Back to selection

Back to selection

“We Make the Films We Can Make, Not the Ones We Want to Make”: Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Qumra Masterclass

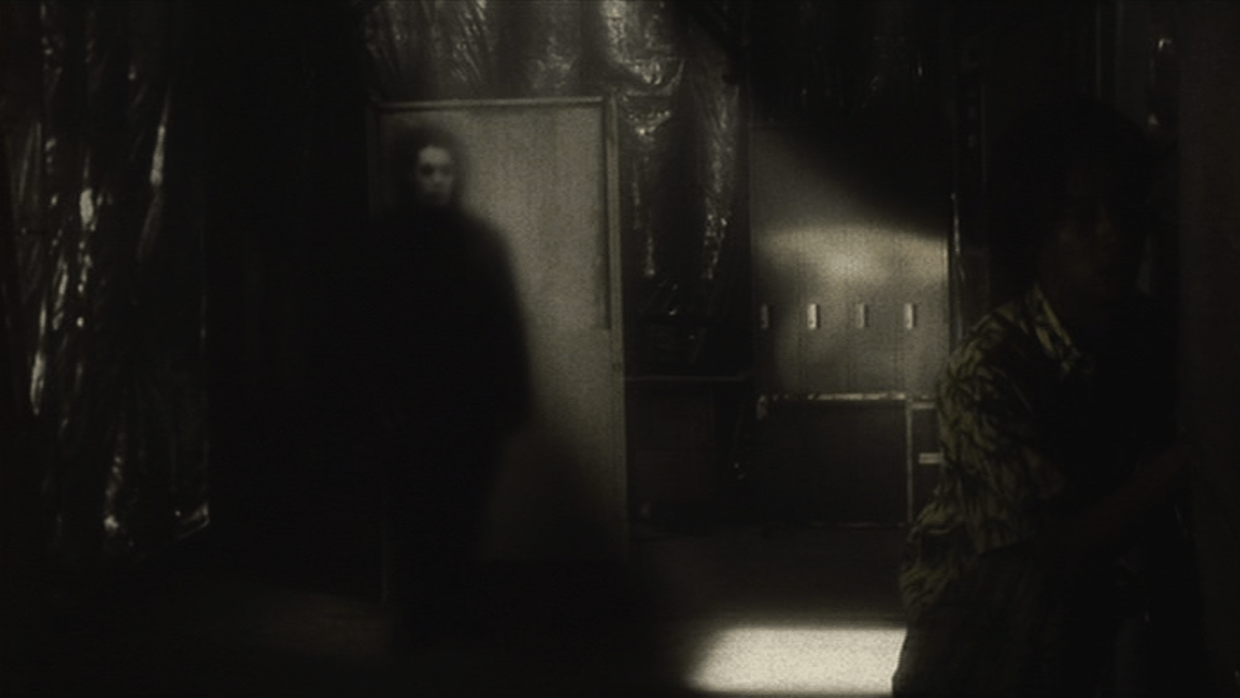

Pulse

Pulse An initiative of the Doha Film Institute, Qumra is an event that connects Qatari and international directors who are receiving different stages of DFI-funded support with industry delegates from across the spectrum of the film world and master filmmakers who meet with emerging talents and engage in public conversations. The 5thedition took place between March 15thand 20th, 2019.

Kiyoshi Kurosawa is known best as a horror filmmaker but the prolific director has effortlessly moved between different genres—his latest, To the Ends of the Earth, a drama expected to play Cannes, is about a young woman shooting a travel show in Uzbekistan. One of the most notable departures was family drama Tokyo Sonata, the film selected to screen in Doha the evening before his masterclass as part of the 5thedition of Qumra. French film critic and historian Jean-Michel Frodon introduced the screening by saying the film is known as a “non-ghost movie” by a “ghost movie director” when in fact he takes issue with both claims. Tokyo Sonata “has ghosts, they’re just hidden better,” and Kurosawa is far more than a “ghost movie director.” Indeed, Tokyo Sonata is as eccentric as any movie he has made and, in its own way, veers toward the supernatural and spiritual. Likewise, in spite of Kurosawa’s demarcated skills at building horror and suspense, his formal choices with less sensational material can be just as, if not more, inspired.

Building on this observation, Frodon led his masterclass into a direction that focused on breaking down specific scenes in detail and trying to tap into Kurosawa’s motivations and line of thought. Regrettably, much of the two hours allotted for discussion were eaten up by translation, and the nuances of Frodon’s questioning were often lost amongst it. One could imagine the two of them continuing the conversation for hours, maybe even days, in a more Hitchcock/Truffaut-esque way.

Before diving into clips, Kurosawa described the turning point of his entry into filmmaking when he met Japanese film critic Shigehiko Hasumi: “it changed my life.” Studying under him at Rikkyo University, he learned that cinema was far more than he first thought. It was also then that he got to experiment with Super 8 cameras. which taught him the importance of craft and precision: “I was blessed to start with Super 8, because it’s such a hard process to make. You just see this small square and it challenges you to translate what you see in front of you. You see a reality in front of you and filmmaking is adding these realities together and creating a special reality.”

From there, Kurosawa started out professionally making Pinku eiga and V-Cinema (Japanese DTV) films, where he developed expertise in genre before breaking out internationally in 1997 with Cure, a film he had been thinking about “for 10 years.” He cites the strong influence of American genre films of the 1940s and ’50s: “That’s how I learned how to work with low resources. The hardest part is when nothing is happening but you need to make the audience feel like something could happen…those Hollywood films taught me how.” At this point he acknowledged Frodon, who praised Cure when it premiered: “he told everybody there was a weird Japanese movie out and it helped my career immensely… Speaking of my career, I realize it was built not because of intentions but because of circumstances and people’s help and influence.”

Looking at the opening scene of Pulse (2001), a film born from Kurosawa’s time as part of a residency at Sundance, which follows a young woman on a sunny day as she walks along the street and up to an apartment, Frodon dug into the formal elements that build suspense—lateral tracking shots and intense music before she enters the apartment, the ingenious use of space (including a translucent sheet that divides a room used to considerable effect) and perspective once she’s inside and encounters a troubled man—but this is where the translation failed to allow a focused discussion. “The shoot took a day from sunrise to sunset,” Kurosawa explained. “We prepared a lot. The opening scene is the most important for setting the tone and creating the anticipation the audience feels.” Describing one mysteriously blurred, manipulated shot from the scene, he revealed that he “wondered what it would look like from the ghost’s point-of-view.”

The masterclass couldn’t accommodate a proper overview of his career and from there they only touched on two more sequences, one from Bright Future (2003) and one from Journey to the Shore (2015). In the former, Frodon selected an expository scene that introduces a key male character in conversation with a woman and is mostly shot in a static long take. “I chose the location because of the angle of the camera I wanted. The woman walks around, even out of frame, but we stay on him,” Kurosawa said. For Journey to the Shore, the scene choice surprised Kurosawa: “I didn’t think you would choose this scene!” In it, a man is giving a lecture on the science of light to a room full of people: “I thought about the character’s lecture and wanted to use natural light for the scene and to capture the movement of sunlight as he speaks.” Frodon’s choice of excerpts nevertheless proved illustrative of the variation and purpose of technique in building sequences and moods in Kurosawa’s work.

When questions opened up to the audience, he offered some advice to fellow filmmakers. “You don’t always get to make the movie you want,” he said, advising filmmakers to take on different projects and allow their career to go in different directions and to trust the influence of trustworthy people around them. “Films are not an individual process, they are collaborative. More often we make the films we can make, not the ones we want to make. If we’re lucky, once in a while the creative process transforms it into the film that you want to make.”