Back to selection

Back to selection

Abandoned Goods: Artists and Filmmakers Jillian Mayer and Zia Anger Talk about Anger’s Film/Performance My First Film and the Meanings of Failure and Success

My First Film

My First Film With Zia Anger’s My First Film performance presented by Anger tomorrow at The Metrograph, here, from our Winter, 2019 print issue, is a conversation between Anger and filmmaker and artist Jillian Mayer, moderated by Sarah Salovaara, about all the various topics raised by the film, including how we measure success and failure in the independent world. Following the Metrograph performance, My First Film will play Sheffield Doc Fest June 7.

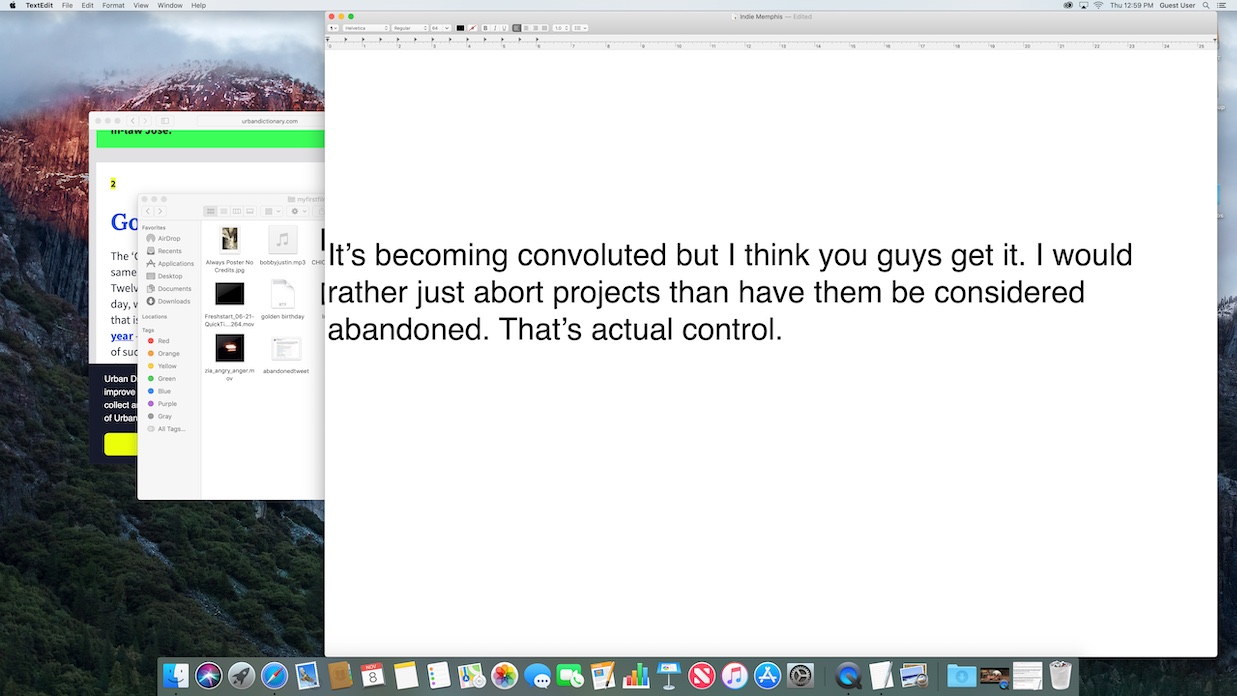

From 2010 to 2012, Zia Anger, whose short, I Remember Nothing, landed her on Filmmaker’s 25 New Faces of Film list in 2015, made a microbudget feature film in her hometown of Ithaca, New York, called Always All Ways, Anne Marie. Anger sent the feature to almost 50 festivals; it was rejected by all of them. In a two-channel performance entitled My First Film, Anger revisits that feature and other abandoned work with a live TextEdit commentary, relayed from the front of the audience, that reflects on her emotional histories and modes of process. A reclamation of a “failed” work and a rebuke of the independent film industry’s standards for success, My First Film plies the formal limits of a theatrical experience. After its festival premiere at Indie Memphis in November, Anger spoke in conversation with artist and filmmaker Jillian Mayer about the performance’s inception and each of their careers. For additional screening information, please visit the Memory site.

Mayer: The runtime of this performance is 70 minutes, so that kind of qualifies it as a feature, does it not?

Anger: Yeah, if performances are allowed to be qualified as features, but I don’t think if you tried to go onto my IMDb and enter it as a feature that it would work. The reason why this performance came to be is because I discovered what the IMDb qualifications are. In 2012, I made this feature, and when you make a feature and you want to get into film festivals, you log on to Withoutabox, and you enter all your information, and then you can apply to festivals. All these details are then also uploaded to IMDb. When you say, “The year it was finished was 2012,” or, “It’s going to be finished in September 2012, just in time for Sundance,” they enter that information, too, and they’ll write in red “pre-production” or “post-production” or whatever stage you’re in. What I discovered this year was that because this film I had made never got into any festivals, it still said it was in pre-production. So, I wrote IMDb through their generic help box and said, “Hey, delete this fucking movie, it’s not still in pre-production.” And rather than deleting all the movies I asked them to delete, it just wrote “abandoned” next to all of the movies [Always All Ways and an earlier short]. So, because I had never premiered them at a festival, films I had made were considered abandoned.

