Back to selection

Back to selection

“I Think the Public Deserves More Transparency”: Brian Knappenberger on His Horrifying Netflix Docu-Series, The Trials of Gabriel Fernandez

The Trials of Gabriel Fernandez

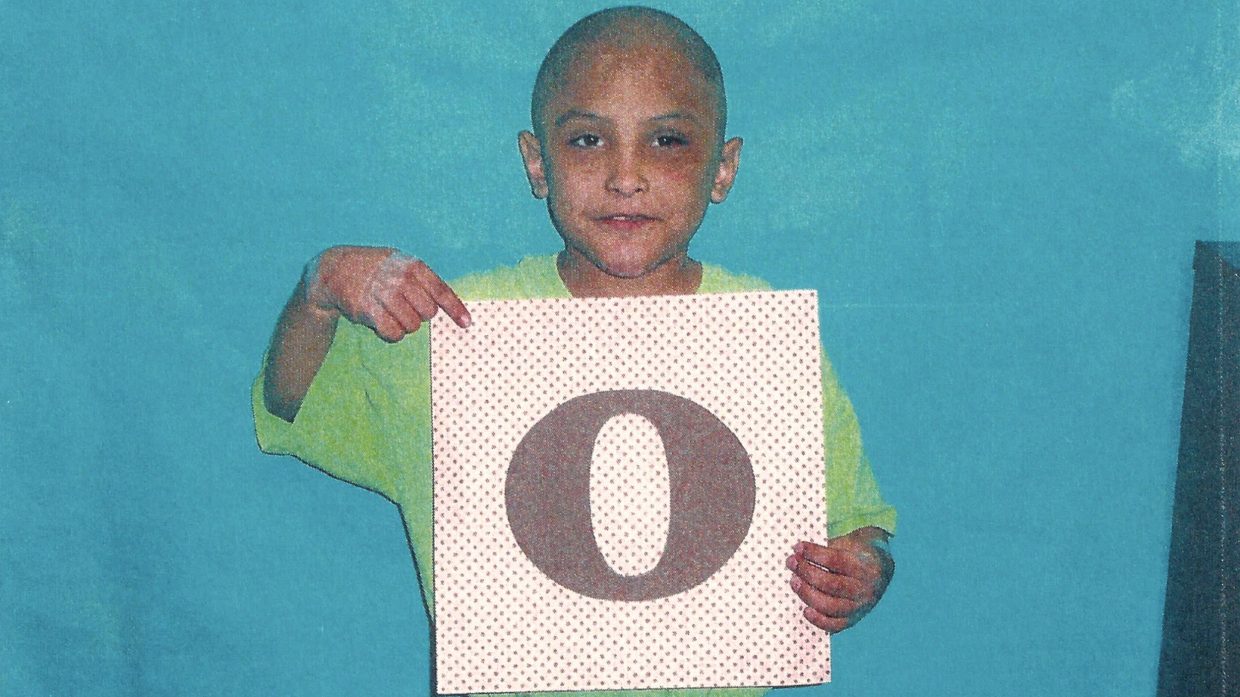

The Trials of Gabriel Fernandez The Trials of Gabriel Fernandez is a six-part Netflix docu-series from Brian Knappenberger (Nobody Speak: Trials of the Free Press) that delves into one of the most horrific crimes to hit Los Angeles headlines in recent years — the death of eight-year-old Gabriel Fernandez at the hands of his mother and her boyfriend after years of physical torture and emotional abuse. Taking as its starting point the courtroom drama of death penalty defendant Isauro Aguirre (after one too many outbursts from Gabriel’s mom Pearl Fernandez the accused murderers are ultimately tried separately), the series soon becomes something else entirely — a Kafka-esque saga of systemic culpability ensnaring everyone from Board of Supervisors politicos to overworked Department of Children and Family Services social workers (four of whom found themselves facing unprecedented criminal charges of their own). In other words, the sprawling scope of the story practically requires the docu-series treatment in order to do justice to Gabriel’s tragic case.

Filmmaker caught up with the busy director, in production on his latest, a few days before The Trials of Gabriel Fernandez‘s February 26th Netflix debut.

Filmmaker: So how did you get involved in this project? Was Netflix onboard from the start?

Knappenberger: Just as the trial of Isauro Aguirre was beginning, we were talking with investigative reporter Garrett Therolf about his breaking LA Times story about Gabriel Fernandez. Soon after, Presiding Judge George Lomeli gave us permission to bring cameras into the courtroom. The first few days were jaw-dropping. The room was full of raw emotion. We recorded testimony from career first responders who all said the case had stayed with them like no other. Around then Netflix came onboard as well.

Once we scratched the surface, though, it was clear the story went far beyond the death penalty trial of Isauro Aguirre. A large number of systemic issues played into what happened to Gabriel: social workers were charged criminally, third party contractors played a role, and a lot was revealed when the whistleblower came forward to paint a much bigger picture of what had happened.

Filmmaker: In what ways was the docu-series production process similar and/or different from creating a feature-length film?

Knappenberger: I love the multi-part documentary series. I really think it is one of the highest levels of the craft right now. It really is an amazing form, challenging in all the right ways, and I’m so glad that audiences are responding to it. For a filmmaker, if you can find the overall arc of a multi-part series that pulls audiences in, then you get the opportunity to explore all sorts of issues that you just couldn’t in a feature film.

Filmmaker: How did you go about convincing family members to open up during such a nightmarish time in their lives?

Knappenberger: The real answer to this is time. We were in the courtroom every day of the Aguirre trial and sentencing, and at most of the hearings of Pearl Fernandez and the social workers as well. Over the course of nearly two years people opened up to us, and we ended up really with extraordinary access.

Filmmaker: I read that you were unable to get the Board of Supervisors or the director of the Los Angeles Department of Children and Family Services to participate in the series. Did anyone give you a reason, or was this just a blanket refusal on everyone’s part?

Knappenberger: We asked them to be a part of this for nearly a year and a half. At first they said that since current DCFS Director Bobby Cagle wasn’t director when Gabriel died, he wouldn’t do an interview. Cagle seemed to be in a perfect position to answer questions about how things had changed since then, and how they were addressing the problems brought up by Gabriel’s case. Unfortunately their excuse broke down further when, during filming, there were a series of fatalities in rapid succession in the Antelope Valley that echoed what had happened to Gabriel down to specific details. DCFS and Cagle refused to talk about those as well, even though those were very much under his watch.

It is disappointing that Cagle wouldn’t interview with us. He is a product of the foster care system himself, and I genuinely believe he could have given us, and the public, some real insight on a very large platform. Past directors were more transparent, even when there were problems. (Former Director Phillip Browning did talk to us.) Unfortunately, I think too often the instinct within LA County is to resort to secrecy, as someone says in our series, to “protect the institution at all costs.” I don’t think secrecy serves the public, solves problems, or even does justice to the amazing, dedicated people currently working within the system as social workers. It is a big agency that touches a lot of lives. I think the public deserves more transparency.

Filmmaker: The role of journalism is key not only in this series, but in much of your work. So what compels you to return time and again to this subject?

Knappenberger: I’m worried about local journalism. It seems like there isn’t a week that goes by when we don’t hear about an amazing local newspaper around the county shutting down. Apparently subscriptions are up at national news organizations like The New York Times and The Washington Post, but so much happens at the local level that is critical to people’s lives. As a character in a Stoppard play once said, “People do terrible things to each other, but it’s worse in places where everybody is kept in the dark.”