Back to selection

Back to selection

All We Have Is Now: Borscht 0 (2019)

My First Film

My First Film “Essentially, cinema is dead, and this fellowship is bringing it back to life,” went part of the on-stage intro for the showcase screening at this year’s Borscht. “The people that most of you know are old, and we’re young, and I think we’re more exciting.” At the screenings I attended, Borscht co-founders Lucas Leyva and Jillian Meyer repeatedly, shamefacedly noted that they’d started the festival (and attendant collective of the same name, the screening of whose work is the fest’s top priority) with the intent of never showing the films of anyone over 30—only to, alas, themselves cross that decade line. (Beats the inevitable, as they say.) Implicit in the festival/organization’s work is a thesis that it’s important to engage with the present, even (perhaps especially) if that present is actively unpleasant, and the shortest path to understanding the Now is through the youth, who will shape the world’s idealistic future rather than growing up to be our latest generation of ruling class evil old men.

I don’t object to these statements on a general basis — “kill the old, we’re the new artists in town” is a totally understandable rite of passage everyone should have access to if they want it. Going in, my general feeling — as someone who’s spent vast portions of my life trying to pretend that being a Luddite is a real option — was that it’s probably healthy for me to get over that impulse every now and then and see what’s out there, even if it’s not for me. The night before the big showcase screening, “Bisquetopia” was an evening spotlighting even younger filmmakers affiliated with Borscht. Instagram-ratio animation, social media scrolling rendered in real time, ’80s title fonts and the kind of head-mounted GoPro distortions of space long normalized in online videos were all accounted for.

One short (for which, infuriatingly, I cannot find a director name or title on the printed-out fest program) concerned the “cheesed challenge,” exactly the kind of viral flashpoint I spend my life consciously evading. In March of last year, there was a brief wave of parents throwing sliced American cheese packets at their infants, which led to articles with unspeakable headlines like “The cheese challenge: why people need to stop throwing cheese slices at babies’ faces.” The short takes things slightly further: a young man repeatedly tries to get his adult headphones — wearing co-worker’s attention so he can cheese him, and when he finally succeeds the dude is not impressed. Why would you do that, he demands to know? Because it’s trending on YouTube, the anti-comic protagonist (?) replies. “But I don’t care what’s trending on YouTube,” is the response (paraphrased from memory), which captured a certain kind of exhaustion I can roll with and will be a personal go-to punchline that’s not really a joke. I didn’t know this was based on a real thing until someone told me, and by looking it up after the screening I have a new piece of knowledge that my mental-garbage-hoarder tendencies will never, ever allow me to unlearn. Do I now understand the present better in a meaningful way?

Early in the showcase program, I was reminded that the kind of really out-there conspiracy mongering that was quietly bubbling under, confined (seemingly safely, although this turned out to not be true) during my childhood to AM radio, Loompanics publications and primitively formatted message boards is now, unavoidably and possibly irrevocably, part of the Mainstream Cultural Conversation. Part of Borscht 0’s showcase night, Brad Abrahams’s Conspiracy Cruise reminded me of this cruel fact, refracting this ongoing nightmare through an Adult Swim-friendly sensibility. It didn’t surprise me to learn that the short is “meant as a proof-of-concept for a feature or miniseries,” or that its star, Henry Zebrowski, anchors an actual Adult Swim show, Your Pretty Face is Going to Hell. The age gap is not a factor here, as all the involved appear to be in my age bracket, I’m just not the target market for joking about e.g. the kind of mental illness that brings believers in Reptilian Shapeshifters into the same (metaphorical/literal) room as libertarian wonks convinced abolishing the income tax is the only path to their Randian future.

On the other hand, I did find Dylan Redford’s Emergency Action Plan (E.A.P.) grimly funny. Here, the Borscht stalwart (and, yes, Redford grandson) dives right into worrying about mass shootings, relating his train of thought in a breathless voiceover. Clips from many, many instructional videos on How To Survive A Mass Shooting fill out his train of thought, and these are bracing indeed — industrial-video recreations of shootings, with all kinds of clunky choices made in choosing how to depict this event. The hilarity of bad actors, playing both shooters and victors, trying to sensitively/realistically render sheer terror and panic, is real, even as it’s mitigated by the very unfunny reasoning (necessity?) behind the sheer quantity of this new instructional film sub-genre.

I was new to Borscht, able to learn abstractly whose films were the continual development of longtime collaborators without being able to actually gauge their context or development. The festival’s reputation for being a very pleasant hang is justified (guests are put up at a hostel that’s a five-minute walk from the beach which, you know, is pretty nice). But attempts to defamiliarize my expectations and prepare for the future didn’t quite take. The thing I saw which landed most was coming from a much more familiar place — in fact, if I’d been on top of things, I could have seen the premiere performance of Zia Anger’s “My First Film” at Brooklyn’s Spectacle Theater. Instead, I caught up as Anger arrived in Miami direct on a redeye flight from Los Angeles, two years into performing the piece (more on that from the magazine archives here.)