Mayer: That’s really interesting because your name now gets tied into this idea of someone who cannot complete something, and we all know that a person’s name and their likeness and their online self becomes a larger representative for their physical self. It’s kind of like this negative Yelp review within your burgeoning creative career. Or, it’s like getting an incomplete in school, but in that case the rest of the world doesn’t know about it.

Something interesting that you brought up is that one needs a film festival or a theatrical distributor to qualify a work as being finished. Therefore, a work is not completed until a separate business has qualified it as worthy of being experienced by an audience. I have projects that have never really gone the festival route, but they exist online and have larger audiences than probably certain works that are on IMDb.

Anger: What happened to me, which I say in the performance, is that I made this film, it didn’t go anywhere, and I felt really bad. What I don’t say in the performance is the career that everybody knows: I made a couple of short films, they got recognized, I got into Filmmaker’s 25 New Faces, and then people started to talk to me about making my “first feature.” Then I got into this really weird zone where all these really great filmmakers were telling me, “You should go and make a film for $20,000 with your friends as your first feature. Go make a mumblecore film.” I would try to tell people, “I did that already, and I didn’t get any recognition, and actually now I want to make something for $1 million.” And people would say, “Oh, you don’t want to go that route, you’ll never get a film made” — and that’s implicitly, “you, female filmmaker. You’ll never get your first film made for $1 million without getting sucked into the system and waiting a really long time.”

Mayer: If filmmaking’s a rich kid hobby — which I realized it is after I was already in too deep — maybe I would like to think it’s not gendered. I’d like to think it’s a class thing, almost. You won’t be able to do it if you are middle class or lower. And the people who want to help and support you, who want to see you do well, they always want to be part of the discovery train and [see you as] “virgin talent.” I understand the complexities surrounding the position you take: Do you become the wide-eyed, young millennial hopeful who says, “Yes, I would love to tap dance for you and make my first feature film again?” Or do you tell them, as nicely as possible, that you’ve already done that, but it was some type of process piece? What becomes the best avenue for a young filmmaker with ambition to be a young filmmaker with a project that is socially acceptable and receivable?

Anger: Right. And then when you tell people that you’ve already made the film, they kind of glare at you, like they are trying to remember if they’ve seen you at a film festival or if they’ve heard of your film. And then they realize that they haven’t. And then they just continue to tell you to go on and make something for $20,000. Did you ever make a feature?

Mayer: No. Lucas Leyva, my collaborative partner, and I made a short called Post-Modem that premiered at Sundance in 2013, and we have a large, expansive universe that we both thought this feature film should belong in, and we wrote too expensive of a piece. So, we tried to see it in different ways. We thought about it as an anthology, a Game of Thrones–type thing. We tried to see it broken up by characters, as some type of “world universe” with different apps and AR and VR. We still love it and believe in it, but now we see it as a three-act series of three features. So basically, all the different advice and guidance has us rethinking what we thought would be best to fit models and expectations of format.

A thing that stuck out to me so much about your performance was its successful presentation of failure. [There was the idea] that failure can become something else. Your failures now become a successful presentation that bring people through your journey from the inside out, and not only of the film’s creation but the presentation itself.

Anger: Right. When I conceptualized this performance, the implicit part of it was me thinking I want to tell everybody about [my experience] because it’s pretty fucking amusing, and because I don’t want anybody to go through this. I wish I had known [what I know now] over the last six years I’ve spent processing this failure. There are other people who’ve had similar experiences to me, and they will not talk about those experiences.

Mayer: Well, you have to become friends. Things are spoken about in quiet.

Anger: Right. But it’s this chicken-and-egg scenario, where you’re never going to meet those people who are going to tell you what happened to them until you get into the festival. But you need that information when you’re making your film to be able to get into a festival.

Mayer: Filmmaking and speculation seem to run parallel to each other, but also we are making magical, strange things that don’t need to exist. That’s something I think about, too: This is someone else’s money. In America, private money gets involved in making your creation. But in other countries, where there are larger funding pools of grant money from the government or other cultural groups, I wonder if it matters if things fail as much because it’s part of the infrastructure of their societies to support the art and artists.

