animations that I created to show these guys. The original idea was to make them more modern and 3D. We did some tests with that, but it just looked too glossy. It didn’t look like it belonged. So we went back to our shitty little cel animations. And now I love them, and it’s something space nerds that have been consulting on the film like, and my mom can like as well.

Filmmaker: It was interesting to me that the first press screening of your film here was at a multiplex. You never hear the words, “We are only screening this documentary in the largest format possible.” This is extremely unusual territory for a non-IMAX-oriented documentary. I know there is this IMAX version that’s coming out. But at what point did you commit to demanding the best quality projection for a nonfiction project?

Miller: Everybody forgets the footage was shot by these amazing cinematographers. The astronauts, they’re ASC members. One of my favorite pieces of film ever shot was by Michael Collins, who just happens to be an astronaut, but he flipped the 16 millimeter camera when the lunar module was coming off of the moon surface. We show it in the film as an unbroken shot, and it’s one of my favorite shots of all time. The same thing with the landing. That was Buzz Aldrin shooting out the right window. He forgot to turn on the camera on the lunar ascent, he turned it on six seconds after. But for the landing—I thought it’s one of the most historic pieces of cinematography ever shot. The same goes with these great cinematographers who were shooting all this ground-based stuff during launch and recovery. One guy, they called him the Bear—unfortunately he died in ’74 but a tremendous guy. He was handholding these giant Mitchell 65 five-perf cameras. Right off the scanner, it looked amazing.

We had always envisioned there being a science center and museum version of this, which would’ve been under an hour, about 40 minutes, that would play long-term at places. Neon came on board as theatrical distributor and walked it in the door on the commercial side at IMAX. But I can tell you, working with the IMAX team, some of whom I knew from earlier stuff, they’re absolutely phenomenal. I just got back from there the other day. We were doing the DI on the Xenon version, which is 2K, and the laser 4K. I encourage anyone who’s going to go watch this, watch it [projected from] a 4K laser. It’s absolutely spectacular and 12-channel audio. We went to a lot of expense. The work Eric Milano did on the sound mix—usually you have 12 guys work on this stuff. We worked on it so long that Eric did everything himself—all the foley, everything.

Filmmaker: What were the rules for foley in terms of reconstructing atmosphere, especially within mission control? Obviously, you had to construct some of that. I’m not sure if you could only draw upon archival or if you were going to put a little library tone in there or what.

Miller: Our rule was, if we didn’t have reference for it, we weren’t going to create it. We were very fortunate early on. Although we were flying under the radar, the space community knew about us, so a lot of the older engineers that were around during the Apollo days were giving us materials from everywhere—cassette tapes, 8-millimeter recordings from the launch that day that were poorly recorded, just because of the limitations of the time, but they were great for reference. So, if we had a helicopter, for instance, we needed to know the exact helicopter sounds. So we went and grabbed that. Luckily, the Smithsonian has been a great partner on the film. The IMAX at National Air and Space in [Washington,] D.C., we used that as our testing theater.

I always wanted to know exactly what the sound of the Saturn V rocket sounded like. I drove the team nuts, I’m sure, but we needed to nail it. It’s just not a low sound. There’s this high popcorn sound that happens, and everybody talks about. You could hear it through some of the TV broadcasts, but we found actual recordings. I wanted to know what it sounded like in every single space: What did it sound like two miles away? What did it sound like when you were in the VIP stand? And what’d it sound like when you were in a helicopter, because we had shots of it taking off from a helicopter? All those things combined were the guidelines that we gave Eric. It was basically all him. Sounds in mission control, sounds in the firing room, we needed to know what those computers sounded like. Those analog computers and IBMs, we got them and integrated them into the film. There’s a shot in there—everybody thinks it’s a dolly shot. That was Theo Kamecke, the director of Moonwalk One, who was the only civilian in the firing room. He actually used a wheelchair as a dolly. So, we wanted to hear the sound of the wheelchair. What did a wheelchair sound like back then? Well, let’s get a ’60s wheelchair.

I can’t tell you the sleepless nights, the nervousness and anxiety [that comes with] having priceless reels that haven’t seen the light of day trucked up to New York from D.C. in climate-controlled vehicles, and having our team work with those materials. It wasn’t until they were all safely back, which was months and months of work, that we could sleep at night. But I had always said to everyone at both NASA and the National Archives, “You’re not going to get a better team that’s going to care more about these materials.” Forget about the film itself, just the materials. We always felt a real duty to curate and preserve these properly, and to digitize them in a way that was emblematic of the way in which they were cared for for the last 50 years. These reels weren’t misplaced. They weren’t thrown to the side. I joke they were next to the Ark of the Covenant in the National Archives facility, but the truth is that no one really had a way to economically deal with these materials. Back when Moonwalk One was working with them, there were contact prints made from 70 and 35 here and down at Cape Canaveral, Technicolor. And that was it. The originals just got put away because who’s ever going to want to work with that? So, we knew what we were working with. We knew the responsibility. And we’re still working with that material, too, trying to get it back into the system, which is years of work. It’s just not Apollo 11. It’s everything that precedes it and everything that came after it.