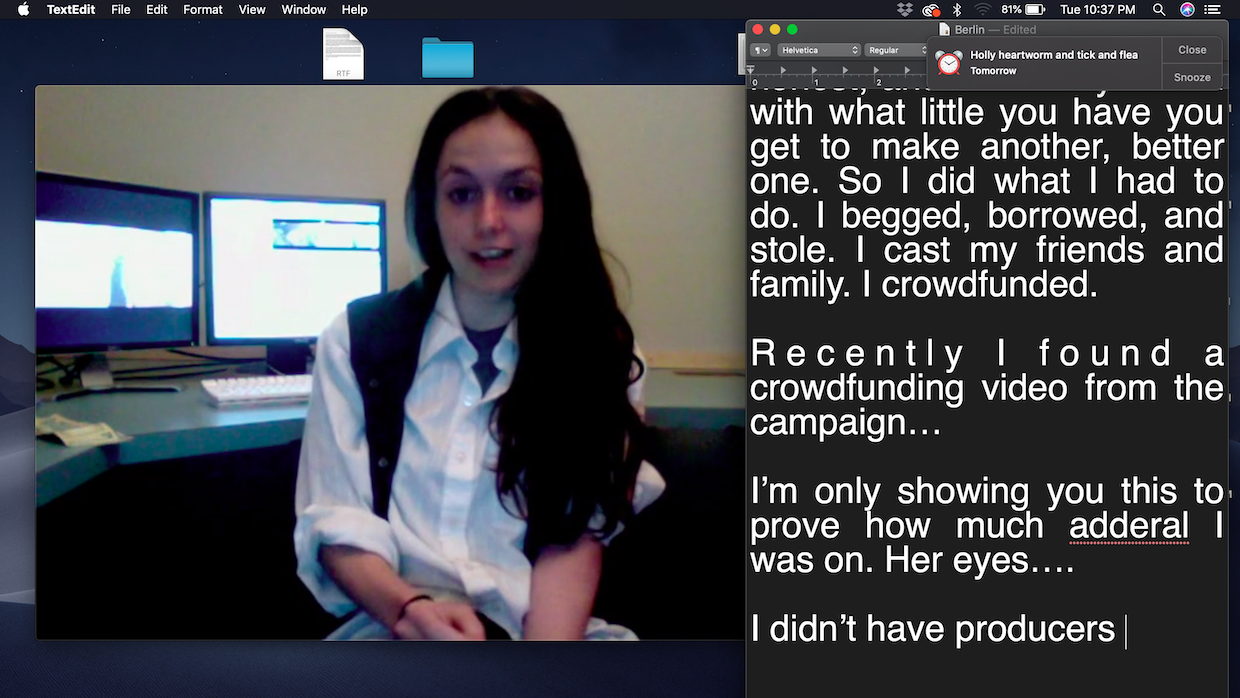

Anger’s performance, a kind of real-time desktop documentary, has been extensively written about by this point. The subject is a first film that was completed but doesn’t necessarily “exist,” a phantom feature that never got a festival premiere or made its way into the world. Anger, who tweaks her performance slightly with each rendition, played to a room overwhelmingly composed of known peers and industry types, making the note that these kinds of non-existent/suppressed “first films” are one of those open secrets never publicly discussed (which is true). Dissecting her Adderal-fueled crowdfunding campaign updates, digging up clueless emails from would-be commissioning bodies and skipping past all the worst parts of a movie she admits isn’t very good, Anger maintained her real-time performance while noting that she was barely hanging in there and that “you guys are really on one.”

It was a homecoming of sorts, ending with specific end-of-the-road thanks to the many colleagues along the way, in the room today, who’d helped bring this project about. It could have felt suffocatingly insular, but I found Anger’s frank, funny, productively granular breakdown of her experience — tied, as it inevitably would have to be, to the personal experiences she had along the way and often-traumatic memories baked into every piece of footage — moving and bracing. It was a perfect bookend to a film year that, for me, began with “Peter Parlow”‘s The Plagiarists, a movie about the anxiety of daring to make a movie when there might not be any justifiable reason to do so. Anger’s project is about different anxieties — not being able to make a film at all, for starters, plus a set of unavoidably gendered expectations and obstacles that don’t necessarily match the anxieties of the male subject/creators of Plagiarists — but it comes from at least partly the same larger worry: what it means to make a low-budget film for an audience so inherently self-limiting that reaching the larger cultural world will probably never happen (a possibility that’s inherently diminished the less cultural space non-“event” movies take up). But that work can still mean something, to at least a few people who need to see it, and there’s nothing wrong with looking those fears dead-on. That really did feel like the present moment to me.