In your performance, not only did you go through a couple of things that gave insight into your family, but you gave insight into [your thoughts] as a young filmmaker trying to make a film people would like and that was also a work of art that kind of synopsized your filmmaking influences. You also, which I thought was very beautiful, spoke about personal situations you were going through — trauma, both on and off set, [such as] someone getting very hurt in a car crash while you were filming, and that you felt responsible for. Again, I don’t want to make this too much of a gendered conversation, but I wonder sometimes if some of the responsibility and emotions that you were attributing to this project you felt in an enhanced way because as a female filmmaker you understood the hard march it is to push people through a project for little or no money.

Anger: In the performance, I talk about the checklist of the war stories that everybody has. Somebody gets hurt on set, or they get hurt off set, but it’s your fault. You do crowdfunding. [Laughs] Your parents cook food for [the crew]. You do all of these things that you’re supposed to do, and in the end everyone thinks it’s worth it because the film sees the light of day.

Mayer: Or, even better, it wins something. It was worth all those horrible things.

Anger: Right. But what happens when you’ve done all of this and it doesn’t go anywhere?

Mayer: Well, then it’s a theater piece. You sort of have done the most successful thing with all this material, to make it worth it, don’t you think?

Anger: Well, the first time I performed it at Spectacle I was really hungover, and I hadn’t invited any friends to come because I was so nervous about what this would be. But halfway through the performance, where there were about 15 people, I could feel this energy. They were laughing, you could hear people sniffling, and people were yelling and cheering. And at other times, they were really quiet. This immense rush came over me that I have never felt in a theater before. When you think about your film premiering at a really big festival, which is the dream I had for so many years, I always thought I would have that feeling wash over me, and it never did. At a certain point, I acknowledged I would have never have that feeling because this film wasn’t a success. It wasn’t a good film and that’s why it didn’t get programmed. And so then the experience of actually being in a theater and having this energy wash over me and this crowd react to this thing in the way that I had always wanted them to was just the absolute ultimate…. I don’t even know the words for it.

Mayer: There’s this point in the presentation that I found really touching, where you type, “You can’t see it right now, but I’m crying.” And the audience whimpers. But it doesn’t feel manipulative because every time you hit a sincere moment you kind of laugh your way out of it. And not in a fake humble way or an insincere way, but in the way of a person who is trying to reconcile and keep going on and keep making work, even though the project has faced some challenges.

Anger: What’s interesting about it being live is that I actually was crying. I’ve cried at different points when I’ve performed this, but at that moment, I said, “I’m crying” because I had finished screening or scrubbing through this feature, and it was the first festival I’ve ever showed it at. Maybe if I do it at more festivals I’ll cry, but I kind of doubt it. In the same way that you premiere your first feature at a festival and you cry and then you kind of get used to it — you get used to being on the road all the time and giving the same old awards speech or whatever.

Mayer: Whatever those losers do. [Laughs]

Anger: [Laughs] You ask, “Was it manipulative?” What’s really cool about being able to live-edit while I’m up there is being able to realize when I am being manipulative. I look at how I use language, how I’m relating to the people around me, and how I’m telling them this story, and I practice being the kind of filmmaker I want to be. I think that for a really long time I resisted calling myself a filmmaker; I was somebody who made films. And since doing this performance, for the first time I’ve been able to be like, “Oh, I guess I’m just an artist.”

Mayer: I was about to say, what do you call yourself?

Anger: Well, I always like to just tell somebody what my day job is. That’s always the most fun. People say, “What do you do?” And I say, “Oh, I just greet people at a fancy inn. I’m a door person.”

Mayer: I generally say that I’m an artist and filmmaker, and that lets me pivot into a different kind of conversation because some say, “What kind of films?” or “What kind of art?” And then it’s kind of whatever I want it to be at that moment. I used to be so shy or apprehensive to call myself an artist until I was socially accepted as an artist. I made art, or I made objects, or whatever, and people knew about them. But until I was socially accepted as [an artist], I had a lot of shyness about calling myself that. Even something as silly as getting [a work] framed — I would think, “How do I know it’s done?” The idea of investing money in declaring it done by encasing it in some kind of preservative material or archive freaked me out. Some people don’t know I make films and some people don’t know I make sculptures, which for me is a more fun place to be in. You can be as diverse as whatever thing you’re working on that week.

I think ultimately I’m just interested in communication. You can communicate with a large group of people — we’ll call them an audience — and whichever way you reach them is the way that gets considered when thinking about a particular topic or idea. A film audience knows they’ll go and sit somewhere for a while and receive information that will come to them in a multitude of ways: through audio, visually, probably a storyline of some sort, editing — all ways a filmmaker presents and works with propaganda to push an idea upon them. So filmmakers give a lot of information to the viewer. Something that’s always attracted me to the art-making process was this reductive approach where I have a larger, complicated idea, and I’m going to spend all this time thinking about it, and I’m going to produce one or two objects that essentially symbolically illustrate this idea or even challenge it.

So, as your work has gone in a circle, my work has as well. When I work on a film, the thing I’m most dying to do is make a huge mess, to work with paint and clay and gook. It’s really just trying to let ourselves make what we need to make, and let the work become what it needs to be.